For Lionel his sonne with theim to send

The duke his doughter of Melayn for to wed

Promysing then hym so to recommend

That of Itale the rule sholde all be led

By hym and his frendes of Italye bred[ref]The Chronicle of John Hardyng, ed. H. Ellis (London, 1812), pp.332-3[/ref]

- 19th century drawing of the bronze effigy of Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence on the tomb of his father Edward III, Westminster Abbey (source: Wikicommons)

- Image of a painting of Violante Visconti and her brother Gian Visconti, pre 1380 (source: Wikicommons)

The 15th century chronicler, John Hardyng, wrote these words in tribute to the little known marriage between Lionel, Duke of Clarence, the second eldest son of King Edward III, and the daughter of Galeazzo Visconti, Lord of Pavia and Duke of Milan in the late spring of 1368.

The marriage was part of a negotiated Anglo-Milanese alliance and the verse above goes so far as to proclaim the marriage as the foundation of future English royal rule in Italy.

This it was not, but Lionel’s match to Violante Visconti promised the English royal house an important stake in northern Italy and served to enhance Edward III’s broader diplomatic ambitions in western Europe.

Unfortunately the benefits that such a match offered, complete with extravagant wedding ceremony and Violante’s eye-wateringly large dowry of 100,000 florins (nearly £15,000 or almost £5.5 million in todays money), were dashed a few months later when Lionel suddenly and mysteriously died.

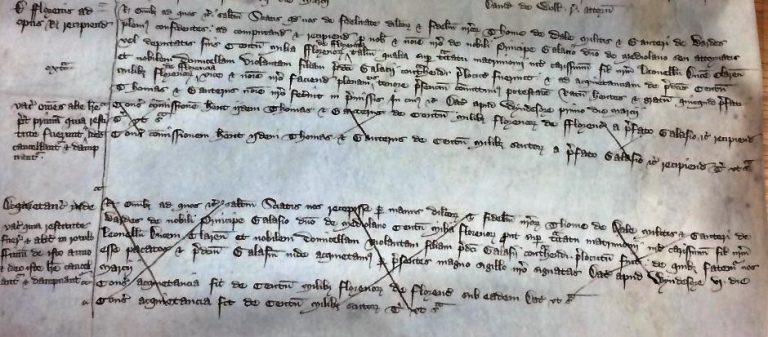

Entries in the Treaty rolls pertaining to collection of the dowry of 100,000 florins: the top entry indicates that Sir Thomas de Dale and Walter de Bardes were authorised to account and receive the dowry payment from Galeazzo, Lord of Milan, dated 1 and 6 March 1368. (catalogue reference: C 76/51 m.7)

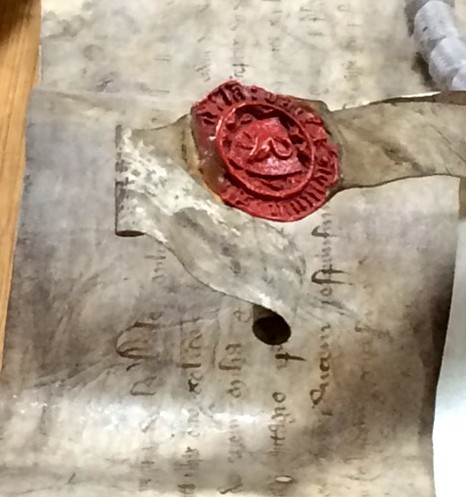

Receipt and seal of Thomas de Dale, attorney of Lionel Duke of Clarence for £56, 8 shillings, 11 pence granted by the king to Walter de Bardes in addition to 17,500 marcs (over £11,500 or approx. £4.2 million today) received from Galeazzo Lord of Milan for the marriage of the said Duke. Dated at London, 20 May 1368 (catalogue reference: E 42/233)

This unknown royal wedding in the hills of Piedmont could perhaps have come from the pages of either Shakespeare or Machiavelli.

