On 5 August 1914, the Aliens Restriction Act was quickly passed by parliament the day after war was declared on Germany requiring foreign nationals (aliens) to register with the police, and where necessary they could be interned or deported. This act was chiefly aimed at German nationals and later other enemy aliens living in the United Kingdom, but the legislation and subsequent orders-in-council affected all foreign nationals in this country.

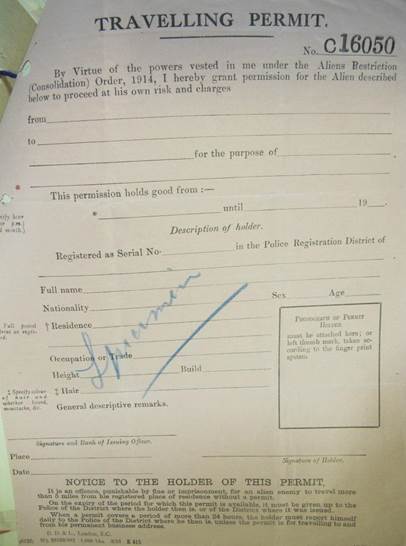

Specimen travel permit (catalogue reference: HO 45/11522/287235)

The first Aliens Restriction Order was also issued on 5 August 1914 (1914/1161) and this was quickly followed by two other orders-in-council on 10 and 12 August (1914/1170 and 1229) and a fourth on 20 August (1914/1258). These were brought together as the Aliens Restriction (Consolidation) Order 1914/1374 on 9 September. They:

- designated ports of arrival and departure for neutral aliens

- designated prohibited areas forbidden for enemy aliens

- imposed restrictions on items and goods that could be brought into or taken out of the country

- imposed travel restrictions on enemy aliens and their movements

Men of military age who were categorised as enemy aliens were arrested and interned, although for the most part this was done peacefully and men reported to temporary holding camps while more permanent internment camps were set up. Few records of individual enemy aliens have survived; the records of the Prisoner of War Information Bureau were destroyed by bombing in 1940. Two of the official lists of German subjects military and civilians interned in 1915-16 survive in The National Archives, in WO 900/45 and WO 900/46.

The War Office was responsible for housing and looking after enemy alien civilians, who were treated in the same way as military prisoners of war. The Home Office was responsible for the registration of aliens, through the police forces, and for taking of enemy aliens into custody. This resulted in inter-departmental conflict between the two in the early days of the war. Criticism was unfairly directed by MPs in parliament, the press and public opinion at the Home Office and Home Secretary. It is remarkable that all four wartime Home Secretaries – three Liberals (McKenna, Simon and Samuel) and one Conservative (Cave) – were firm but fair, not pandering to the jingoistic and xenophobic anti-German feeling that was generated during the war.

After the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915, there was a serious threat to public order; anti-German riots occurred in many cities. The Prime Minster H. H. Asquith announced tougher restrictions in parliament on 12 May, which came into effect on 13 May. As a result 19,000 enemy nationals were interned, although some 24,000 men and 16,000 women remained at liberty. Those of enemy origin who had naturalised were not interned. An Aliens Advisory Committee for England and Wales was set up with two sub-committees; one dealt with internment matters, and one with repatriations. There was also a separate committee for Scotland. Their proceedings were held in private and not published and unfortunately their records have not survived.

German civilian prisoners of war – Knockaloe Camp, Isle of Man, 1915 (catalogue reference: HO 45/11522/287235)

The number of internees rose during 1915: by July there were 26,173 and the number reached a peak in November 1915 of 32,440. Over 15,000 men applied for exemption, of which only 7343 were successful. Claims for exemption could be made on national or personal grounds. National grounds included occupational skills or experience that was of value to the country and the war effort. Personal grounds could include age and infirmity, length of residence in the UK, marriage to a British-born woman and a son or sons serving in the British armed forces. Length of residence was usually 35 years or more to gain exemption and a son or sons serving with the forces did not guarantee exemption. Some 6,000 men with sons serving were still interned during the war.

As the law was at this time, British-born women who had married foreign nationals (who had not naturalised) acquired their husband’s nationality. Many British born women therefore found themselves to be enemy aliens during the war. Except in a very few cases women were not interned.

Lloyd George’s coalition government of December 1916 saw a review of all cases of exemption that had previously been granted, but resulted in few further internments. In 1917 some internees were being released on parole to undertake work of national importance, mainly agricultural, but resistance to employing enemy aliens and the limitation of the type of work available meant that most had to remain in the camps.

In 1918 there was a further wave of anti-German feeling in the spring and summer with initial German successes on the Western Front and war weariness. Cases were again reviewed, further restrictions were placed on aliens and a reconstituted advisory committee met from July. By the end of October 1918 it had reviewed some 3,000 cases, but only 300 were interned and 220 recommended for repatriation. The majority of previous decisions were upheld.

