Although tucked away in cool storage for future generations to enjoy, the archival crown jewel that is Domesday Book (in fact composed of two volumes, Great and Little Domesday) was once a working record regularly seen and consulted. We are therefore delighted to send it to a temporary summer home, to be displayed outside London for the first time in living memory, in a major exhibition at Lincoln Castle.

Great Domesday will be accompanied by an illustrious court of seven other medieval documents including Nichola de la Haye’s seal – highlighting the historic role of the city’s female constable – and a letter by Henry VIII describing Lincoln as one of the most ‘brute and beastly shire of the kingdom’.

The Great Domesday, volume 2 (catalogue ref. E 31/2/2)

931 years of history

When William the Conqueror gave his ‘deep speech’ of Christmas 1085, outlining his plan to survey England in its entirety, few could have foreseen that the resulting Doomsday Book would still fascinate people 931 years later. Used for centuries as proof of who-owned-what-and-where, it also gives an invaluable insight into the structure of society.

In addition to enormous intangible and historical value, Domesday is a precious object and work of art that elicits awe and curiosity. As such it has undergone many investigations, regstorations and preservation campaigns over its long history.

Conservation then

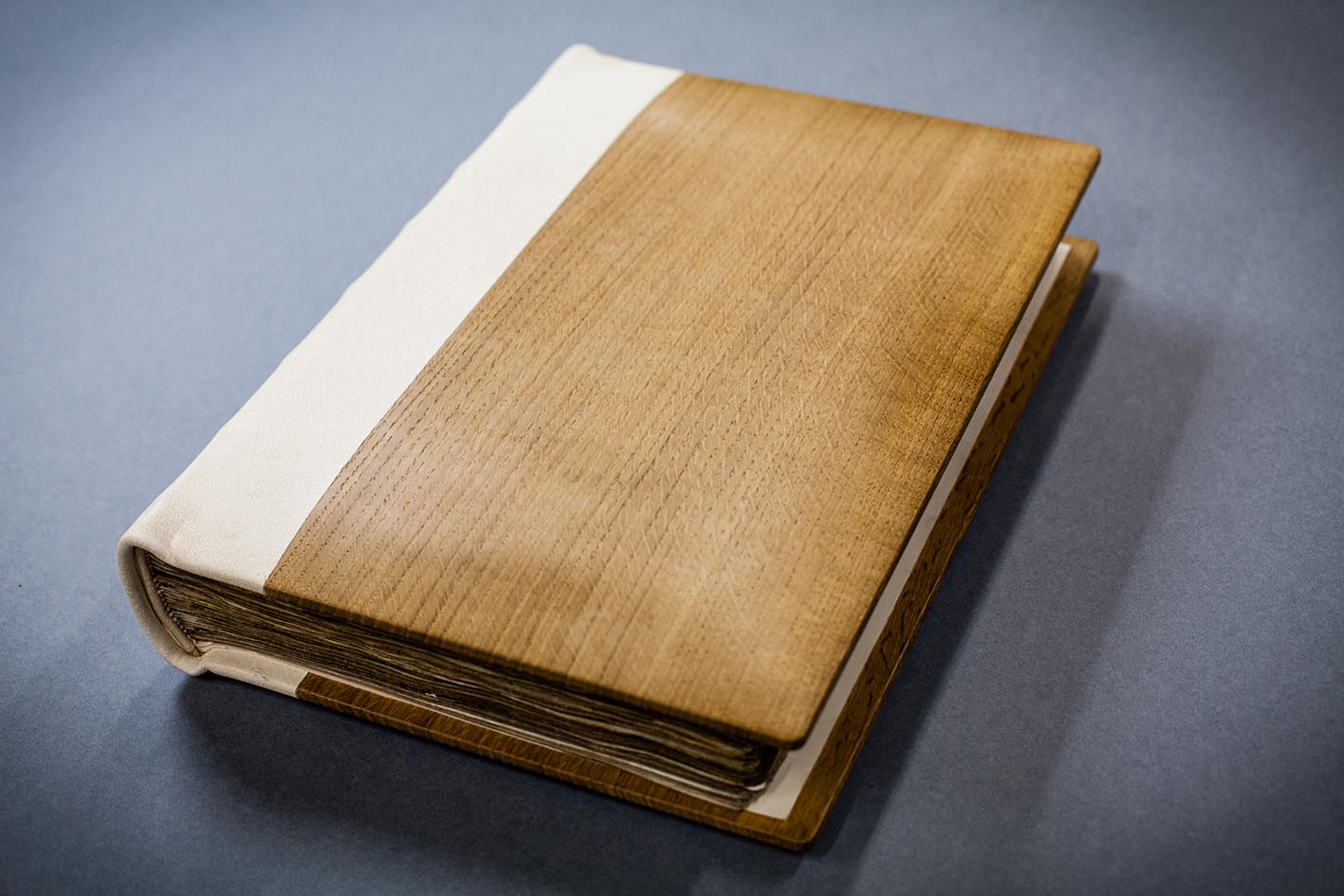

We do know that Great and Little Domesday each underwent six binding campaigns; materials and techniques have changed over the ages. In 1869 it was, for instance, slipped into a ‘Sunday best’ befitting its status – ornate stamped leather with silver bossed corners. By 1952 post-war sobriety was in order with a chaste, ‘realistic’ binding that reflected Domesday’s original working nature.

