A library’s worth of comment and analysis has built up on the character of Fidel Castro since he seized power in Cuba on 1 January 1959, and a couple of extra shelves’ worth have been added since his death on 25 November this year. Assessments of the beliefs and personality of this Cold War titan and his five decades as Cuban leader tend to have been skewed either by idealistic hopes, intense bitterness or political dogma: a cruel and tyrannical megalomaniac on the one hand, a benevolent dictator and bastion of oppressed peoples on the other. Such bias is, of course, supposed to be absent in the assessments made by diplomats.

The UK has had a diplomatic mission in Cuba for over 100 years and, unlike the US, an embassy in Havana throughout the years since Castro’s 1959 revolution (the US closed its embassy in 1961 and did not reopen it until 2015). The British diplomatic view of Castro, much of it recorded in Foreign Office documents held at The National Archives, has been relatively measured and considered, providing a valuable take on the man, though one, of course, not entirely free of bias.

It was a view that began to be formed very gradually during the 1950s, pieced together and initially reliant largely on rumour and second-hand reports. These were years in which Castro was a somewhat mysterious figure, operating underground, at first as a political dissident and towards the end of the decade as a guerrilla leader. He was described on more than one occasion in British diplomatic correspondence as the ‘Cuban Robin Hood’.

From this comparative obscurity Castro exploded onto the international stage in 1959 as the triumphant figurehead of the Cuban Revolution. By 1963, now a globally renowned figure, just ten years after his name had first popped up in British Embassy reports from Havana, he was the subject of a 2600-word profile compiled by the ex-British Ambassador for a Foreign Office now scrutinising his every move.

Dramatic debut

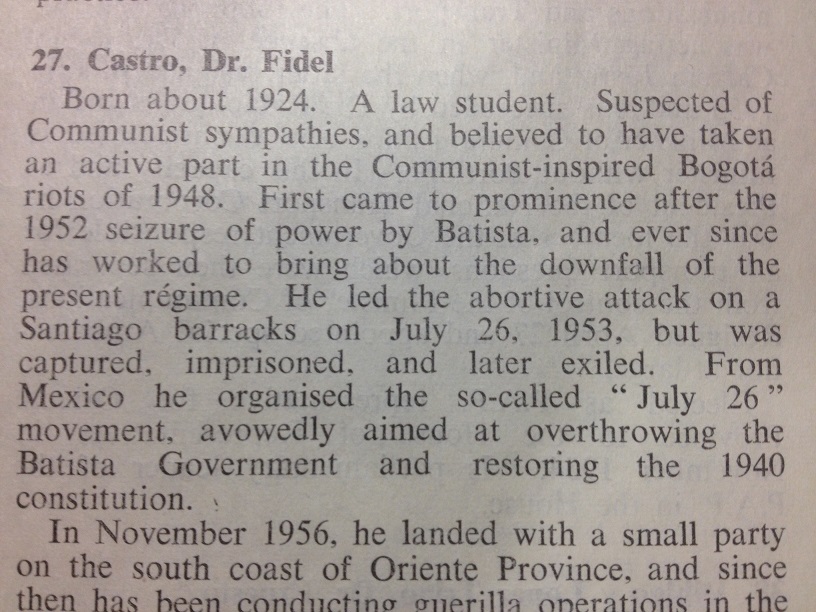

The first appearance of Castro on the British diplomatic radar seems to have been in July 1953 when he attempted an audacious seizure of power with a band of some 200 rebels at the Moncada Barracks in Santiago, Cuba’s second city. This attack against the military of Fulgencio Batista, the then dictatorial Cuban President who himself had seized power in 1952 was an outright failure, described by the British Ambassador in Havana, Adrian Holman, several days afterwards, as ‘another hair-brained or suicide escapade[…]probably engineered without any coordination or foresight by a number of hot-heads in the opposition parties[…]’ (FO 371/103376).

The ‘hair brained’ architects of the attack were not known to the British at the time of the attack, but by November 16 1953, when Holman reported on the subsequent trials of the captured rebels, he was able to name names:

Fidel Castro under arrest after the attack on the Moncada Barracks (image from Wikimedia Commons)

‘On 7th of October 28 of the accused were condemned to various terms of imprisonment[…]. A week later the leader of the revolt, Fidel Castro, whose trial had been delayed by his illness, was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment[…]. The trial[…]failed to unearth any direct evidence of[…]Communist complicity’ (FO 371/103376).

Prior to and during the 1950s, the Communist Party in Cuba, in its various guises after it was outlawed by Batista, did not count Castro among its members. In 1952 he had run for office as part of the more moderate, left-leaning Ortodoxo Party but abandoned mainstream politics, frustrated and disillusioned, after Batista took control of the country in a coup d’état that year.

Following a year and a half of incarceration, Castro reappears briefly in several British diplomatic reports towards the end of 1956 as rumours circulate that he and others are planning to assassinate Batista and launch a coup d’etat in Cuba from Mexico, where he was exiled following his early release from prison. British interest in him at this time, however, was still minimal, to the extent that comments made by the Foreign Office in response to the first of these reports, sent by the British Embassy in Mexico, include the judgement that ‘We have no information about any of the participants, who I suspect are just a bunch of rogues with too little to do’ (FO 371/120116).

