Sometimes myths grow up around a subject and become so well known that they obscure the essential story. I certainly found this to be the case with the story of the discovery of the anti-bacterial properties of penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming, who died 60 years ago on 11 March 1955. In fact, the processes by which penicillin was discovered and developed to an effective drug present a complex story. Similarly, there have been many reports in the media about the declining effectiveness of antibiotics and fears that some infectious disease will again become intractable. But the ‘antibiotic age’ is relatively short and ideas about resistance have been around since its beginning.

Alexander Fleming was born in 1881 into a farming family in Ayrshire, Scotland. He attended a local grammar school and, after a spell in a London shipping office, decided to follow his brother into a career as a physician. In 1903, he enrolled as student at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in Paddington, London, an institution with which his career became closely associated. He gained his degree with distinction in 1906, but he was really interested in research. He became an assistant to the distinguished bacteriologist Sir Almwroth Wright and completed a Bachelor of Science degree with gold medal in bacteriology in 1908.

Fleming had a distinguished career as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps during the First World War. He saw many cases of gangrene, septicaemia and tetanus, which were common and feared outcomes of wounds suffered in filthy conditions. The conventional treatment of wounds was the application of antiseptics but Fleming thought that this harmed the body’s natural defences, without killing the pathogenic bacteria concealed deep within. The best way to treat wounds was to encourage the supply of white blood cells that attacked bacteria.

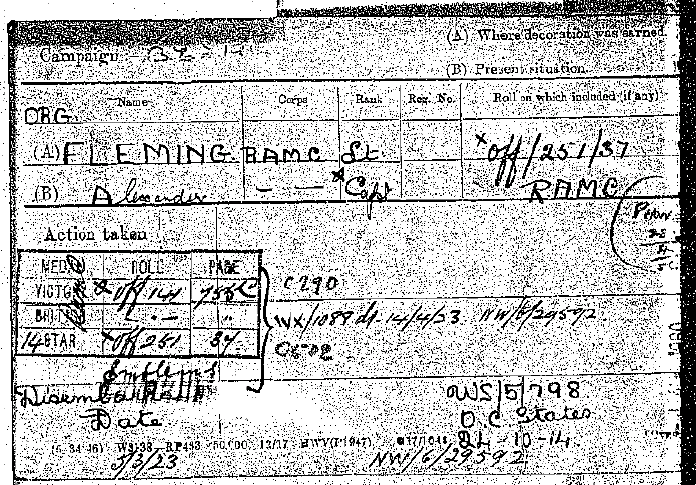

First World War medal card of Alexander Fleming WO 372/7/86054

Like many others, the experience of war had a profound on Fleming. When he returned to St Mary’s he took up research into the treatment of bacterial infections, drawing on some contemporary experimental results. He was interested in ‘lysis’, the destruction or dying out of colonies of bacteria. Bacteriologists studies bacteria by growing them as ‘cultures’ in flat petri dishes and introducing different substances to observe the effect. In 1921, Fleming found that a substance in nasal mucus seemed to destroy a type of bacteria when one of his dishes was accidentally contaminated. He called the substance a ‘lysozome’, but it was nearly seven years before another accident led to the antibiotic effects of penicillin.

Fleming had been cultivating staphylococci, a type of bacteria commonly found on the skin and responsible for a range of serious infections, including pneumonia, when he went on holiday on in August 1928. When he returned, he found that one of his petri dishes had been contaminated with mould. Strikingly, the bacterial growths in this dish had been destroyed. The effective mould was a type of Penicillium, so Fleming called the antibiotic agent in the ‘mould juice’ penicillin. Penicillin was found to destroy many other (but not all) types of bacteria. He also found that the ‘mould broth’ was non-toxic to animals and didn’t interfere with the leucocytes – a finding of key importance for the development of a practical treatment.

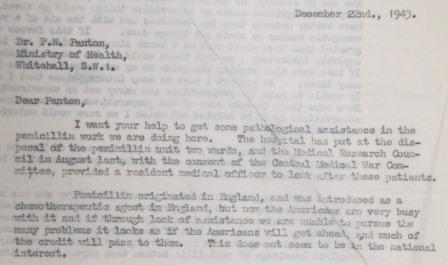

Letter from Alexander Fleming, urging the British government to fund penicllin research, 23 December 1943 FD 1/6889

Nevertheless, the problems seemed insuperable. Penicillin was very unstable and was present in tiny concentrations. Fleming himself saw penicillin as something that could be applied directly to the wound as an alternative to antiseptics, rather taken into the blood stream, and there was more general scepticism about the likely value of such ‘chemotherapeutics’.

