Like many French people of my generation, I’ve grown up amidst war stories – life under the Occupation, Resistance deeds and treason tales, arrests and escapes, deportation and rescue. At some point, having gone through Jorge Semprún‘s entire bibliography with the kind of morbid fascination that, consciously or not, grips us all when it comes to this period of history, I thought I would never be able to stomach another book on the concentration camps. Yet, in a decidedly anachronistic, out of context way, Kipling’s words ‘lest we forget’ now spring to mind.

70 years ago, on 27 January 1945, the Auschwitz concentration camp complex was liberated by the Soviet 60th Army of the First Ukrainian Front. What they found there was beyond words. Lieutenant-Colonel Johnston, who commanded the 32nd Casualty Clearing Section and arrived at Bergen-Belsen in April 1945, gave a statement with which the Russian troops would probably have agreed: ‘it is quite impossible to give any adequate description on paper of the atrocious, horrible, and utterly inhuman conditions of affairs’.

At first, very little information filtered out. A Foreign Office official noted on 10 February: ‘we have not yet had any kind of information officially (…) about what may have been found as a result of the Russian capture of Oswiecim, the extermination camp in Upper Silesia’. A Soviet Extraordinary State Commission was appointed to investigate, and the report it submitted in May 1945, combined with statements from survivors and interrogated Germans, enabled the world to realise the full extent of the atrocities that had been perpetrated in the camp.

Its conclusion was blunt: ‘As regards the elaborate manner, technical organisation, mass scale and cruelty of extermination of people, the Oswiecim camp far surpasses all hitherto known German ‘Death Camps”. A former prisoner reported having once heard the Camp Commandant claim: ‘our system is so terrible that no man in this world will believe it to be possible – even should a Jew succeed in escaping from Auschwitz and telling the world all he saw. The world will brand him a fantastic liar and nobody will believe him’. It is indeed impossible to read these documents, page after page of statements and reports, without shuddering or wanting to stop. We all know the horror stories, but I am going to tell them again, albeit very briefly, because after having ploughed through about 30 boxes of documents, well, I need to share them.

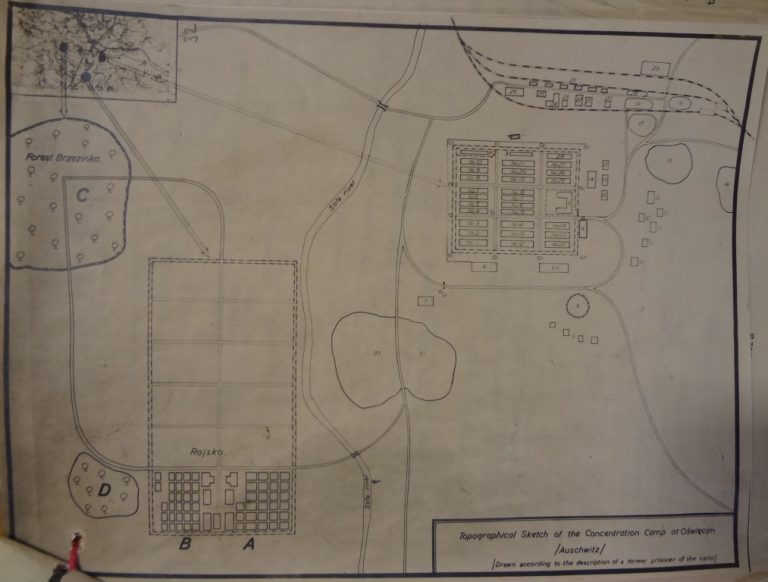

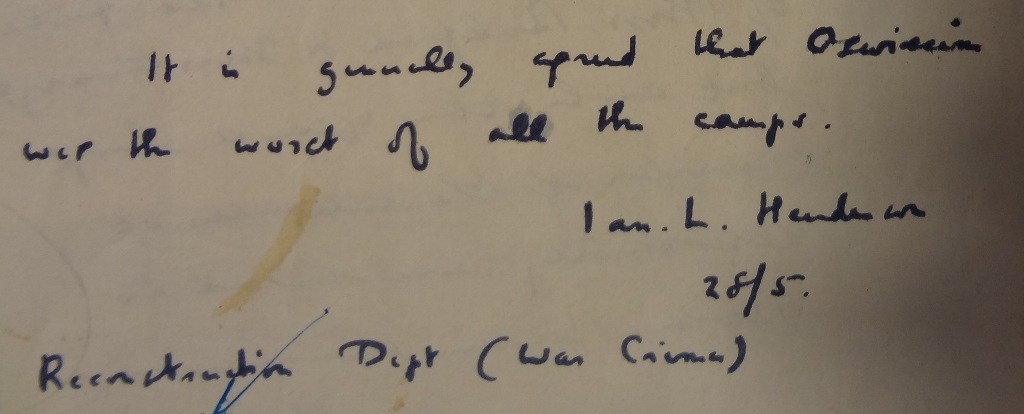

Described by the Russian newspaper Pravda, on 7 May 1945, as ‘a conveyor-belt of death’, and by the Foreign Office as ‘the worst of all camps’, Auschwitz was a network of more than 40 camps near the small town of Oświęcim, in Upper Silesia (the part of southern Poland which had been invaded by Germany in September 1939).

