An international arms dealer known by the universal nickname of Zedzed. Corrupt payments seeking to provoke a war between two European powers. The widespread buying up of newspapers and the use of these to spread propaganda. Demands of backhanders in the form of money and honours in return for illegally influencing the policies of independent countries.

This sounds more like the plot of a James Bond film than the activities of an elected government, but as a series of Foreign Office files held here at The National Archives show, this was exactly the policy pursued by the British government during the First World War.

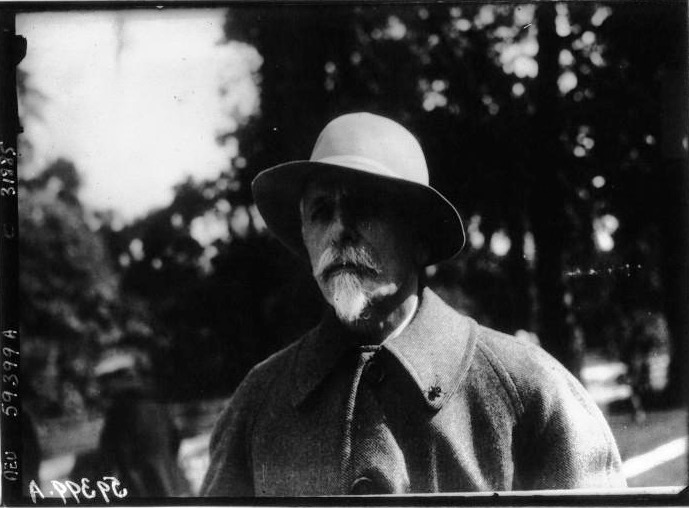

The Merchant of Death: Sir Basil Zaharoff (WikiCommons)

The man at the centre of the entire scheme was Sir Basil Zaharoff, Zedzed, who was also widely referred to as the merchant of death, Europe’s man of mystery or the wickedest man in the world. Zaharoff appeared to be living proof of the old adage that fact is stranger than fiction. The son of a Constantinople commodity dealer he reportedly started out on his business career running brothels and starting fires as part of a protection racket run by the Constantinople fire brigade. He moved to Britain posing as Prince Zacharia Gortzacoff, a Russian army officer. He married Emily Boroughs in October 1872 but in the following year he pleaded guilty at the Old Bailey of stealing from a fellow merchant and promptly fled (HO 27/165).

He turned up in Cyprus and America, where he made money in the railroad business, bigamously married a New York heiress and eloped with her to Rotterdam. Finally he secured himself a position as an agent for the Swedish armaments manufacturer Thomas Nordenfelt, where his undoubted talents began to show. Famed for his unscrupulous methods and a willingness to ferment political trouble in order to boast arms sales, Zarahoff quickly established himself as the leading arms dealer in Europe. By 1897 he was working for the British armaments giant Vickers and was as likely to be selling battleships as he was rifles. This success brought fabulous wealth and led to Zaharoff moving in the rarefied circles of European high society. Intrigue and shady practices were, however, in Zaharoff’s blood and the outbreak of the First World War gave him the opportunity to exploit these at a whole new level.