So what happened?

The answer as to why this marriage took place in the first place is found in the failure of an important Anglo-Flemish marriage to occur.

Edward had secured the marriage of his fourth surviving son, Edmund of Langley, to the only daughter and heir of the count of Flanders Louis de Male. A much coveted diplomatic prize, it promised English control of a region with historic economic and political ties to England.

The marriage required a Papal dispensation because the two were related. Pope Urban V, who was concerned with further expansion of English royal power was reluctant to grant dispensation.

Therefore, Edward, wanting to ensure his hard won Flemish marital alliance was not snatched away, embarked on another scheme to ‘persuade’ the papacy to change its mind.

Enter the Visconti dukes of Milan, principal enemies of the Holy See, with whom the Milanese duke had fought bitter and frequent territorial wars.

An entry in the Patent rolls (C 66/274 m.35) on 20 July 1366, reveals that the Earl of Hereford and the distinguished Knight and royal emissary, Sir Nicholas Tamworth, were appointed to treaty with Galeazzo, for a marriage between either Lionel or his younger son Edmund and Galeazzo’s daughter, Violante.

Negotiations evidently proved fruitful as Galeazzo sent his own proctors to London, who put their seals to the articles of a treaty drawn up on 15 May 1367 (pictured below).

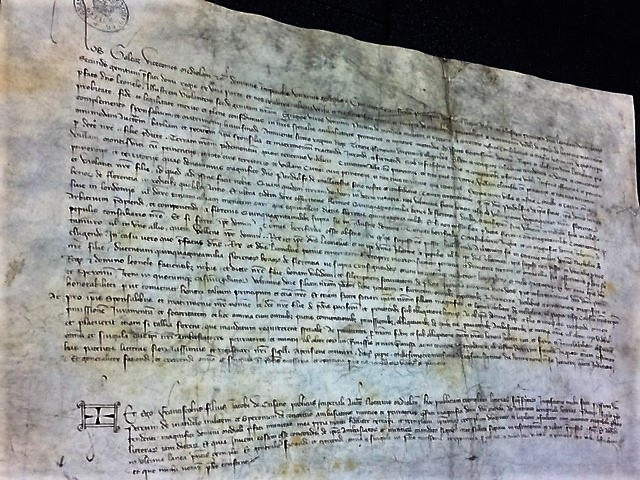

The appointing, by Galeazzo Visconti Duke of Milan, of Peter de Mandelo and Sperone de Concorezio as ambassadors to England to conclude a treaty of marriage between Lionel Duke of Clarence and Violante Visconti. Details of the generous dowry to be offered are provided including not only the enormous cash payment but also several towns in Piedmont including Alba and Cuneo to be offered to Galeazzo’s future son in law, dated 19 January 1367. (catalogue reference: E 30/240)

