As part of the training course to become a French curator, you are expected to do a placement of seven weeks in a foreign country. This helps not only to be able to speak a foreign language, but also to discover other methods and practices of work.

Personally, I was attracted by British history and culture, so I asked to come to The National Archives in Kew. My request was accepted, and I have been here since 15 February.

As an archivist, the purpose of this placement is for me to learn about the working of the entire archiving chain at The National Archives: the transfer of records, cataloguing, storage, conservation, communication to the readers. And of course I have to discover the role of the archivist in this work, for instance how they advise readers. The Institut national du patrimoine (INP) 1 has already taught me a lot about those methods. I have even mastered a part of this knowledge because of my former professional experience and the competitive examination you have to pass before entering at the INP. But mostly it was about the French methods.

And more than anything, it is much more instructive to learn on the ground than sitting at a desk or by reading books.

Image of The Galerie Colbert in Paris, headquarter of the French Institut national du patrimoine (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

My day-to-day work is very varied. My supervisors have given me several tasks. For instance, I have helped to catalogue part of the private Foreign Office correspondence exchanged with the British embassies all over the world around the First World War. This is a rewarding experience when you want to learn more about the main foreign policy issues of the time and to be in contact with the writings of the big names of history. I also reviewed the catalogue of the Paris Peace Conference Acts (1919). As they were mostly in French it has helped The National Archives and their staff, and from my side it was a way to plunge into the crucial diplomatic negotiations of this post-war period and to discover a part of their mysteries. That’s the win-win principle of a placement. Currently, I’m working to catalogue some very different archives: the reparations claims of French settlers of Santo-Domingo whose properties, including their slaves, were held in sequestration by the British occupation authorities between 1793 and 1798. 2

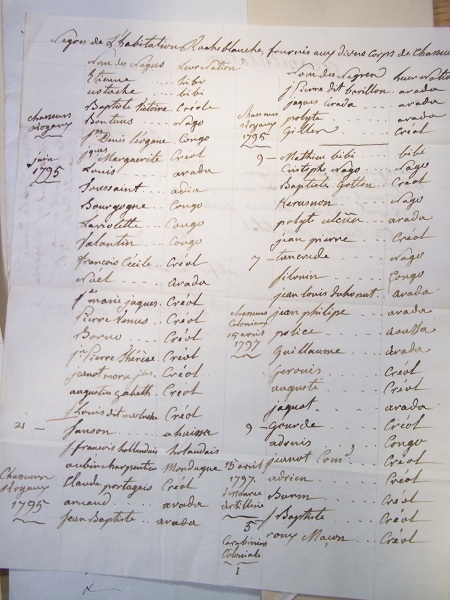

A list of slaves from a claim for a sequestered plantation at Saint-Domingue (documents currently being catalogued)

The cataloguing methods I have observed are quite different from the French practice: the literary form is favoured in the descriptions, and the entire catalogue of The National Archives is seen as a single instrument whereas the French archivists rather consider the inventory of a ‘fonds’ as a full work. The perspective is different: the British think of it from the user’s point of view, for whom the catalogue is effectively the single way to access to archives. The French use the point of view of the collections themselves, which are derived from completely different producers in very different times, and they don’t want these to be confused. It also explains The National Archives’ focus on the taxonomy, on the words which help the users to find records or archives; the French system is much interested in the administrative organisation and on the production context of the documents.

I also spent a large part of my time observing the entire functioning of The National Archives. I have attended working meetings, where I learned more about the current projects and issues in all areas of archives or academic services. I have also been able to meet individually some members of the staff who explained to me their roles. Similarly, The National Archives offers the possibility for trainees to attend ‘In Your Shoes’ sessions, where you can participate in the activities of other services in the building. For instance, I could discover the repositories and the department responsible for producing documents to the readers: a well-oiled machine. The staff were kind enough to show me the originals of some ‘masterpieces’ of the collections, like the letters from individuals signed ‘Jack the Ripper’ or King Henry VIII’s will. As an archivist and as an historian, I found this very exciting!

Of course, I have been especially able to follow the activities of the team where I am based, which deals with modern overseas records in the Advice and Records Knowledge department. I have observed the public service the staff provides in order to direct and help readers. That’s one point which has particularly drawn my attention: the work on the collection deals essentially with advising public on it. The direct mediation seems here to be considered as the best way to promote collections or improve knowledge around them, and the staff of The National Archives have developed a genuine expertise in this matter. Conversely, the French point of view gives a little more importance on indirect mediation: it perhaps explains that, in an equivalent team, French archivists would spend much more time on writing inventories and filing archives.

A claim for a sequestered plantation at Saint-Domingue, including a letter and a list of slaves (documents currently being catalogued)

French archivists are also considered less as collections curators and more as archival chain managers. This is not only because of a different division of labour, but also because of the definition of the archives itself. 3 Unhappily, all this means that they have often less time to spend with the public, which is a pity!

I would encourage all students, British or foreign, to do a placement at The National Archives. The working atmosphere is very good: the staff have listened to all my requests and taken time to explain me all the missions of The National Archives. And more than anything, you will learn a lot, meet some different people and work with fabulous collections.

Notes:

- 1. The National Institute for Cultural Heritage – the French state college which trains all the curators, whatever their specialities. ↩

- 2.The war pitted French Revolutionaries to British and Spanish troops who were also allied to some Royalist French settlers. ↩

- 3. In the United Kingdom, archives are considered as the selected records which have been preserved and transferred in some archive centres. In France archives are all the documents as soon as they have been produced, so archivists have an obligation to control and follow all the documentary production of public administrations. ↩

Interesting. What you describe about French archivists is not much different to way the Public Record Office (now The National Archives – TNA) used to spend literally years cataloguing records for publication and it was only academics who would turn up at the office until the 1970s, not surprising given that records were until 1959 often closed for 100 years and then you literally had to pay to see them. TNA does have an important role today as quite often departments do know about their own history, the Treasury is one that used to and staff would be sent (myself included) to do research at the Public Record Office and how to do it, but no more, alas. I would that if you get out one of the

T 108 (Treasury Subject Registers from the 1870s onwards to 1920) you will be amazed by what is listed there and in some cases the entries are as good as the files (T 1). One of the biggest shocks was when John Maynard Keynes who was working at the Treasury and who attended the Versailles Peace Treaty in 1919 resigned the next day over the requests for reparations from Germany and he could see what was going to happen, another World War.

I do, as TNA know, have issues over the taxonomy as they don’t always work, like putting cases of request for political asylum under ‘mental illness’ and the ‘Brain Drain’ (keeping people with big skills in the country with Government aid) are listed under ‘sewerage’.