Auschwitz I, the Stammlager, was built in 1940, to hold Polish prisoners. Auschwitz II-Birkenau, which was to become the very heart of the ‘final solution’, was built in 1941 to ease congestion at the main camp, with its first gas chamber operational by March 1942. Auschwitz III-Monowitz was constructed in 1942, to house those slave-workers assigned to the I.G. Farben synthetic oil and rubber plant. Together, they formed a most efficient death factory which consumed its victims in a few hours and put the survivors though hell.

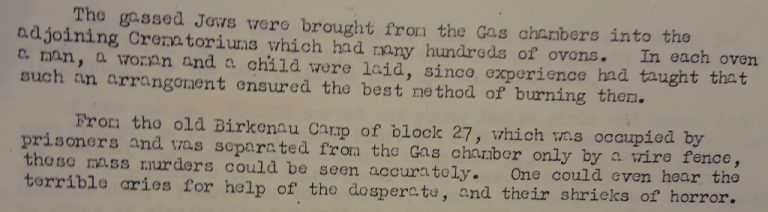

When the prisoners arrived, already exhausted by a long train journey in cattle wagons, and while they were facing an arch bearing what has to be the most cynically sinister slogan ever thought of, ‘Arbeit macht frei’, they went through their first selection process. Those who were deemed fit enough to work were taken to the barracks; the others, mainly women, children and elderly people, were marched or driven away to be ‘sonderbehandelt’ – specially treated. Told they had to be disinfected, they were given a bar of soap and a towel and herded into what looked like a large shower room. According to witnesses, the doors were locked, crystals of Zyklon B thrown into the room through apertures which could be hermetically sealed, and they all died in less than twenty minutes.

Once the air had been cleared, the Sonderkommando’s work could begin. These prisoners, who were replaced (read: executed) every three months or so, had to search the bodies to retrieve any valuable item and extract all the gold teeth they could find. The bodies were then dragged to the nearest crematorium and disposed of.

It has been estimated that at least 1.1 million prisoners died at Auschwitz; most of them were Jewish, but prisoners included Jehovah Witnesses, homosexuals, Poles, Soviets, Romani, and a dozen nationalities. While the people ‘selected’ upon arrival do not appear on the concentration camp returns, they are frightfully clear: dozens of thousands of people were killed each month. Those who were not gassed were executed, or died of exhaustion, starvation, diseases or medical experiments.

Animated by perverted ideals fuelled by racial biology, the Nazis had a dangerous interest in reproduction. They wanted to facilitate the reproduction of the ‘Master Race’ as well as stall that of the ‘inferior races’. A considerable number of medical experiments were carried out at Auschwitz, using prisoners, mainly women, as human guinea-pigs. Among those Nazi doctors, the most famous probably are Josef Mengele and Carl Clauberg. Mengele had a very special interest in twins, but they both performed artificial insemination, removal of the ovaries, removal of the breasts, sterilisation by means of electricity, various experimental injections…

With an impressive amount of cynicism, a former prisoner reported: ‘A scientist like Professor Clauberg, conscious of his responsibilities to suffering mankind, could not leave the cancer problem untackled. By a skilful operation, he incised the wombs of healthy young women and implanted cancer cells and cancer tissues into them. Then, patient as German scientists are known to be, he waited weeks and weeks before he removed the whole womb to see what had happened to his cancer cells.’ Just for the record, neither Clauberg nor Mengele were executed after the war. Clauberg was sentenced to 25 years in a Soviet prison, but benefited from a prisoners of war exchange between West Germany and the Soviet Union, and was released after 7 years; arrested again in 1955, he died before his trial started. Briefly detained by the Americans, Mengele escaped to South America and was never caught; he drowned off the Brazilian coast in 1979.

