This month sees the launch of England’s Immigrants 1330-1550, a major new research database by the University of York, in partnership with the Humanities Research Institute (University of Sheffield) and The National Archives.

The vibrant nature of the population of the British Isles owes a great deal to the steady flow of immigrants over the past two millennia. Invasions by the Romans and Normans, sanctuary sought by the Protestant Huguenots, or the need for a workforce encouraging West Indians to immigrate all have had a part to play in making Britain the nation it is today.

Yet there are some gaps in our knowledge, particularly during periods where there were not large swathes of people moving into the country. This is particularly so for the late middle ages, following the expulsion of the Jews from England by Edward I in 1290, and before the arrival of the Huguenots in the 17th century. This was a period of dramatic social change, as Europe was ravaged by the Black Death in the mid fourteenth century and England was at war with France and her allies. At the same time, many industries were booming and trade was buoyant.

Against this backdrop, people were choosing to move around Europe, seeking opportunities or escaping hardship. The British Isles themselves were not a united nation, and the English administration regarded its neighbours – particularly Scotland and Ireland – as aliens, the term by which foreigners were identified in the middle ages.

The England’s Immigrants 1330-1550 database is now shedding new light on this hidden age of population movement, revealing extraordinary evidence of England’s immigrant population in the later middle ages. This work is the result of a three year project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) directed by Professor Mark Ormrod, of the University of York’s Centre for Medieval Studies, who headed a team of researchers based in York at and here at The National Archives.

The database is accessible to all and is a fully searchable and interactive resource, from which data can be downloaded. The website also supports the researcher with guides to the various counties and documents, and provides case studies of interesting individuals, which demonstrate just how much we can learn from our immigrant ancestors.

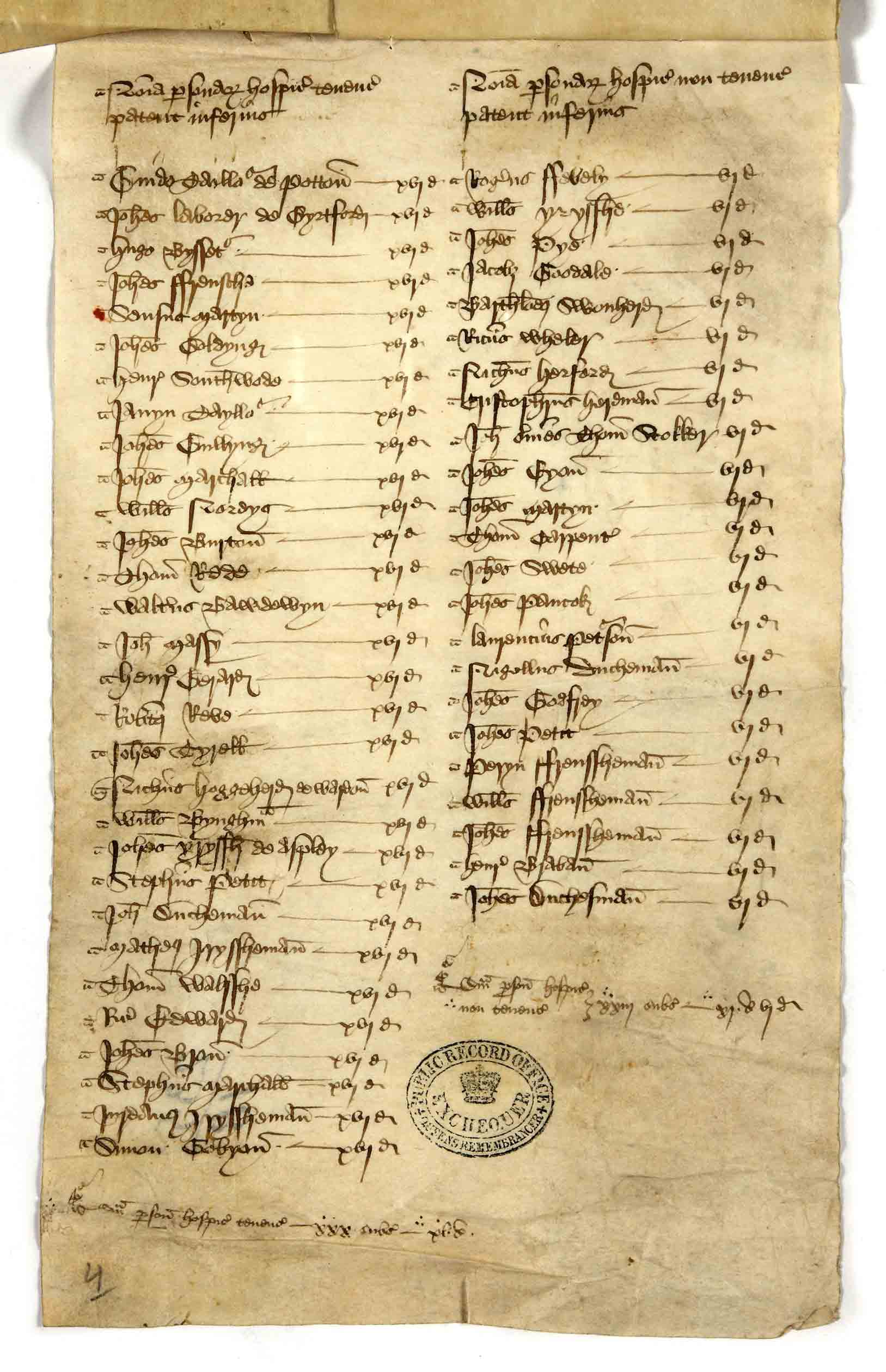

The vast majority of the documents used to create the database are held in our collections. The central information is drawn from taxation records. In the mid-fifteenth century, as a response to growing tension against England’s immigrants, a series of alien subsidies were granted by parliament. As a consequence, we are left with hundreds of records of names of aliens and where they lived in England, providing us with a snapshot of the make-up of England’s resident immigrants.