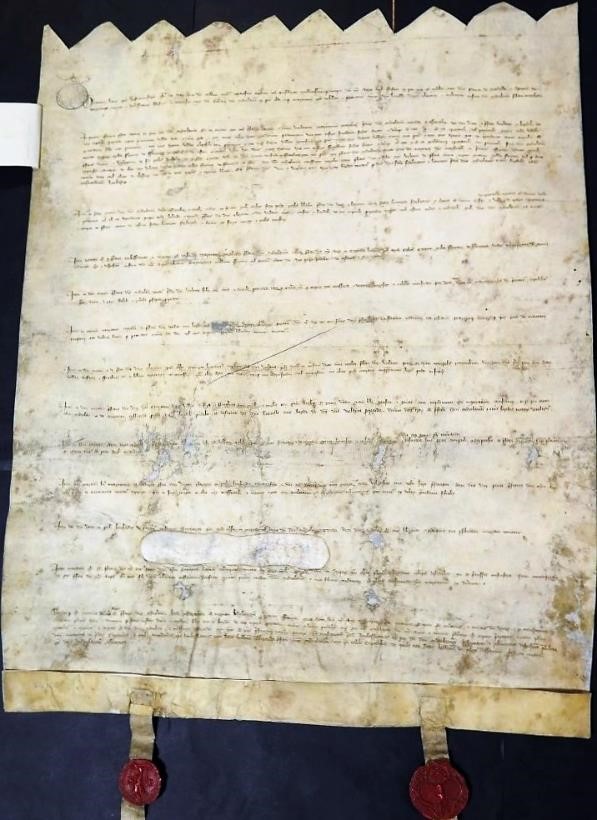

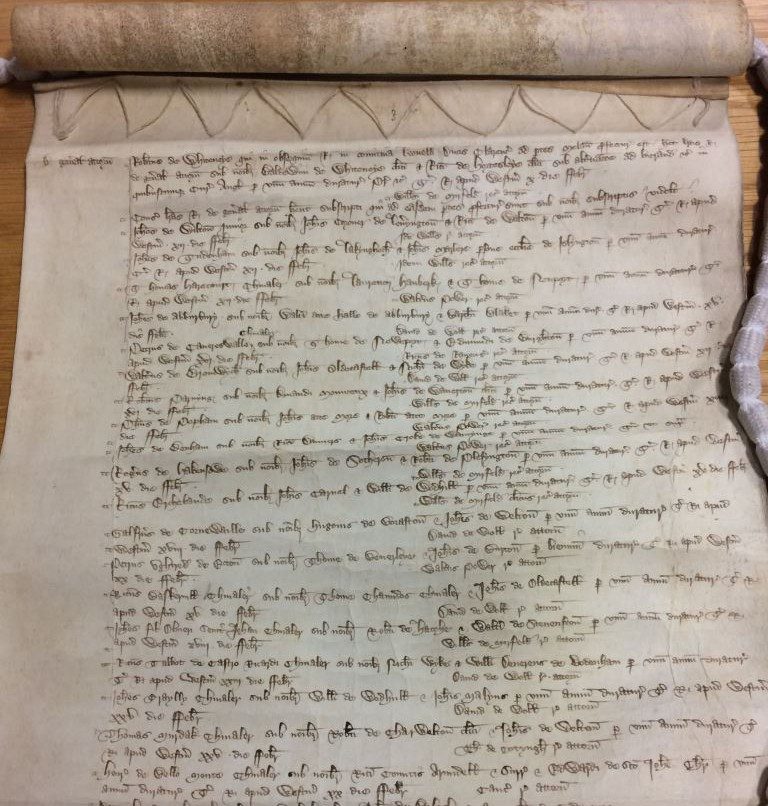

Articles of the Anglo-Milanese marriage treaty dated 15th May 1367 (catalogue reference: E 30/247)

Edward hoped that this diplomatic manoeuvre on its own or in tandem with military pressure on the Papal States in Italy might secure the longed for dispensation for the Flemish marriage.

Perhaps the threat alone of unleashing English mercenaries in the pay of the Visconti under mercenary captain, Sir John Hawkwood, would be sufficient. Hawkwood was arguably the most successful and formidable of English mercenaries to find service in 14th century Italy, earning both fortune and fame for his military prowess. He too was involved in the Anglo-Milanese marriage negotiations.

- Left hand seal on the treaty document of Milanese ambassador Sperone de Concorezio authorised by the duke of Milan to negotiate a treaty of marriage with Edward III (catalogue reference: E 30/247).

- Right hand seal on the treaty document of Milanese ambassador Peter de Mandelo authorised by the Duke of Milan to negotiate a treaty of marriage with Edward III (catalogue reference: E 30/247)

Meanwhile, the groom to be was ready to embark from his native shores in early April of 1368, travelling from Dover. An entry in the Exchequer Liberate rolls (E 359) confirms that he was accompanied by a large retinue of 457 prestigious English knights and squires and 1280 horses.