With the coming of peace restrictions on aliens were not removed but continued and extended by the Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919:

- there were penalties for incitement to sedition, or promoting industrial unrest

- there were restrictions on employing aliens in the merchant service

- aliens were barred from working in the civil service

- aliens could not change their name without official permission (except women on marriage)

- former enemy aliens were to be deported, unless granted a licence to remain

- those who during the war were exempted from internment, or repatriation, did not face deportation

- registration with the local police remained in force

Post-war restrictions on aliens remained and the pre-1914 freedom of movement without passports was never to be restored. Few aliens registration records survive locally in county record offices. The National Archives was a sample of Metropolitan Police Aliens Registration Office: Sample Record Cards in MEPO 35.

Recommended background reading:

- J C Bird, Control of Enemy Alien Civilians in Great Britain, 1914-1918 (London: Routledge, 2015, 1st Edn 1986)

- Panikos Panayi, Prisoners of Britain: German civilian and combatant internees during the First World War (Manchester University Press, 2012)

Thank you for this article.

I have one question however. My great grandfather was the grandson of a German immigrant to London’s East End, sharing the same surname which I too now hold. Although he was a pacifist at the time, he still felt it necessary to anglicize ‘Wissner’ to ‘Winser’ so to maintain employment. But with the Aliens Restriction Order 1914 restricting name changes, would people like him have been bound by this despite in such cases being non-German speaking grandchildren of German immigrants?

I recently restored the family name back to Wissner, hence my interest in how far this legislation went, as to what exactly defined an ‘alien enemy’.

It states here that very few women were ever interned. Under what circumstances might a German woman have been interned? (I ask because a female German ancestor was not only interned in Britain but subsequently died of the mistreatment she experienced at the hands of her English captors. It led her English husband to commit suicide. Why is this history not more widely acknowledged??)

Is it correct to say that individuals born in the United Kingdom were not at risk of internment? My grandfather left the U.K. in 1915 under fear of internment but he was born in scotland (to German parents). I would imagine it was a hostile environment for a person with a German surname though.

My paternal Grandfather Frederick Martin, was a young German immigrant from a small village in Baden Wurtenburg. He settled here peacefully and worked in East London until the outbreak of WW1. As a young German national, he was classified as a “category A” enemy alien and interred for the duration of the war. Leaving his English wife and 3 young children to fend for themselves with no state benefits of any kind. My Grandmother (nee Reinhardt) had 3rd generation German ancestry and both her father and brother were volunteer British soldiers. Her brother died at Passchendaele in 1917. My Grandfather was not released until his deportation in 1919! He was a fit young man when he was first interred but was a physical wreck when he returned to Germany and died shortly after. My Grandmother returned to London with her 3 children, including my father. Both he and his brother served as Royal Engineers in WW2.

My Maternal grandfather was a German baker living in MANCHESTER with his wife and 8 children. In 1914 he was interned and after the war was reported back to Germany as he had not had English citizenship. My grandmother died in 1917 leaving her 8 children without mother of father. My mother was the youngest child age 7 yrs old

None of the siblings ever spoke about it They were afraid of admitting their German descent. It remained secret for over 2 generations

Were women who were born in Russia considered as enemy aliens? My grandmother was born in Russia and I can’t find any record of her being naturalised so I assume she retained her Russian nationality.

My Great Grandmother emigrated to London on 1901 and married an Austrian in 1912.

In 1916 he forged papers as a Swiss Citizen and was caught and sentenced to 5 years in Portland Prison. He is not on the 1921 Census in Portland Prison so I assume he was deported. My Great Grandmother is also not on the 1921 Census so im assuming she may have been deported with him as she was American.

Does anyone know where the deportation records could be found or the release records from prison.

My paternal grandfather Albert Bruno Harry Maennling was born in 1883 in Berlin, Germany and emigrated to England in about 1900. He married in 1905. He was the head waiter at London’s Basil Street Hotel. He was rounded up with other German Nationals after the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 and interred somewhere in England for the duration of WW1. By all accounts he was treated very well. Whilst interred he manufactured an intricately carved hand mirror in dark wood with an oval bevelled mirror which I have. I would like to know of others who have a similar experience.

I would love to find out more about my German great great and great Grandmothers. I’ve been told they were interned but I’m not sure how to find out more. Their surname was Hameman I think and my great grandmother Margaret, married my great grandfather Frank Gordon in Yorkshire.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

I am resarching rural communities on Salisbury Plain during the Great War. In November 1917 one Australian soldier murdered another Australian in Sutton Veny Camp. A quick coroners court initially decided that it was suicide, until the intervential of Inspector W T Scott Wiltshire Constabulary who informed the Chief Constable of his suspcions then informed the Director of Public Prosecutions.(DPP). Scott used ballistic tersting a the dead carcasses of sheep to successfully show that it was murder and was commended by the DPP On his record of service Scott was also commended by MI 5 twice, one commendation was for work connected with aliens. Does anyone know what this may have been about. As far as I know there was no internee camp located either on Salisbury Plain, or, indeed Wiltshire. If anyone can assist I would be extremely grateful.