The discoveries made by the Red Army in Auschwitz were somewhat limited. As the Russian were approaching, the Germans started destroying all their records and covering up the traces of their activities. On 20 January 1945, they blew up crematoria II and III. On 23 January they burnt down Kanada II, the warehouse in which the prisoners’ personal effects were stored; on 26 January, they blew up crematorium V, which was fully functioning. The Germans also evacuated the camp. On 17 and 18 January, about 58,000 prisoners were marched away westwards, in ice cold weather; those who were slowing down the rest of the convoy were shot, others just collapsed. By all accounts, the roads were lined with the bodies of those who could not endure the 55-kilometer march to the camps of Gleiwitz or Loslau. About 18,000 prisoners died during these death marches.

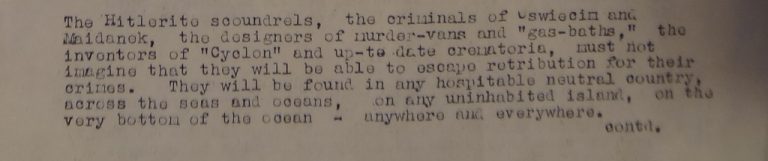

When the 60th Army entered Auschwitz I and II in the afternoon of the 27 January, they found about 7,000 prisoners who had been too weak to leave. The Soviets had already liberated Majdanek in July 1944, so Nazi atrocities were not entirely new; with the liberation of Auschwitz, however, they took a whole new dimension which triggered unprecedented hatred and desire for revenge and justice. On 7 May, the editorial of Russian newspaper Pravda summed up the feelings of the public opinion quite well: ‘The Hitlerite scoundrels, the criminals of Oswiecim and Maidanek, the designers of murder-vans and ‘gas-baths’, the inventors of ‘Cyclon’ and up-to-date crematoria, must not imagine that they will be able to escape retribution for their crimes. They will be found in any hospitable neutral country, across the seas and oceans, on any uninhabited island, on the very bottom of the ocean – anywhere and everywhere.’

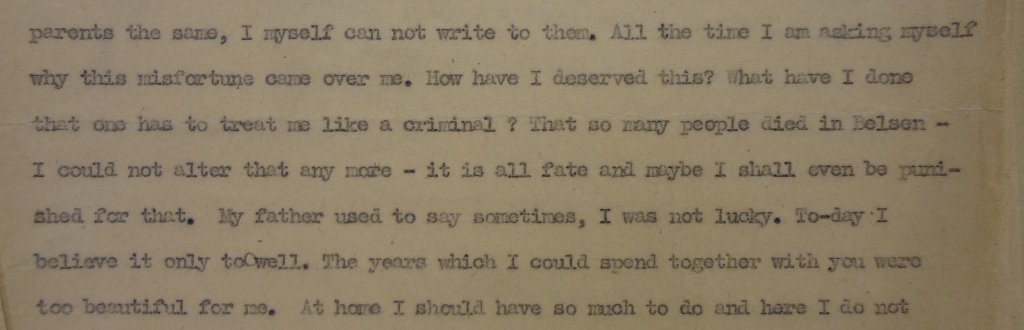

While some of the Auschwitz leaders, such as Mengele and Clauberg, were never caught or released, most of them were captured, tried and executed. Most of them were also in denial and refused to take responsibility. SS-Hauptsturmführer Josef Kramer, better known as ‘the Beast of Belsen’, was in charge of the gas chambers in Auschwitz. Tried by a British military court at Lüneburg in 1945, during the Belsen Trials, he wrote to his wife: ‘all the time I am asking myself why this misfortune came over me. How have I deserved this? What have I done that one has to treat me like a criminal?’