He published his results in 1929 in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology, but the paper had little immediate impact. Fleming tried to encourage chemists to work on the practical aspects of producing penicillin in larger quantities, but perhaps his rather diffident personality hindered him in pushing the discovery. True, some sporadic work was carried out on penicillin in Britain and America during the 1930s, but would be over ten years before scientists made further important breakthroughs.

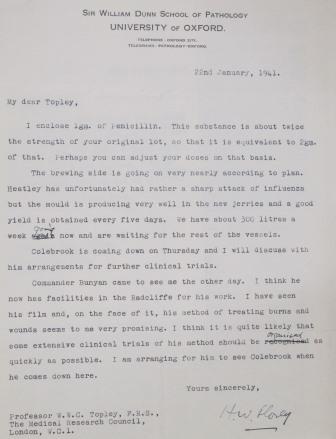

Supply of experimental penicillin, Howard Florey to Professor W C C Topley, 22nd January 1941 FD 1/6890

In 1940, a team of scientists at Oxford’s Dunn School of Pathology under the Australian Howard Florey and the German émigré Ernst Chain put in an application to study ‘bacterial antagonism’ to the Rockefeller Institute in the United States. Florey and Chain had read Fleming’s paper and included a study of penicillin in their programme. To cut a long story very short, the team soon demonstrated that the drug could be used to treat a wide range of bacterial infections and found means of isolating and purifying penicillin, thus making it safe for human use. Another member of the team, Norman Heatley pioneered methods for producing penicillin on a larger scale, which were passed to American and British pharmaceutical companies.

By the D-Day landings in June 1944 penicillin was revolutionising the treatment of wounded military personnel, and soon after the war it became available for civilian use. Some diseases, such as pneumonia, previously fraught with mortal danger became treatable and ceases to be a major cause of death, at least in the west. Soon, scientists discovered other antibiotics which were effective against a wider range of disease and the ‘antibiotic age’ was issued in.

Fleming was delighted on hearing of developments at Oxford and contacted Florey, who hadn’t realised that he was still alive. During the 1940s, he experimented with the use of penicillin at St Mary’s and in 1942 was instrumental in persuading the British government to take up the large-scale production of the drug. He feared that American scientists and pharmaceutical companies would gain the advantage in penicillin research.

Fleming received due recognition for his discovery. He was knighted in 1944 and awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1945, together with Florey and Chain, although Heatley was not included. In his Nobel lecture in December 1945, Fleming warned that bacteria could easily be made resistant to penicillin through under dosing and that inappropriate use might well lead to problems in future. As he put it:

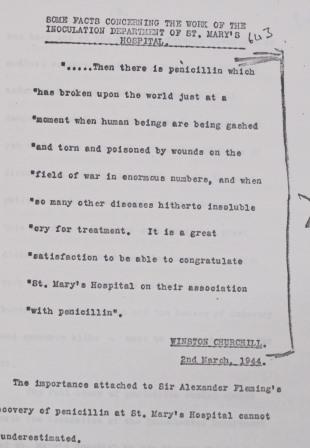

Text of a broadcast by the Prime Minister, Winston Churchil, 2nd March 1944 PREM 4/88/7

The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug make them resistant

A Fleming, Nobel Lecture, 11 December 1945 http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1945/fleming-lecture.pdf

Fleming continued to enjoy a distinguished career, becoming Emeritus Professor of Bacteriology at the University of London in 1948 and serving as Rector of Edinburgh University from 1951 to 1954. The worldwide tributes to Fleming which were received at the Foreign Office after his death on 11 March 1955 testify to his worldwide fame.

KBrown, Penicillin Man: Alexander Fleming and the Antibiotic Revolution (The History Press, Stroud, 2005)

R Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the the Present, (Harper Collins, London 1997)

D Wilson, Penicillin in Perspective, (Alfred A Knopf, New York, 1976)

[…] The National Archives: Death of Sir Alexander Fleming, discoverer of penicillin, 11 March 1955 […]

Nice article. I always love to hear the “real” story, not the fantastic one made up by hear-say. But there is an incomplete sentence that leaves one hanging. It is: He feared that American scientists and pharmaceutical…….. we can all guess what comes next, but there again, we would have hear-say and conjecture, though the conjecture is an educated guess. Should it read: that American scientists & pharmaceutical companies would patent the mold and the process of refining and producing penicillin and then charge out-rageous prices for it, thus limiting it’s availability to the world?

Thank you for this web site. I am excited to learn to use it.