On 24 August 1814, British troops under the command of Major-General Robert Ross captured the city of Washington and set fire to its public buildings, including the Capitol building and the White House. The events happened during the war of 1812, fought between British and American forces at sea and on land in America and Canada. America had declared war on Great Britain on 27 June 1812, citing four key reasons: trade restrictions and blockades imposed during the Napoleonic Wars, the impressment into the Royal Navy of British seamen serving on American ships, British defence of the Native American tribes against American expansion and territorial claims into part of modern day Canada that had not been sufficiently addressed following the American Wars of Independence and the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 (FO 93/8/2).

The plan

Following the abdication of the Emperor Napoleon in April 1814 and his exile to the island of Elba, British troops were no longer tied up in France. With naval superiority having recently been reinforced by the extension of the naval blockade to all ports of the United States of America (CO 37/72 folio 44), it was felt that a series of lightning strikes against major coastal cities along the eastern seaboard of the United States of America, would be likely to divert American forces away from Canada and to induce them to come to a peaceful settlement on terms that were favourable to the British government. At the direction of the British government, plans were drawn up by Rear-Admiral George Cockburn, Commander of the British fleet in North America, for targeted attacks on Washington and Baltimore, which, if successful, would be followed up by similar limited raids on New Orleans, Philadelphia and New York (WO 5/141 folios 40 to 43).

The orders

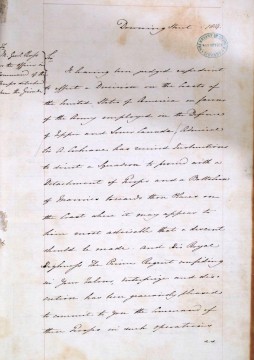

On 18 July 1814 Lord Bathurst, the British Foreign Secretary, sent the following orders to Major-General Robert Ross:

‘Sir, it having been judged expedient to effect a division on the Coasts of the United States of America in favour of the Army employed in the defence of Upper and Lower Canada, Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane has received instructions to direct a squadron to proceed with a detachment of troops and a detachment of marines towards those places on the coast where it may appear to him most advisable that a descent should be made. And His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, confiding in your valour, enterprise and direction has been graciously pleased to commit to you command of the troops in such operations as you may judge it expedient when on shore to undertake.

In addition to the force which may have been placed under your orders previous to your departure from the Gironde, you will on your arrival at Bermuda take under your command one other regiment of British infantry and one company of artillery which have been directed to proceed thither from the Mediterranean for that purpose. The amount of force which will thus be placed under your command [three regiments of infantry with a proportion of artillery, one regiment of infantry and one company of artillery and one battalion of Royal Marines with a proportion of Royal Artillery] will sufficiently point out to you that you are not to engage in any extended operation at a distance from the coast. …If, in any descent, you shall be enabled to take such a position as to threaten the inhabitants with the destruction of their property, you are hereby authorised to levy upon them contributions in return for your forbearance…’ (WO 6/2 folios 1-4).

The report

On 30 August 1814, Major-General Robert Ross, on board HMS Tonnant, in the Patuxent river, wrote to the Earl of Bathurst, the British Foreign Secretary, announcing the capture of Washington

‘My Lord, I have the honour to communicate to your Lordship that on the night of the 24 instant, after defeating the army of the United States on that day, the troops under my command entered and took possession of the city of Washington.

In compliance with your Lordship’s instructions to attract the attention of the Government of the United States and to cause a diversion in favour of the army in Canada, it was determined between Sir Alexander Cochrane and myself, to disembark the army at the village of Benedict, on the right bank of the Petuxent, with the intention of co-operating with Rear-Admiral Cockburn, in an attack upon a flotilla of the enemy’s gunboats, under the command of Commodore Barney.

On the 20th instant the army commenced its march, having landed the previous day without opposition: on the 21st it reached Nottingham, and on the 22nd moved to Upper Marlborough, a few miles distant from Pig Point, on the Petuxent, where Admiral Cockburn fell in with and defeated the flotilla, taking and destroying the whole. Having advanced to within sixteen miles of Washington, and ascertaining the force of the enemy to be such as might authorise an attempt at carrying his capital, I determined to make it, and accordingly put the troops in movement on the evening of the 23rd. A corps of about 1200 men appeared to oppose us, but retired after firing a few shots. On the 24th the troops resumed their march, and reached Bladensberg, a village situated on the left bank of the eastern branch of the Potowmack, about five miles from Washington.

On the opposite side of the river the enemy was discovered strongly posted on very commanding heights, formed in two lines, his advance occupying a fortified house, which with artillery, covered the bridge over the eastern branch, across which the British troops had to pass. A broad and straight road leading from the bridge to Washington, ran through the enemy’s position, which was carefully defended by artillery and riflemen.

