Economist Joseph Schumpeter popularised the term ‘creative destruction’ to describe the theory that technological advances make obsolete not just individual practices but whole philosophies, industries and ways of life.

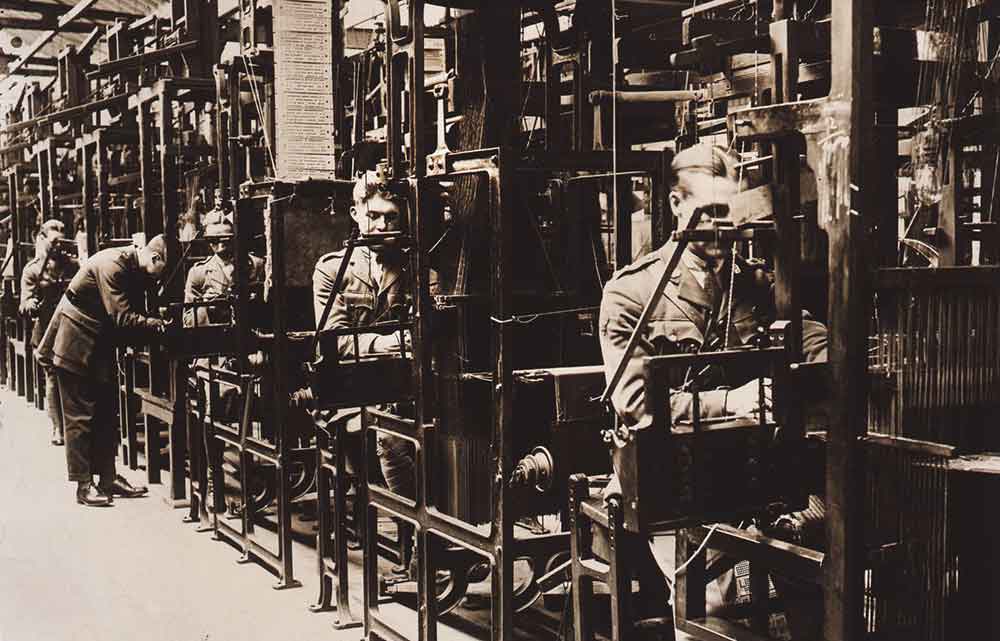

Civil Demobilisation and Resettlement Hand-Loom Weaving, 1918-19

We can find evidence for this idea in the historical record: for example, we can trace the ancestry of computing back through the development of punched-card textile looms in the 18th and 19th centuries. During the industrial revolution, weavers found their industry and way of life being disrupted by technological advances.

Reflecting on the challenge of digital records, what does creative destruction mean for our archival practice? What do archivists need to do to make sure we are not rendered obsolete by rampant technological change?

One option might be leave the challenge of digital archiving to another profession, or rely on another, newer kind of memory institution to figure out how to manage digital archiving. However, at The National Archives we believe that archivists are best placed to curate and sustain digital archives, so long as we embrace the disruption. (You can read more about our plans – and our intention to be disruptive – in our digital strategy.)

There is a strong argument that digital archives grown from within established archives, like ours, are best equipped to develop the new capabilities we need to preserve digital records.

Here are three of the reasons why.

1. We are already trusted

There are good reasons to trust established archives with digital preservation. We have a proven institutional commitment to successfully preserving unique, precious and fragile things, while making them accessible to the public. We also have a strong tradition of ensuring the provenance and the authenticity of our collections.

There are good reasons to trust established archives with digital preservation. We have a proven institutional commitment to successfully preserving unique, precious and fragile things, while making them accessible to the public. We also have a strong tradition of ensuring the provenance and the authenticity of our collections.

Our track record gives us ‘trust capital’, which would otherwise be hard to gain and that the digital archive can draw down from. The culture, practices and hard-won reputation of the established archive confer legitimacy on the digital archives we create and sustain. This is a crucial part of justifying the rights and privileges we need so that we can do the extraordinary things we have to in order to preserve digital records over generations of technological change.

2. Prospect of longevity

Archives aren’t ephemeral, fly-by-night operations – we are long-established institutions, looking after collections that society and the state have viewed as important and have already kept for hundreds of years.

Our oldest records date back almost a thousand years. The National Archives exists as a result of the original Public Record Office Act, passed in 1838 to ‘keep safely the public records’. The relevant legislation and archival practices have evolved over time, but we are still the guardians of the public record 179 years on. Applying Bayesian reasoning, this track record means that the likelihood for the ongoing existence of the archive’s collection, and the institution which preserve it, is comparatively very high – much higher than for any alternative. There is a very good prospect that the physical collection and the institution underpinning it will survive into the future – and the digital archive can draw down from this prospect of longevity.

3. Capacity to change

Over the years we have grown and changed, as have our beliefs about what ‘accessibility’ should look like. Advances in conservation science have altered our practices and our standards as we determine the best ways to preserve our collection. The people, location and governing law might all change but our core purpose and our dogged determination to preserve the public record are part of our institutional DNA and endure across the generations.