Cuban Robin Hood

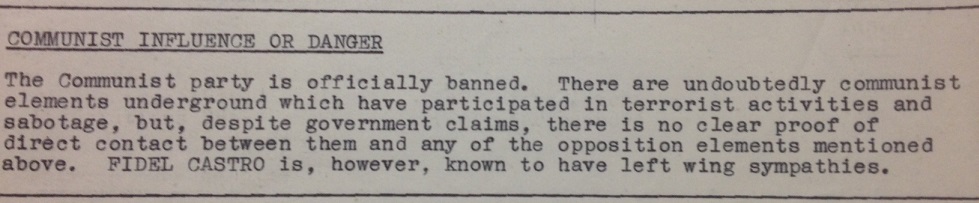

The rumours, however, proved to be well founded. Just four months later, in November 1956, Castro stormed back to Cuba aboard a yacht full of fellow dissidents to start what became the revolutionary war. The following year, as interest in him picked up pace, Castro broke onto the annual ‘Leading personalities’ list compiled by the British Embassy in Havana. In that first official British profile, from the 1957 list, he is ‘Suspected of Communist sympathies’ but no more than that. The short portrait goes on to depict him as having ‘a considerable number of sympathisers throughout the island’ and states that he has ‘come to be regarded as a romantic hero of the Robin Hood type’ (FO 371/126466).

Profile of Fidel Castro in the 1957 report on Leading Personalities in Cuba (catalogue reference: FO 371/126466)

Castro and his fellow revolutionaries, who called themselves the 26th of July Movement and included his brother Raúl and Che Guevara, stayed hidden in the forested peaks of the Sierra Maestra for most of the next two years, waging guerrilla warfare. As they did so, the British Embassy and their colleagues at the Foreign Office haphazardly constructed an impression of the man and his aims. Whether or not Castro was a communist was of primary concern and became the cause of increasing speculation as his rise to prominence gathered momentum and his seizure of power drew closer. In June 1957 the Ambassador in Havana since 1956, Stanley Fordham, sent his appraisal of the political situation in Cuba to London:

‘The main threat to his [Batista’s] regime comes from Dr. Fidel Castro[…]. What is the programme of this relatively young man? So far as one can gather, it is first to overthrow Batista, then to abolish all the existing political parties as being corrupt and inefficient relics of the past, and finally to set up a government of enlightened, forward-looking patriots who would introduce sweeping social reforms, including a large measure of nationalisation of both Cuban and foreign companies. It is not a programme which fills me with any enthusiasm. I do not doubt that many of those who support Castro are patriotic idealists who genuinely wish to make Cuba a better place; but he himself is reliably reported to have taken an active part in the Communist-inspired riots in Bogotá in April 1948, and I cannot help feeling that any revolution engineered by him would result either in chaos or else in something closely resembling Communism.’ (FO 371/126467)

Despite these assertions from one of its ambassadors, the Foreign Office kept an open mind, still unsure what a Cuba under Castro would look like. Just a month later, in response to another report filed by the Embassy in Havana, Robert Pease at the Foreign Office points out that ‘So far, Castro’s policy has been simply anti-Batista; if he is joined by more “respectable” opportunists some idea of his eventual intentions may emerge’ (FO 371/126467).

Down from the mountains

On New Year’s Day 1959, Batista fled Cuba aboard an aeroplane, marking Castro’s victory. The British, like the Americans, were quick to declare official recognition of the new Cuban Government. The mood among diplomats was cautious but welcoming, reflecting the still blurred picture they had of the revolutionary leader. His ‘left wing sympathies’ had become fairly well documented but there was recognition that he had not declared himself, or the revolution he had masterminded, communist – perhaps because he did not consider himself so or perhaps, as some thought, because he thought it prudent not to.

The portrait of the man himself, aside from his political beliefs, was similarly hazy; whether he was personable or prickly, tunnel-visioned or open-minded and how it would be best to deal with such an individual were key details all still largely unknown.

From a secret report sent by the British Embassy in Havana, January 1958 (catalogue reference: FO 371/132164)

In his first report of the personalities in the new Cuban Government the British Ambassador attempted to look ahead in the following appraisal, dated January 10 1959:

‘Fidel Castro has been the inspirer and undisputed leader of the anti-Batista revolt ever since he landed with some eighty men in November, 1956. […]There are still some lingering doubts about his personal political ideology. It has been established that as a young man, he was involved in communist intrigues in Colombia, and although he is probably sincere in disclaiming any present communist affiliations, he still seems to entertain a number of theories – at least in the domestic sphere – which can only be described as left-wing. On the other hand, he appears to be a convinced Catholic and a thorough-going idealist in matters of social reform. He is a non-drinker and smokes, if at all, in moderation. […]