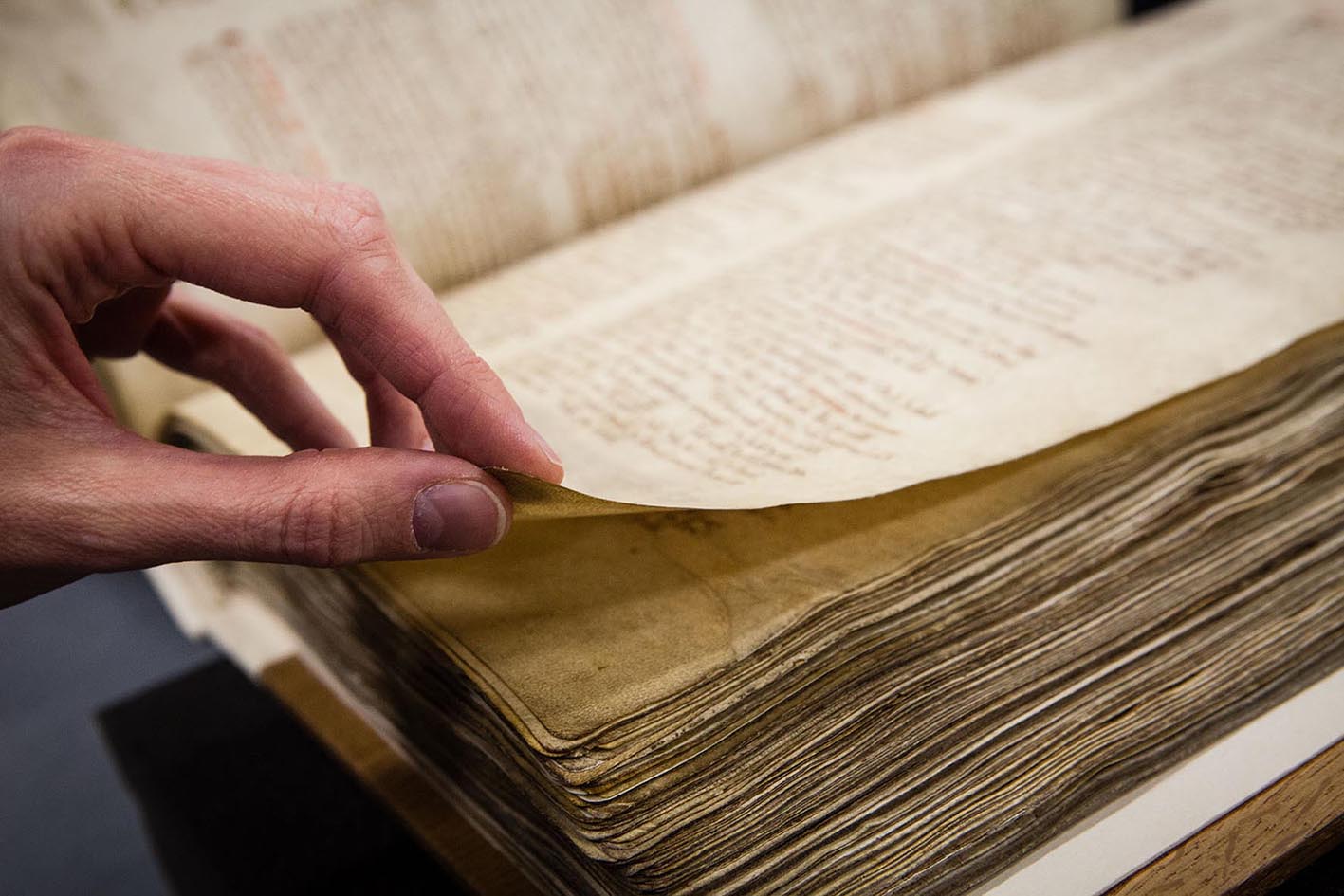

The most recent rebinding campaigns started in 1984 in anticipation of the book’s 900th anniversary. Our Collection Care department began an extensive two-year programme to better understand Domesday and to address problems caused by the 1952 binding, which was too tight and had caused creasing by being applied wet onto dry parchment.

Each parchment leave was thoroughly repaired – in places to address problems caused by earlier conservation work – humidified and pressed to remove the creases. To reduce stress on the books’ structures and to make them easier to handle, conservators decided to rebind the original two volumes into five.

Great Domesday Book, rebound in 1986 (catalogue ref. E 31/2/2)

An insight into the making of Domesday

The 1980s project told us much of what we know about Domesday. An expert calligrapher established that most of Great Domesday was written by one person, suggesting an extremely fast-paced production – the pressure to work with speed and accuracy is something many can relate to…

He seems to have used a consistent method at first, folding four parchment sheets in half to form 16-page quires or folios, ruling each page using the pricking (piercing) of the fore-edges as guides and planning to fit one county to each quire. However, he had to add or remove sheets and half-sheets as he progressed, realising not all counties would fit into the same number of sheets. He changed from marking 44 lines per page to 50 and then 53, before finally giving up and using no lines at all. He left gaps and made additions to completed pages to incorporate new information as he went along.