Shipping the Duke, his retinue and horses to Calais required a fleet of 52 vessels and was evidently not cheap, costing £173 6 shillings, 8 pence for passage, plus a further 106 shillings 8 pence in transportation costs for the horses.[ref]Published in Thomas Rymer, Foedera, Vol. VI, pp. 590-591[/ref]

Enrolments of general attorney appointed by Robert de Whitney and 25 other soldiers in the Duke of Clarence’s retinue accompanying him to Milan (catalogue reference: C 76/51 m.8)

For the groom and his entourage, the journey to Milan through France and northwest Italy was itself an extravagant foretaste of the plush wedding to come.

En route, the groom and his party received lavish hospitality from King Charles V of France and Count Amadeo VI of Savoy with the French King alleged to have bestowed gifts on Lionel and his followers that were worth 20,000 florins (almost £3000 or just over £1 million today)[ref]A.S. Cook, The Last Months of Chaucer’s Earliest Patron (New Haven, 1916), pp.38-39[/ref]

Lionel finally reached Milan on 27 May, his retinue now swollen since entering Italy with bands of English mercenaries connected to Sir John Hawkwood.

With the groomsman now present, the wedding was arranged a few days later in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore. It was probably performed beneath the church’s central door to enable throngs of Milanese citizens and nobility to witness the spectacle.

Such was the extravagance of both the celebratory 18-course banquet that followed and the gifts showered on the bride and groom, that individual courses and presents are recorded in the accounts of several chroniclers.

In one course alone a hare and young goat in chive or pickle sauce was served, accompanied by gifts of six great coursers with gilded saddles and trimmings emblazoned with the arms of Galeazzo and the Duke, six shields, lances and steel hats and other items! Exquisite gifts were even bestowed on seven of Lionel’s retainers including sliver gilded belts, jousting steeds and pieces of gold cloth.[ref]The courses and gifts described in several chronicle sources are summarised in Ibid, pp. 65-74.[/ref]

For all the pomp and grandeur of the wedding feast, it was not to be the fairytale ending for the happy couple, as barely four months later on 17 October 1368, Lionel died. It was thought by some contemporary commentators that he had overindulged in feasting and banqueting.

Lionel’s loyal deputy commander, Edward le Despenser, on the other hand concluded that his Lord had been maliciously poisoned by his Milanese hosts.

Despenser sought to avenge his master by refusing to surrender the towns and castles of Lionel’s dowry and rallying bands of English mercenary companies in northern Italy waged war on the Visconti house.

Although eventually reconciled to Galeazzo, there may be some truth to Despenser’s suspicions, but foul play if committed at all, was more likely to have been perpetrated by papal agents or other enemies of the Visconti lords.

Whatever the cause, Lionel’s untimely death unravelled Edward’s attempts to break the diplomatic deadlock with the Papacy. The count of Flanders, anxious to secure his daughter’s future, reluctantly entered negotiations with France.

The final decisive blow to Edward’s diplomatic strategy came on 19 June 1369 when Louis’ daughter Margaret was married to the younger brother of Charles V of France.

Things may have gone differently had Lionel lived and had the opportunity to prove his own martial and political reputation in northern Italy.

Yet the premature death of Edward III’s forgotten son should not detract from the devotion he evidently showed towards the prestige of England’s ruling house right up to his death. Certainly this at least qualifies him to occupy a more favourable place in history that he no doubt deserved.

Very interesting!

But I wonder how reliable “The Last Months of Chaucer’s Earliest Patron” by A.S. Cook is (Footnote 3). I may have to buy the book to find out ; )

Although Lionel’s trip through France took place in early 1368, a year prior to the breaking of the Treaty of Brétigny in 1369 (when the Hundred Years War resumed), one wonders about Charles V’s lavishing of gifts on the son of Edward III, allegedly, as you say, worth up to 20.000 florins. During the 1360s, much of Champagne and Burgundy and churches and monasteries in the newly-named Principality of Aquitaine, had been laid waste by the Great Companies, many of whose members were of English origin.