The disposition of the attack being made, it was commenced with so much impetuosity by the light brigade, consisting of the 85th light infantry and light infantry companies of the army, under the command of General Thornton, that the fortified house was shortly carried, the enemy retiring to higher grounds.

In support of the light brigade I ordered up a brigade under the command of Colonel Brooke, who, with the 44th regiment, attacked the enemy’s left, the 4th regiment pressing his right with such effect as to cause him to abandon his guns. His first line giving way, was driven on the second, which yielding to the irresistible attack of the bayonet, and the well directed discharge of rockets, got into confusion and fled, leaving the British the masters of the field. The rapid flight of the enemy, and his knowledge of the country, precluded the possibility of many prisoners being taken, more particularly as the troops had, during that day, undergone considerable fatigue.

The enemy’s army, amounting to eight or nine thousand men, with three or four hundred cavalry, was under the command of General Winder, being formed from troops drawn from Baltimore and Pennsylvania. His artillery, ten pieces of which fell into our hands, was commanded by Commodore Barney, who was wounded and taken prisoner. The artillery I directed to be destroyed.

Having halted the army for a short time I determined to march upon Washington, and reached that city at eight o’clock that night. Judging it of consequence to complete the destruction of public buildings with the least possible delay, so that the army might retire without loss of time, the following buildings were set fire to and consumed – the Capitol, including the Senate-house and House of Representatives, the arsenal, the dockyard, the treasury, war office, President’s palace, rope-walk and the great bridge across the Potowmack: in the dockyard a frigate nearly ready to be launched and a sloop of war were consumed. The two bridges leading to Washington over the eastern branch had been destroyed by the enemy, who apprehended an attack from that quarter.

The object of the expedition having been accomplished, I determined before any greater force of the enemy could be assembled, to withdraw the troops, and accordingly commenced retiring on the night of the 25th. On the evening of the 29th we reached Benedict, and re-embarked the following day.’ (WO 5/141 folios 15 to 19)

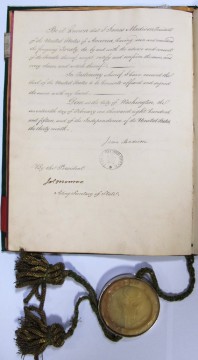

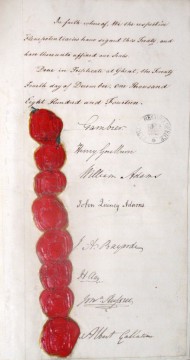

Ratification of Treaty of Ghent with the signatures of President James Madison and Secretary of State James Monroe. Catalogue reference: reference: FO 94/4

The Treaty of Ghent

As the campaign was being planned, negotiations were already underway between British and American Commissioners appointed to treat for peace. On 6 August four British delegates, Lord Gambier, Henry Goulburn, William Adams and Albert Gallatier met up with their opposite numbers John Quincy Adams, James A. Bayard, Henry Clay and Jonathan Russell in Ghent in modern day Belgium to negotiate a peace settlement. The first conference took place on 8 August 1814. On 27 September Lord Bathurst wrote to the British Commissioners announcing the capture of Washington and advising them of the steps they should take to press home the British claims as a result of the news (FO 5/101 folios 33r to 36v). However, this success was short lived. News soon filtered through that Major-General Ross had been killed during the subsequent Battle of Baltimore and on 8 January 1815 British forces were decisively beaten at the Battle of New Orleans. Although the Treaty of Ghent was signed on 24 December 1814, war raged on with successes on both sides until the treaty was finally ratified by the United States of America on 17 February 1815, bringing to an end a war that neither side had particularly wanted.

Re the Treaty of Ghent: my recollection is that Belgium as a country didn’t exist until 1830 and was still part of The Netherlands or am I wrong?

Yes, you are right David. I had meant to put in modern day Belgium. It is too much of a distraction in a short blog about Washington to describe the secession of the Southern Provinces of the Netherlands in 1830 to become the Kingdom of Belgium in 1831, but at least by this reply that is explained. Thank you for your comment. James

Sir. I believe that major general Ross was from Ireland. Indeed the small town of Rostrevor in county Down, Northern Ireland was called after him. Am I correct in this belief?

Unfortunately we do not hold Robert Ross’ commission papers or service record, but from what I can see from various secondary sources Major-General Ross was indeed born in Ireland, in Rostrevor, in 1766. The town does not appear to have been named after him though, as the etymology predates him. http://www.placenamesni.org/resultdetails.php?entry=15299

[…] The day the White House burned […]

No mention is made of the library books that were burnt. Were they used as kindling or is that a myth? And, did Admiral Sir George Cockburn take a souvenir from Mr. Madison’s desk?