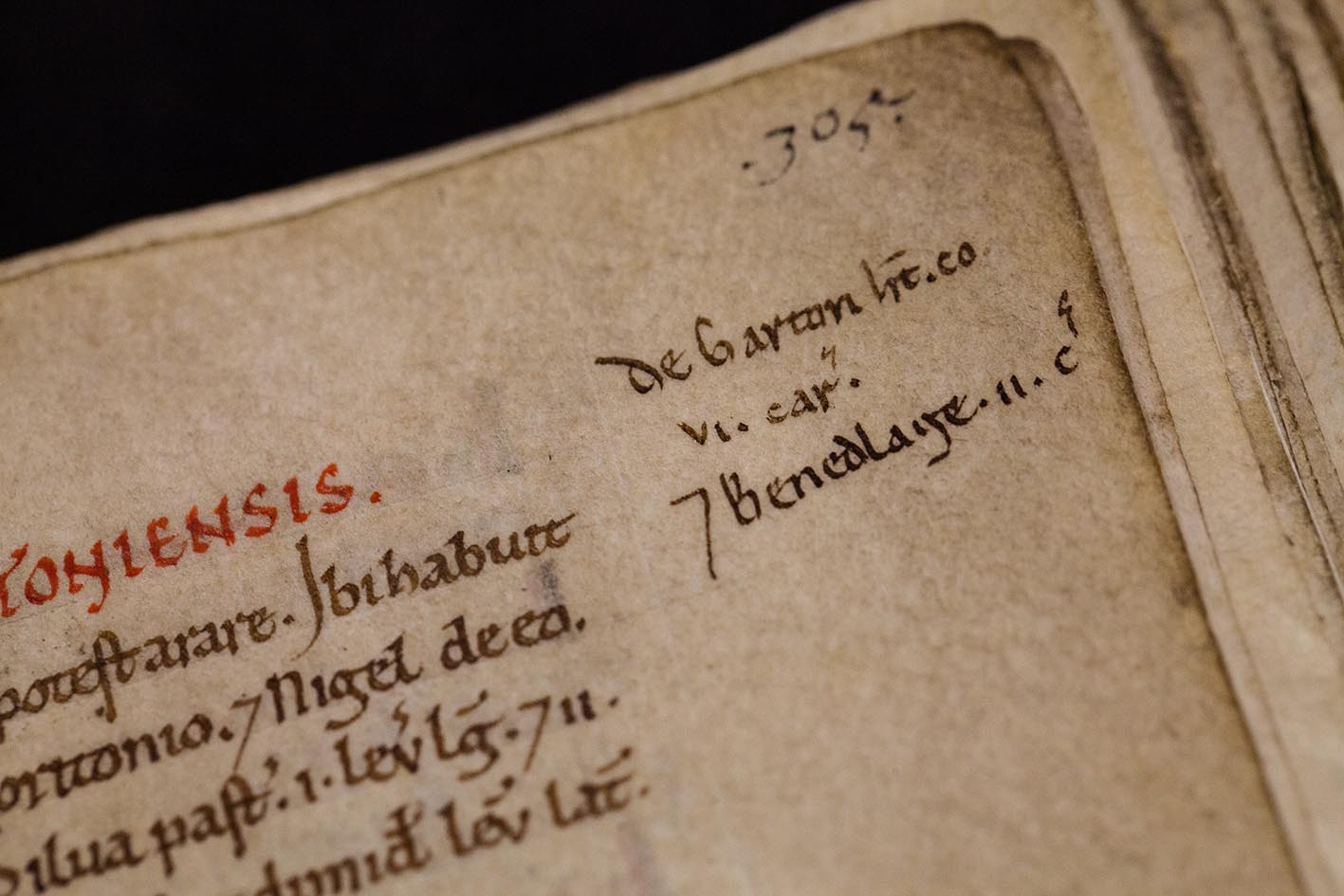

Further research established that variations in the colour of the iron gall ink were probably caused by large batches being prepared to save time, and that the red ink ranges from vermilion (in Great Domesday) to red lead (in Little Domesday). Carbon dating confirmed that the parchment dates from the 11th century – proving its authenticity, to everyone’s relief – and gave more information on the dating of former cover boards, called ‘Tudor boards’, which we still hold.

Great Domesday, volume 2, detail of the inks (catalogue ref. E 31/2/2)