Other records from the period also survive, including various letters patent on the Patent Rolls, detailing requests for immigrants to remain in England and be treated like denizens. All of this information has been gathered onto the database providing easy access to complex data for the first time.

It reveals evidence about the names, origins, occupations and households of a significant number of foreigners who chose to live and work in England in the era of the Hundred Years War, the Black Death and the Wars of the Roses. As a result, the project contributes to debates about the longer-term history of immigration to Britain, helping to provide a deep historical and cultural context to contemporary debates over ethnicity, multiculturalism and national identity.

Alien poll tax inquests, commissions and particulars for Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire, 1442-3 (catalogue reference: E 179/235/18)

The database contains the names of a total of 65,000 immigrants resident in England between 1330 and 1550. In one year, 1440, the names of 14,500 individuals were recorded, at a time when the population of England was approximately 2 million.

Taking into account gaps in the records, the researchers estimated that one person in every 100 was from outside England. They were found in all counties, from Cornwall to Northumberland, in hamlets as well as in major ports. Their nationalities ranged from people from other parts of the British Isles, including Scots, Irish and Channel Islanders, to mainland Europeans from Portugal to Sweden, and from Greece to Iceland.

In many cases the occupation of the individual is known, from highly skilled craftsmen such as goldsmiths and weavers – many of whom were Flemish – to agricultural labourers. Three Flemish weavers from Diest in Belgium lived and worked in St Ives, Huntingdonshire, in the 1330s; and John Lammyns, a goldsmith from Antwerp, lived in Bristol in the 1430s and 1440s.

The database also reveals that aristocratic households brought back foreign servants from English-occupied France at the end of the Hundred Years War. Sir John Montgomery of Faulkbourne, Essex, had five foreigners working in his household in the 1440s. Many ordinary families of traders, artisans and workers chose to migrate to England. Walter, a minstrel from Germany, settled in London in the late fifteenth century with his entire family, including his mother, wife, three sons and three daughters.

One of the surprises revealed by the research is the number of resident immigrants who lived and worked in rural areas, rather than in towns and cities. The research reveals how such people integrated – and sometimes clashed – with English people, suggesting much about how our ancestors used language, dress and behaviour as symbols of national identity.

Members of the research team will be giving a talk on England’s Immigrants 1330-1550 at The National Archives on Thursday 9 April as part of the public talks programme. They will demonstrate the database, show how it relates to the original documents, and be able to answer questions about the project.

[…] find out more take a look at TNA’s blog post in which Dr Jessica Lutkin and Dr Laura Tompkins explore the database and medieval immigration in […]

[…] today’s blog post Dr Jessica Lutkin and Dr Laura Tompkins explore the database and medieval immigration in more […]

[…] read the full blog by Doctors Lutkin and Tompkins go to http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/englands-immigrants-1330-1550/, or view database […]

When you say the records are searchable, have you really got a program which reads medieval writing?

Hi Rothes,

Unfortunately not! The researchers on the project, including Dr Lutkin, have translated and transcribed the information from the original records and put it into the database, making them electronically searchable.

I hope that this explains the process!

Dr Laura Tompkins

Sadley I have tried to look at this database today (19 March) from several links all without success.

Hi John,

Sorry that you have been unable to access the database. We have tested the links in the blog and they all appear to be working fine.

Could you please try again using this link:

http://www.englandsimmigrants.com/

If you still cannot access it could you let us know what internet browser you are using and what, if any, error message you are receiving. We can then look into what the problem might be.

Dr Laura Tompkins

Those interested in the English Immigrants database may also be interested in the Wealden Iron Research Group’s on-line database (www.wirgdata.org) which includes those associated with the iron industry in the English Immigrants site as well as many other later ‘alien’ ironworkers whose presence has been recorded by the late Brian Awty.

“… to Europeans from Portugal to Sweden, and from Greece to Iceland.” Given the sensitivity demonstrated here to a current issue–immigration–I find it regrettable that no such sensitivity is evident towards another current issue: Europe. It is too commonly the practice to refer to `Europe’ as if we were not Europeans and as if the British Isles was not part of the European continent. All this is redolent with political overtones and practice can seem like endorsement. Would it not be more appropriate to refer to `fellow Europeans’ or to `continentals’?

That said, the database is going to be very useful, especially for those of us interested in migration to England’s second city, Norwich, before the well-known`headline’ migration from the 1560s onwards.

Hi Victor,

Thank you for your comment. No political statement was intended when describing medieval immigrants from Portugal, Sweden and Greece as ‘European’, but we have changed this in the text to ‘mainland European’ to make this clear.

We’re glad you find the resource useful.

Dr Laura Tompkins

I hope this project will be extended beyond 1600 to encompass the Walloon and Huguenot immigrants. including my Hersin ancestors who arrived some time unkown between 1625 and 1660.

My ancestors were Mitchell. They settled in the district of Halifax. I assume they were the Michel’s from the Brabant low country are in the Netherlands today. There is a record of Flemish weavers coming to Yorkshire in 1336. They were invited in by King Edward III. I am trying to understand which port they would have arrived in England. Can you help me with this? I assume they left Flanders by boat with their dismantled loom and spindle from Dordecht. Much appreciated if you can shed light on any of this.

Hi Jocelyn,

Thanks for your comment.

Unfortunately we can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

Best regards,

Liz.