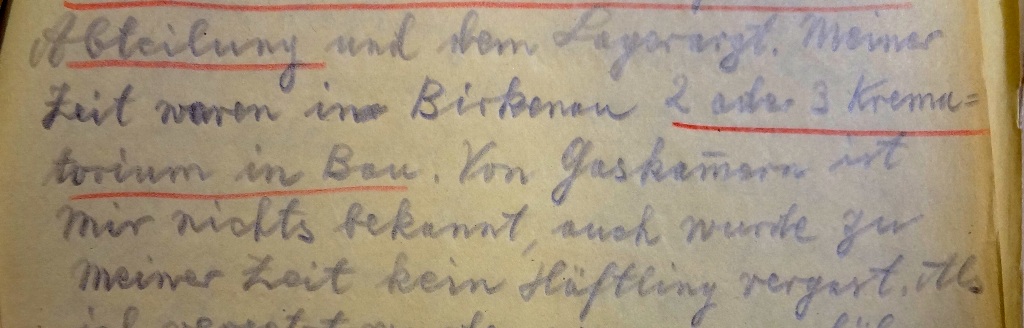

In his statement he blamed Himmler, Pohl and Glücks, who were at the head of the concentration camp system, and added ‘if Hitler knew what was going on, the responsibility of all this falls on him, but I do not think that he knew’. Sentenced to death, he was hanged on 13 December 1945. SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Aumeier, deputy Commandant of Auschwitz, was arrested in June 1945. According to his interrogator, he did not ‘conform to the standards set by the Third Reich leaders for the Master Race. Undersized, ugly and unintelligent, Aumeier has resigned himself to being brought to account as a member of the Auschwitz staff for the bestialities perpetrated there and to take the punishment due to him.’ Aumeier, however, was not quite prepared to take responsibility for all these atrocities and, although he recognised crematoria were under construction in Birkenau when he served there, he denied knowledge of the gas chambers: ‘I don’t know anything about gas chambers,’ he claimed, ‘and during my time [in Auschwitz] no prisoner was gassed’. Sentenced to death, he was hanged on 28 January 1948.

SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss, Commandant of Auschwitz, eluded capture for a while, and was finally arrested by the British 92nd Field Security Section. He was handed over to the Poles, tried, sentenced to death and hanged on 16 April 1947 at Auschwitz, a few yards from the former crematorium.

70 years after the liberation, the Allies’ decision not to bomb the camps, and Auschwitz in particular, remains controversial. How much did they know? If, as evidence tends to show, they knew exactly what was happening, why didn’t they put an end to the massacre by bombing the gas chambers or the railways? How could the analysts interpreting the aerial photographs of the I.G. Farben factory miss the convoys, the prisoners, the smoke coming out of the crematoria?

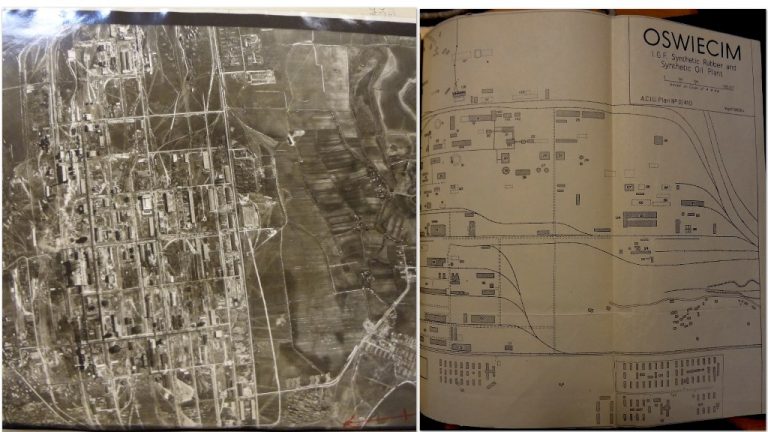

The IG Farben factory and Auschwitz concentration camp, 4 April 1994. Catalogue reference: AIR 29/332

Today, however, is a day for solemn remembrance rather than historical controversies. My great-grandmother frequently talked about her time as a political prisoner at Ravensbrück; my great-grandfather, on the other hand, always said that he had done what he had done so that we never had to experience the same horrors, and very rarely mentioned the war. With all due respect, I have to disagree. If we want to make sure that it never happens again, we have to remember. In the words of Karel Sperber, a Czech doctor interned at Auschwitz, ‘to those who forgive and forget too quickly I dedicate these lines.’

[…] today’s blog post, records expert Dr Juliette Desplat examines records which show the horror and inhumanity of […]

I cried when I read this. The picture of the gate these souls went through hit me like a bolt of lightening in the chest, something I have not experienced before. (I’m 60) Thank you for this article.

I am looking for the name of the first English woman officer to enter Auschwitz after liberation. She may have been with the 60th army.

The date you give is the third date I have seen for Aumeier [Aumeyer -wrongly spelt) execution (Wiki and Jewish virtual Library) but this is the best authority so I will say he was executed on the 28 Jan 1948.

Question of Allies Bombing of Auschwitz. I disagree it was viable for the western allies. These are my points:

Knowledge of Auschwitz, with mixed views on it’s authenticity was indeed present in western high Allied counsels. But there was no precision bombing in the 1940s (except for Mosquito air craft but they had limited range). For example rail lines in Normandy in advance of the invasion were destroyed by resistance members because aerial bombing would miss most of the time or be in-effective. Same with buildings to a lesser degree. Besides Auschwitz was at the limit of fuel kilometers for bombers, it was very high risk for the crew. The question itself, as shaped here, is as often as not phrased for the western Allies. The Soviets close by could have bombed the necessary targets but did not. As the above shows Majdanek had been liberated by Soviets in July 1944 so the Soviet high command had full awareness of what the labour/death camps beheld. The question has to be posed to them first not the western Allies.