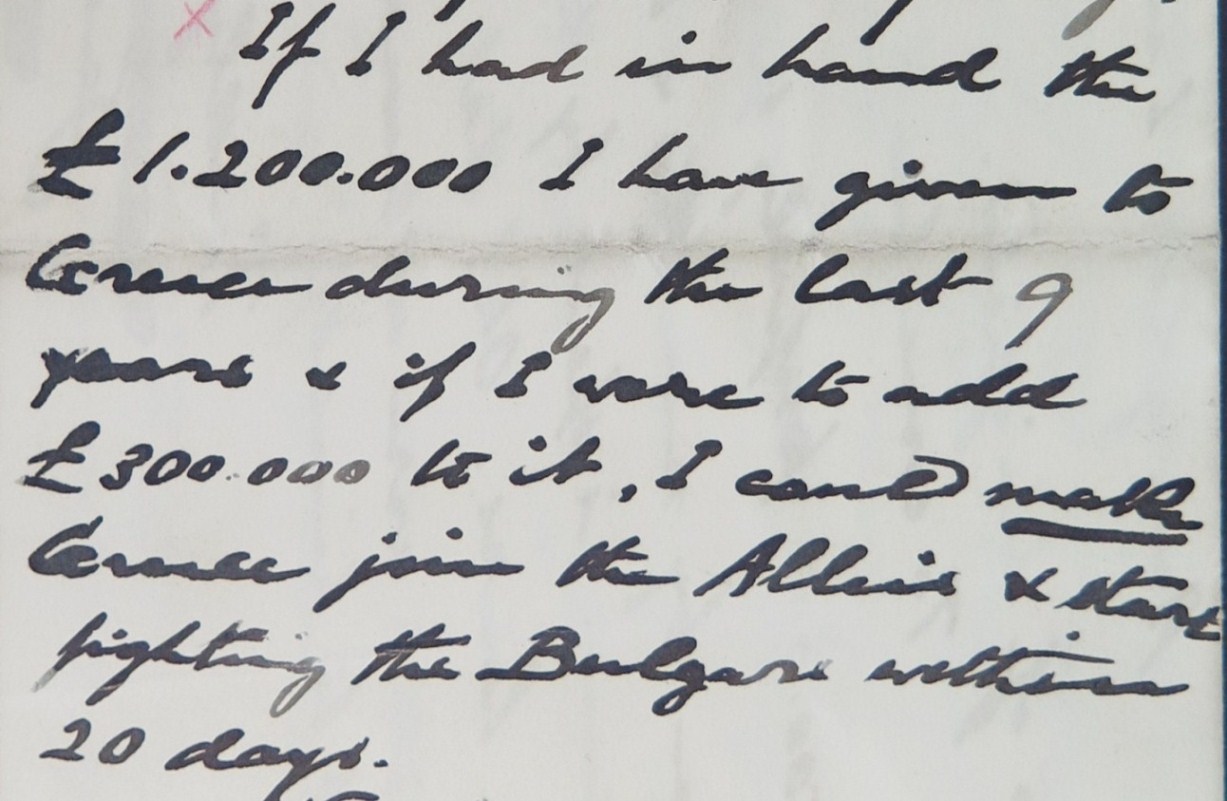

It started with letter Zaharoff wrote to his friend and director of Vickers, Sir Vincent Caillard, in November 1915. In it he claimed that ‘if I had in hand the £1,200,000, I have given to Greece during the last 9 years and if I were to add £300,000 to it, I could make Greece join the Allies and start fighting the Bulgars within 20 days.’ He continued that ‘all that is needed is to buy the Germanophile papers, also 45 Deputies and on Frontier Commander’. (FO 1093/47) It is clear that Zaharoff intended to bribe elements in the Greek army into provoking an incident on the Bulgarian frontier and then use the rest of the money to ‘persuade’ the Greek government into declaring war.