We’re committed to preserving the public record – in fact, we’re pretty passionate about it. But if we’re to keep doing this throughout the 21st century, we know we need to be able to adapt in response to government departments’ changing digital preservation needs.

The good news is that this is nothing new for us: we’re accustomed to change. We’re familiar with the evolution of records (for example, from letters to telegrams to telexes to faxes to emails). We take the inevitable and unceasing changes in government structures and legislation and day-to-day working practices in our stride.

Facing up to continual change

This all works in our favour, provided we accept that we can’t adapt just once: we have to commit to continual change.

Any digital preservation system we build is strictly temporary. Technology moves so fast that any system we construct will necessarily become obsolete, sooner or later. When that happens, we will have to be able to extract the records held within it, undamaged and unadulterated. Collections of digital records have to be able to survive successive generations of expendable systems that preserve them.

The disruptive archive has to be able to adapt and evolve incessantly, exploring the digital landscape in which it operates and understanding how that landscape is changing. It needs to continually make smart decisions based on razor-sharp situational awareness.

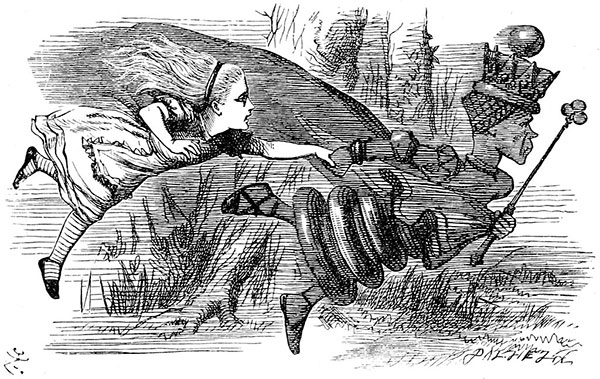

Or, in the words of Lewis Carroll’s Red Queen: ‘Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!’

Or, in the words of Lewis Carroll’s Red Queen: ‘Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!’

We’re going to keep on running, and being disruptive. We’ll carry on making tough decisions about how we turn our most stringently limited resource – which is, of course, money – into maximum benefit in a digital world that just won’t stand still for us.

It’s an interesting time to be an archivist

It is far early to reach a judgement on digital records given how recent it is but it is far easier to locate and see a paper record than a digital record and I would suggest that paper records will survive longer than paper records. We heard similar stories back in the early 1970s about the cassette recorders (does anyone remember them?). I understand that TNA are employing 150 people on digital records next year, which will impact paper records being processed. Incidentally the Public Records Act of 1838 centralised records that had been kept safely (in most cases) elsewhere in a variety of places.

[…] John Sheridan – The National Archives blog […]

As someone interested in the history of technology I’ve read a lot of case studies on disruption. I’m also an archivist. So, a comment.

In every case study I’ve read the incumbents have said ‘It won’t affect us because ‘. Just like this list. The underlying problem is that it’s hard for incumbents to see, let alone question, the assumptions on which they have built their business.

A particular problem occurs when organisations make assumptions about what their customers value. In this case trust and longevity. The organisations are almost always right. But what they miss is that their customers also value other things, and the best mix of ‘value’ for customers changes over time. It turns out customers value cost more, for example, or the ability to do new things.

To get back to tin tacks, I think archives have two disruptions at the moment, with another coming down the path.

The first is non archival storage. Why transfer records to an archive when non-archival storage is (relatively) cheap, and the actual transfer process is expensive?

The second is non archival access through ‘resellers’ of archival content. Unhampered by archival theory or budgets, they can provide more user friendly access and integration with non-archival sources.

The disruption that is coming down the track is machine organisation of archival material. This has the potential to radically change appraisal and sentencing, and also description and access.

A comment from my particular position as an digital archivist in a country where e-government is really pervasive.

I think there is a bit of truth in both the original post of John and the reply from Andrew – there is indeed a certain element of knowledge in archives which usual government departments (and their IT development bodies) lack. More specifically, I’ve seen far too many cases of digital implementations where the whole focus is on delivering a digital service and workflow, and no attention to longevity whatsoever. And at this point it’s the archivists who step in, ask the nasty questions and (based on their unique knowledge around embracing change) recommend the solutions which will allow the digital services survive not only for the next five years but indeed, into the future.

Yet, for me it’s also clear that we need to get rid of some of the current paradigms like “archives know best what the future user needs” and “archives as a repository”. We need, indeed to question whether current appraisal, description and access solutions are what the user needs, and rather start thinking about “packaging” our unique knowledge into implementable chunks which could be applied in any digital environment which needs it, in a way which allows to build any storage or access solution on top of that.

So, I certainly agree that archivists have what it takes to be a crucial part of the fast digital change but one of the core disruptions I see is that, in order to be effective, we need to think much more out of the box.. or rather “out of the repository”.