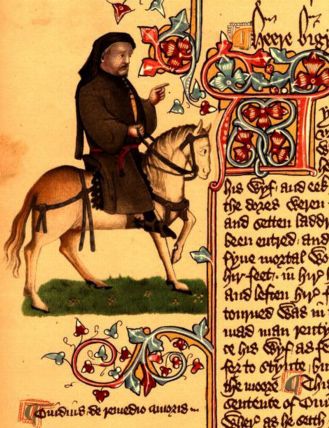

Geoffrey Chaucer as depicted in the Ellesmere Canterbury Tales (source: Wikicommons)

When you think of Geoffrey Chaucer, what words or themes do you think of? Words like ‘writer’, ‘poet’ and ‘philosopher’ come naturally to mind, but what about ‘accountant’, ‘soldier’, ‘politician’ and ‘debtor’?

Those involved in studying Chaucer have long been aware of his extensive career as a courtier, diplomat and civil servant, but the details and extent of his day job haven’t always permeated the public conscience.

While we don’t hold any of Chaucer’s literary works in our collection, we do have hundreds of documents about the man himself and his activities, which allow us to build up a picture of his life and career through the various offices of state that formed the medieval civil service.

Whether counting pennies as a customs officer, fighting the French in the Hundred Years’ War, or in trouble with the central law courts, the people and events featured in our documents all influenced Chaucer in some way, and maybe even provided the inspiration for some of his fictional characters in The Canterbury Tales.

In this series of blogs, I will be exploring just a small selection of these documents to try and give an idea of the man himself, and the circumstances in which he would go on to write his historic works.

Foreign Service

In the first of this series, I will be looking at Chaucer’s early career and involvement in the Hundred Years’ War, as well as his connections to the royal court, showing both the type of activities he took part in and also the gifts and rewards he received for this service.

![Payment to Chaucer by Lionel, earl of Ulster, for carrying letters to England [Catalogue reference: E 101/314/1]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/29165326/chaucer_1_1.jpg)

Payment to Chaucer by Lionel, earl of Ulster, for carrying letters to England. Catalogue ref: E 101/314/1

In October 1360 he was recorded as being in Calais with Ulster, where he was paid three roiales (worth nine shillings) for his efforts in carrying letters to England (datum Galfrido Chaucer per preceptum domini eundo cum litteris in Angliam), although these were probably the earl’s private correspondence rather than state affairs.

Chaucer’s time in France at this point was not as peaceful as a courier job might suggest. Earlier in 1359-60 he had served in at least one of the many military campaigns which formed the Hundred Years’ War, details of which he recorded in a later deposition in the Court of Chivalry (as discussed in a recent blog by my colleague, Ben Trowbridge). In the course of this campaign, Chaucer was captured and ransomed back to the English, for which Edward III had paid £16 (a large sum of money, but one which paled in comparison with the £50 paid for the king’s esquire Richard Stury in the same account).

![Payment of a ransom in Spring 1360. Chaucer’s name can be seen at the end of the fourth and start of the fifth lines [Catalogue reference: E 101/393/11]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/01151022/Ransom.jpg)

Payment of a ransom in Spring 1360. Chaucer’s name can be seen at the end of the fourth and start of the fifth lines. Catalogue ref: E 101/393/11

![Commission to deliver a captured Genoese ship to its rightful master [Catalogue reference: C 76/56 m. 10]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/01151028/Genoese2.jpg)

Commission to deliver a captured Genoese ship to its rightful master. Catalogue ref: C 76/56 m. 10

Trade disputes were not the only European exploits undertaken by Chaucer, however, as he received several commissions throughout the 1370s to travel to Flanders, France and Italy (among other journeys), negotiating peace treaties between England and France and conveying the king’s ‘secret business’ (secretis negociis regis).

![Letters of protection granted to Chaucer on 12 February 1377 to go overseas on the king’s ‘secret business’ [Catalogue reference C 76/60 m. 7]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/29165327/chaucer_1_2.jpg)

Letters of protection granted to Chaucer on 12 February 1377 to go overseas on the king’s ‘secret business’. Catalogue ref: C 76/60 m. 7

The Royal Household

Service in the royal household brought the possibility of significant rewards for both Chaucer and members of his family, as royal favour bestowed gifts of money, goods, and clothes on members of the household regularly.