Conservation now

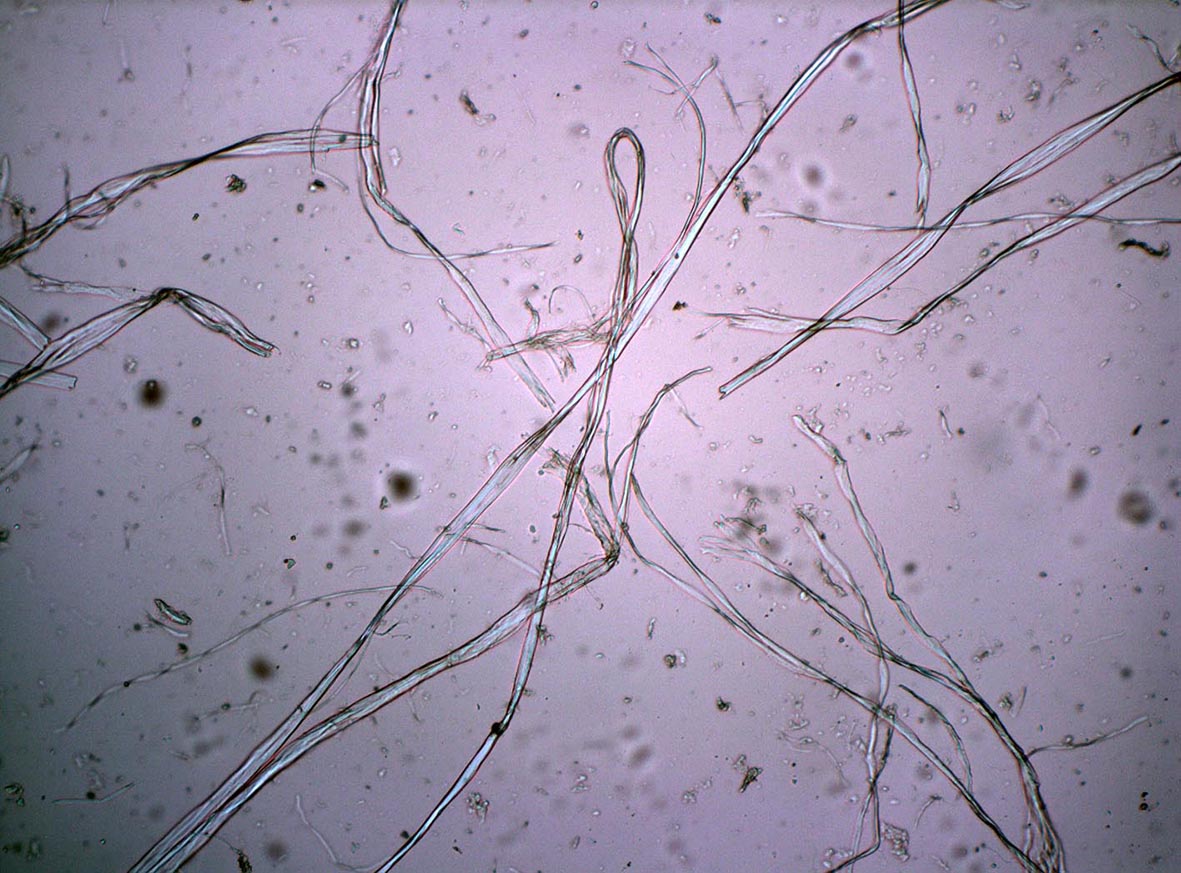

In 2006 a new collaborative project was launched to research the structural integrity of the parchment. Technological advances allowed researchers to go beyond the thorough visual examinations of past decades and scrutinize the book on a nanoscopic level.

Tests were carried out to study the oxidation of the collagen (which leads to weakened physical stability) and to assess its fibrillar structure, as well as to determine the shrinkage temperature of the parchment fibres to study their sensitivity to the environment. These tests were carried out on 0.1mg samples using respetively high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), X-ray diffraction and the micro hot table method – the heating of fibres in water to observe their shrinkage activity. Scientific probing also revealed that calfskin had been used in the parchment in addition to sheepskin.

Parchment fibres during shrinkage test on the micro hot table

The results showed that although appearing visually sound, many parchment fibres were degrading on the microscopic and chemical level, leading in many places to gelatinisation (the formation of a stiff layer of surface gelatine which hinders natural contraction and expansion and can provoke ink and pigment degradation).

This phenomenon has been identified on 66% of the leaves and is a result of the fluctuating environmental conditions endured during the book’s long life (including wartime storage in a damp prison!) as well as wet conservation treatments which we now know can contribute to the breaking down and fragmenting of the fibres.

Making medieval history cool for future generations

All these findings have informed a different approach to the conservation of our medieval documents, favouring preservation rather than intervention and anticipating symptoms rather than focusing on their cure. It has in this regard been decided that, except in case of force majeure, Domesday would undergo no more interventional treatment and will be kept in cooler, drier conditions to slow degradation.

We hope that our oldest public record will continue to age gracefully, for as long as possible, at a stable 14 degrees Celsius and 35% relative humidity. Don’t miss the opportunity to see it in the flesh this summer, before it has to return to its cool royal quarters!

The Domesday Book is on display at Lincoln Castle 27 May – 3 September in parallel with the Battles and Dynasties exhibition at The Collection.

[…] are far more treasures to see in the exhibition. Part of Domesday Book is on display, the first time it has been shown outside London since it became part of the Public Record Office […]

very expensive but good

Glad you enjoyed the post, there is so much to say about Domesday! If you’re in London, make sure you go see it at the British Library (and there are some associated talks and events I believe, in case your thirst for Domesday-knowledge has not yet been quenched).