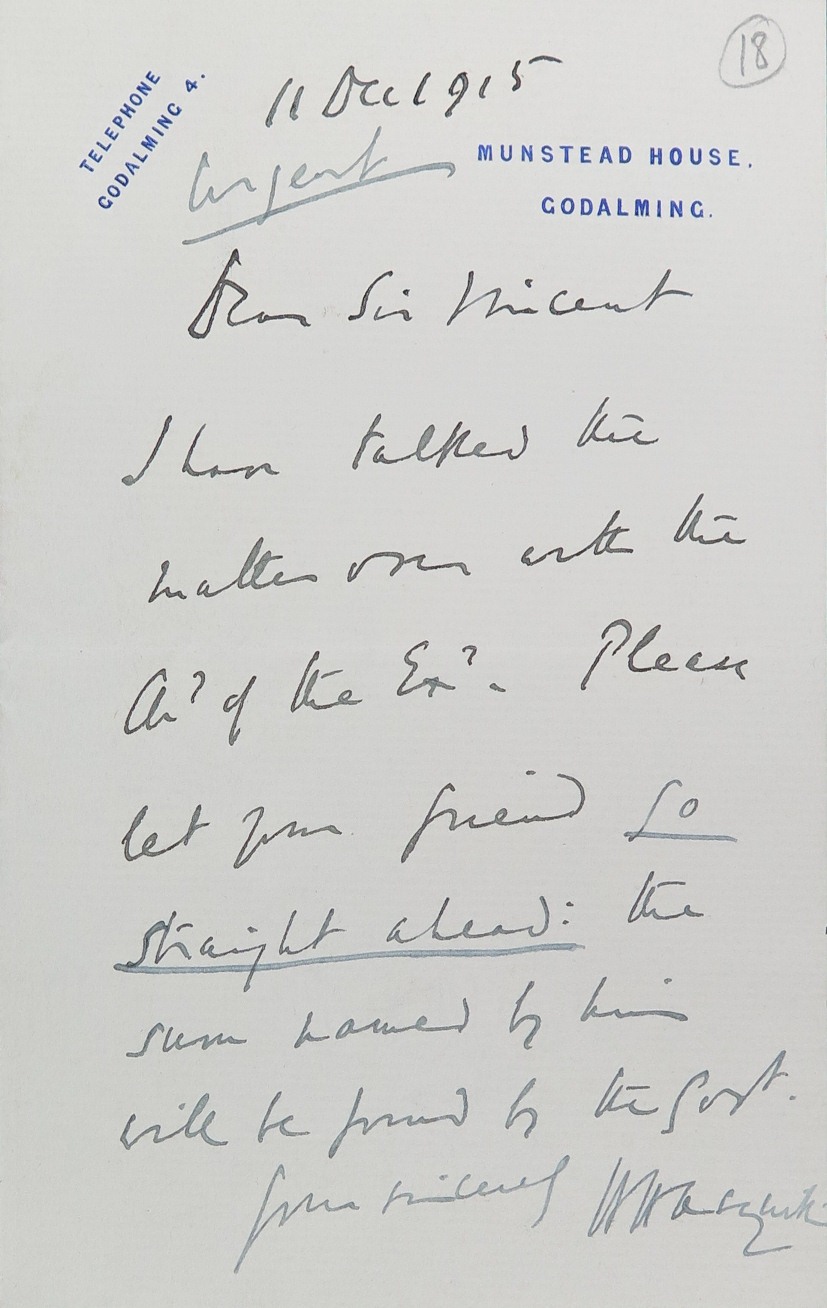

Caillard showed this letter to the influential Lord D’Abernon who, far from being horrified by Zaharoff’s suggestions, brought the matter to the attention of the British government. A few days later Caillard wrote back to Zaharoff saying that key figures including the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, were generally keen on the idea. They expressed concerns about Zaharoff’s plan to provoke a crisis on the Greco-Bulgarian frontier, although this was not based on any moral principle. Instead, ‘they are unwilling to face the risk… this might be traced back to the source’. Regarding the underhand funding of pro-British factions within Greek politics the British government had no such qualms and Asquith wrote to Caillard to say that ‘I have talked this matter over with the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Please let your friend go straight ahead: the sum named by him will be found by the Government’. (FO 1093/47)

The correspondence between these hugely influential men has an air of farce to modern eyes, particularly the refusal to use people’s actual names. As such the Prime Minister became ‘the Chairman’, the Chancellor of the Exchequer was ‘the Treasurer’ and together they were simply Caillard’s ‘friends’. Zaharoff, naturally, was Zedzed, or sometimes simply Z.

Zaharoff, mainly operating from the safety of the Hotel de Paris in Monte Carlo, began to distribute monies in support of key figures, especially the liberal politician Elefthérios Venizélos. At the same time he pursued a campaign of propaganda both in Greece and beyond through the Radio Telegraph Agency which he had set up. By March 1916 he could report to Caillard that ‘our preparation of fermenting Greco-Bulgarian frontier troubles has begun to give fruit.’ (FO 1093/48). Asquith clearly agreed, writing to Zaharoff ‘I beg on behalf of His Majesty’s Government to tender to you their sincere gratitude for the most valuable service which, at a critical time you have rendered the cause of the Allies.’ Later in 1916 Zaharoff would declare that ‘the last Greek Parliament, not once proposed or voted anything against the Allies. I am rather proud of that work.’ (FO 1093/48)