Alongside Geoffrey Chaucer, we also find evidence for his wife Philippa, who served as domicella to her namesake Queen Philippa between 1366 and 1369 (when the queen died), and continued her service in the household of John of Gaunt into the 1380s.

Some of these issues were paid to Philippa through her husband (per manus eiusdem Galfridi [Chaucer]), whose name features before hers in the roll, but on other occasions she received the sums without Geoffrey’s involvement, including this entry where she received 66s. 8d. as payment for half payment of that term’s annuity[ref]Examples where payment was made via Geoffrey can be found in E 403/459 and E 403/461.[/ref].

![Issue of half payment of annuity to Philippa Chaucer, 2 June 1367 [Catalogue reference: E 403/431]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/01151031/PC.jpg)

Issue of half payment of annuity to Philippa Chaucer, 2 June 1367. Catalogue ref: E 403/431 m. 14

The effects that this quantity of wine may have had on Chaucer’s writings is unknown, but as this warrant and subsequent patent were granted at Windsor Castle on St George’s Day, it has been suggested that the wine may have been a gift to Chaucer in reward for a performance at the annual St George’s Day feast (although such grants were not unheard of to the king’s esquires).

![Royal warrant granting Chaucer the annual gift of a pitcher of wine, to be redeemed from the Port of London [Catalogue reference: C 81/436/30091]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/29165329/chaucer_1_3.jpg)

Royal warrant granting Chaucer the gift of a pitcher of wine, to be redeemed from the Port of London. Catalogue ref: C 81/436/30091

At the funerals of both Queen Philippa in 1369 and Joan, Dowager Princess of Wales (Richard II’s mother) in 1385 the Chaucers received allowances of black cloth for their mourning, alongside the other members of the household.

![Black robes granted to Chaucer as one of those who received livery to mourn the death of the king’s mother (Joan, Dowager Princess of Wales) in September 1385 [Catalogue reference E 101/401/16]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/29165330/chaucer_1_4.jpg)

Black robes granted to Chaucer as one of those who received livery to mourn the death of the king’s mother (Joan, Dowager Princess of Wales) in September 1385. Catalogue ref: E 101/401/16

In 1374, Gaunt granted Geoffrey and Philippa a life annuity of £10 in consideration of their services to John, his mother, and consort, and continued to provide annuities and livery to Chaucer throughout the 1380s and 90s[ref]The National Archives, DL 42/13 f. 90[/ref]. One such gift was a scarlet gown, for which the keeper of Gaunt’s household purchased fur during the financial year 1395-6.

![Purchase of a scarlet gown for Chaucer, 1395-6 [Catalogue reference DL 28/1/5 f. 18d]. Duchy of Lancaster copyright material in The National Archives is reproduced by permission of the Chancellor and Council of the Duchy of Lancaster.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/01151032/Gaunt-robes2.jpg)

Purchase of a scarlet gown for Chaucer, 1395-6. Catalogue ref: DL 28/1/5 f. 18v. Duchy of Lancaster copyright material in The National Archives is reproduced by permission of the Chancellor and Council of the Duchy of Lancaster.

In the next of these blogs, we will dig a little deeper into these appointments, positions and responsibilities, and find out a little more about Geoffrey Chaucer the accountant, customs official, and builder.

Read part two and part three of this series.

Further reading

- ‘The Riverside Chaucer’ ed. Larry D. Benson

- ‘Chaucer Life-Records’ ed. Martin M. Crow and Clair C. Olsen

Very interesting piece, thanks. When Chaucer travelled to Italy, is it known whether he went overland, or by ship?

Hello Dr Friel,

There are unfortunately no known itineraries of the exact route taken to Genoa and Florence, so either option is possible! He was travelling with two Italians, so they may have travelled by ship. Alternatively they may have travelled overland or by river via the Low Countries (presumably avoiding war-torn northern France).

Kind regards,

Dr Euan Roger

[…] This month The National Archive’s Blog has described many of the wonderful manuscripts in their collection, which shed light upon the less familiar features of Geoffrey Chaucer’s life. You can read it on their website or by following this link. […]

Fascinating – thank you for posting! What language are these documents written in? Any in Middle English?

Hello Kathleen,

These documents are primarily written in Latin and Anglo-Norman French, rather than Middle English, as the primary languages of government records for this period. The shift to the use of English in the records of government is a later development.

Kind regards,

Euan

[…] about the real Geoffrey Chaucer? Check out parts one, two, and three of a series on The National Archives’ […]