Our Collection Care department is giving a new lease of life to a set of 19th and 20th century moulds of seals. This collection of over 6,500 moulds includes depictions of heraldry, weapons and armour, buildings, fashion, landscape, plants and animals. The moulds are taken from seals held at The National Archives: the original seals date from 1085 to 1953. Their imagery will soon be accessible for the first time through The National Archives’ catalogue, Discovery.

PRO 23/6157 Great seal of England and Wales

I spoke to preventive conservation assistant Amy Sampson and two members of her volunteer team, Janet Morrow and James Pestell, to find out about this work in progress and what they most enjoy about it.

Amy Sampson

Digitising things is not typically what I do. My everyday work is about preventing damage to the collection: monitoring for pests, making sure the environment in our repositories stays cool and dry, and providing document handling training. I was aware of our collection of 6,500 seal moulds, made from plaster and silicone rubber, but it hadn’t been used for some time – and there seemed to be so little information available about what it contained that I was concerned about its future.

I support the volunteers in scanning, data input and in researching the moulds, working closely with an historian and expert in digital preservation. Between us, we make sure all the information recorded about the moulds is accurate, and that the images are ready to be uploaded to Discovery.

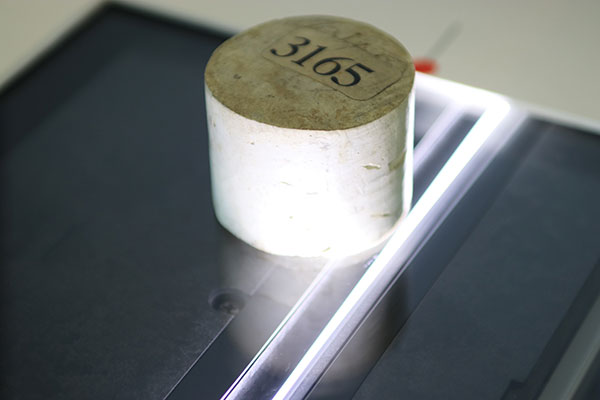

Scanning a seal mould. Photo by Jacqueline Moon.

There are lots of things I find really exciting about this project: I’ve learnt more about seals, sealing practices and imagery than I expected to. I can now identify seal types – ecclesiastical seals, for example are vesical-shaped rather than round. I’ve also become more familiar with the signs and symbols used on heraldic seals, including a Fess – two horizontal lines drawn above and below the center of the shield – and a Checky – several rows of squares of two alternating tinctures.

Janet Morrow

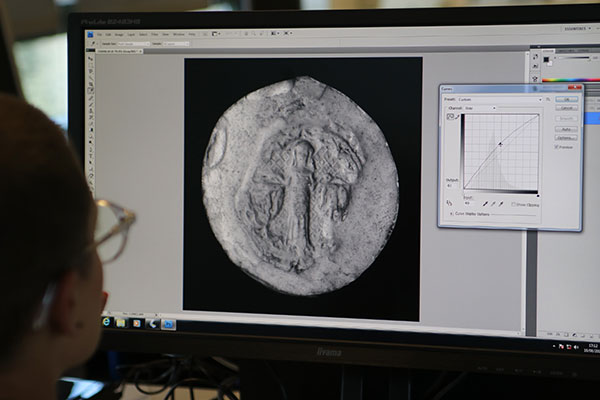

As a keen family historian who’s spent many hours poring over online transcriptions and indexes, I was aware that many of the record descriptions I was relying on were produced by volunteers. I felt the need to do my bit and put something back into the archive community and, as I was already visiting The National Archives for my own genealogy research, I decided to volunteer. I come in for a day a week to help scan the seal moulds on a flatbed scanner and manipulate the resulting images in Photoshop to make them clear and readable.

Checking the quality of the scan. Photo by Jacqueline Moon.

Sometimes the background information for the seal moulds needs checking and I love it when occasionally we get to handle – with training! – original parchment documents with seals attached, or when we do detective work in old printed catalogues to establish exactly what date the seal is from and who it belonged to. I’m particularly touched when we see an original seal which has the seal-maker’s fingerprint in the wax: it’s an extraordinary human connection to a person from the distant past.

I have a professional background in communications in the broadcasting industry – nothing at all to do with archives or history – although I do enjoy the visual arts, and for me the seals are like miniature works of art.

Checking the card index of the seal moulds. Photo by Jacqueline Moon.

James Pestell

I was introduced to the project last year. I had some spare time that I wanted to fill productively and this seemed like a good fit with my interests in culture and history. I’ve learned a lot about Photoshop, taxonomy, heraldic language, medieval monastic hierarchies… well, you just never know when that’s going to be useful in life! Knowing that the results of our work are available online worldwide for all to explore and study, whether you’re a casual browser or a serious scholar, is amazing. Digitising this extraordinary collection feels as if we’re reanimating the past.

The seal moulds are stored in drawers. Photo by Jacqueline Moon.

I’m one of a team of volunteers. I come in once a week and add information about the seal moulds to a spreadsheet: the date of the seal, the document it was attached to, its size and colour. This information will appear with the image of the mould in The National Archives’ catalogue. Sometimes this involves some fairly detailed research: I might need to check one of the volumes of ‘A Descriptive Calendar of Ancient Deeds’ held in The National Archives reading rooms to find a date or who the seal might have belonged to; at other times I need to check the original documents to find out what colour the seal was.

I’m a marketing and communications consultant with a background in broadcasting, higher education, the public sector and the performing arts. I have never been involved with a project like this before so it’s a great new experience for me.

It’s nice to know there are people who dedicated themselves to make sure important documents are protected and preserved in the correct way for us to access IL latter years to come.

My father in law was a Chaplin to the forces in Salonika- we have compiled a diary from his letters home – if it would be of interest would you like a copy?

We also have a letter from his nephew who wrote it at the time of the Christmas truce

– I understand there are very few letters written by anyone who was there available. We would like to keep the original but would be happy for you to have a copy. The young man who was a captain was killed a few weeks later so the letter means a great deal to our family.

Dear Mary,

Thank you so much for your kind offer.

Although we receive many generous offers of letters, photographs and other historical documents, unfortunately we can rarely incorporate them into our collection in a way that will allow others to access and make use of them. This is because the material we hold consists primarily of official records created by and selected from government departments and other public sector bodies.

The Imperial War Museum (IWM) collects certain types of material and is currently running a digital project – Lives of the First World War – that aims to bring together First World War material from museums, libraries, archives and family collections from across the world. IWM is holding local events for members of the public to scan and upload digital versions of their precious First World War memento items. You can find out more from their website.

Best regards,

Liz.