Despite failing to get Greece to enter the war on the British side, Zaharoff soon set his sights on an even bigger prize, bribing the Ottoman Empire into leaving the war. The Ottomans had joined the Germans soon after the outbreak of war, and Allied attempts to force their surrender through military operations at the Dardanelles and Gallipoli had failed miserably. Zaharoff proposed a very different option. Through a contact, Abdul Karim Bey, Zaharoff was approached by the Ottoman military commander Enver Bey. Enver wanted to discuss coming to an arrangement with the Allies. At secret talks Abdul Karim told Zaharoff:

‘all talk of a separate peace with Turkey, was out of the question, because the Germans held Constantinople in their iron grip, but added why not open the Dardanelles to you treacherously? What is it worth to the Allies in American dollars payable in America?’ (FO 1093/48)

Caillard discussed the matter with the Prime Minister who felt that ‘it is rather an off chance but worth risking a certain amount for’. Asquith was particularly concerned about the risk of the Turks taking the money before the ‘goods’ were delivered. As if to clarify Caillard wrote to Zaharoff to say that ‘by “goods delivered he means the delivery over to us of the forts and the opening of the sea-way’ [Dardanelles]. (FO 1093/50) By the time the British decided the proposal was ‘worth “risking the toss”’ the Turks had begun to have second thoughts and the opportunity slipped.

Zaharoff was not a man to be easily dissuaded and he felt it was worth having another go. In May 1917 he decided to go to Switzerland ‘where “by accident”, I am bound to run across some of our Ottoman friends and that might be a way of re-opening the subject.’ The initial overtures proved successful and Caillard discussed the matter with the new Prime Minister, David Lloyd-George. He was very keen on the whole idea, but listed an extraordinary set of demands which led Caillard to note that ‘it was a pretty tall order to negotiate separate terms of Peace on the basis of the practical dismemberment of the country with which you would be negotiating.’ Zaharoff met his contacts in Geneva where he was told that ‘Turkey was ruined and lost and that Enver & Co were willing to throw up the sponge on “reasonable conditions” and get out with their lives’. The “reasonable conditions” included safe passage to New York and $12,000,000 paid into an account at J P Morgan’s. Unsurprisingly Lloyd-George was not entirely convinced but was ‘full of courage about the business, and quite ready to take reasonable risks’. (FO 1093/52)

A number of meetings took place between Zaharoff and Abdul Karim in various Swiss hotels throughout 1917 and 1918, but they always came unstuck on the Turkish demand that a $2,000,000 retainer be paid prior to the start of any serious negotiations. The British were unwilling to take this gamble. Although the discussions intensified in autumn 1918 it is not clear that they had any direct impact on the Turkish decision to sue for peace in October 1918.

It is difficult to work out the direct impact of Zaharoff’s underhand dealings. The British government invested considerable effort and money with little obvious result, but both Asquith and Lloyd-George seemed happy with the proceedings. The willingness of the British to act upon Zaharoff’s suggestions shows how much war changed the moral perspective of these democratically Liberal politicians. As if to cap it all Zaharoff felt that he deserved to be recognised for all the effort he put into these shady dealings. He lobbied hard to be awarded a Grand Cross of the British Empire – quite a step for a former brothel tout from Constantinople. As with most things in life Zaharoff got his way. In his own words this was his reward, his ‘chocolate’. (FO 1093/52)

[…] An international arms dealer known by the universal nickname of Zedzed. Corrupt payments seeking to provoke a war between two European powers. The widespread buying up of newspapers and the… Go to Source […]

Fascinating! I have had an interest in Zaharoff for a long time. I read about him sporadically and by chance today I came across your article above together with a referencto a release of Foreign Office and Cabinet Office papers, mostly concerning the Cambridge Spy Ring but also referring to the personal files of Sir Basil Zaharoff. See:

http:www.ibtimes.co.uk/cambridge-spy-ring-what-sensational-new-mi5-files-tell-us-about-soviet-trators-guy-burgess-1525242.

Author:L Andrew Lownie 23/10/15. You probably know about this but just in case …I thought that you might be interested. The personal files should be worth a look at.

Is there any chance you could let me have your sources for the above piece, please. I feel like doing some more reading!

Thanks and best wishes

Peter

Peter Naden

I dont know why such documents are not digitized which would make it easier for historians who can’t travel to London. Please digitize many documents from various series covering the period 1914-1923.