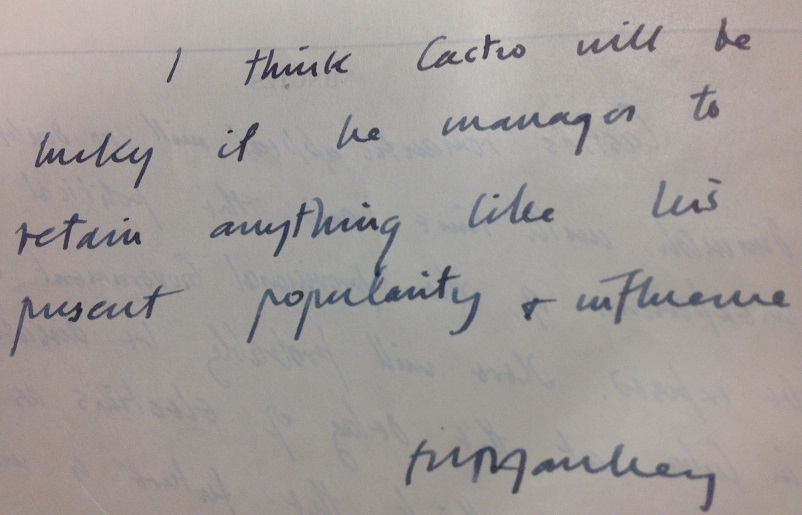

‘Of his personal energy, drive and magnetism there can be no doubt; but for this, he could never have kept his men going for over two years of guerrilla warfare. Equally, there can be no question of his present popularity. […] Romantically bearded, with his cohorts of battle-scarred veterans recalling the liberation fighters of sixty years ago, it is neither blasphemous not exaggerated to assert that for the great majority of Cubans, intoxicated by recent events, Castro represents a mixture of José Martí, Robin Hood, Garibaldi and Jesus Christ. Whether the revolutionary leader can survive as a constitutional statesman – whether, shorn alike of his beard and his Messianic appeal, he can continue to command the same influence – is another matter, regardless of whether he himself maintains his ideals unsullied.’ (FO 371/139398)

On receipt of this report, the Head of the American Department at the Foreign Office, Henry Hankey, predicted that ‘Castro will be lucky if he manages to retain anything like his present popularity and influence’ (FO 371/139398).

Henry Hankey of the Foreign Office evaluates Fidel Castro’s future in January 1959 (catalogue reference: FO 371/139398)

Related blog

British diplomats on Castro, 1959-1963: in the global spotlight

File FCO 7/5 is interesting as it reveals what the response was by Castro to Che Guevara’s death was, after their split. As far as the UK was concerned there was the issue that Cuba exported sugar, a valued commodity in the mid-1950s at a time when rationing had stopped in the UK in 1953.

The Leyland buses need by Castro to replace those destroyed by the Bay of Pigs invaders were probably of great significance that sugar. The 700,000 to one million tons of sugar that Cuba once exported to England, were readily replace in times of peace in Europe….

it is wise to view Ernesto Guevara as the ruthless, ambitious but incompetent guerrilla he was shown to be in Cuba, Africa, and in Bolivia.

Guevara was not the heroic figure his myth presents. He commonly separated from his command before contact with the enemy. His wounds were always minor and to a great extent contrived. For instance, the sling that held his arm in statues was caused by a fall from a roof …

[…] techadmin on December 22, 2016 British diplomats on Castro, 1953-1959: mystery man2016-12-22T09:11:04+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

My rough drafts include these notes”

“….Uncle Norman’s marriage to Aunt Manuela seemed, as the subtext of the letter clearly indicates, disqualify the information itself in his mind. My father mentioned that they (the British Embassy staff) subjected Norman to much ridicule behind my uncle’s back, laughing at his name change from Norman Henderson, to Jose Norman, ignoring his successful popular music career under that name,74 and implying that somehow this diminished the importance of his communication. Mr. Oliver also caught static from Graham Greene, in letters to the Times (presumably the London Times), Oliver writing in a restricted communication ..”

Provided with this kind of information, even the Head of the American Department of the British Foreign Office, Henry Hankey (mentioned above in relation to the 1940 Kakar disaster under estimated the Fidel Castro, writing: “Castro will be lucky if he manages to retain anything like his present popularity and influence’ (FO 371/139398).” It was not until Herbert Marchant, an old hand since the 1930s at dealing with communists in eastern Europe, became Ambassador to Havana that it became clear to the British Foreign office what was really happening. And the future Sir Herbert, was left with the task salvaging what he could and saving as many lives as he could.

Unfortunately, and especially for my father, Henry Hanky, had become an unwitting source for John Cairncross (one the infamous Cambridge communist spy ring) * And thus it has to be presumed that all that went on in the British Embassy in Havana was known to the Soviets, who in all probability, passed it along the Castro Government.

*Bacon, Kelsey 2012 The Cambridge Ring A Biographical Account of Five King’s Men Who Spied for Stalin JR/SR Honors Project Faculty Advisor: Professor Jeffrey Burds, March 22, 2012- Digital Repository Service https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/downloads/neu:376939?datastream_id…”