‘Wall Piece’ by Sarah Kogan

I first saw Rifleman Barnet Griew’s letters and drawings as a very young child at my grandmother Fanny’s house. The resonance of the half-remembered drawings and text from her dead brother’s letters stayed with me, re-emerging decades later when I had become an artist.

As Barney wrote in his last letter to his mother: ‘The chaps told me I was a fool to write home as often as they found it a bad policy – but I know you will understand.’ And write letters home – often three times a day – he did.

I had been working, for around a decade, on a series of abstract canvases concerned with landscape from an aerial perspective and found myself looking at maps and aerial photographs from the First World War. As I was coming to the end of this series, I remembered Uncle Barney’s drawings and sometime in 2011 I opened an old box file in my mother’s house and saw the two piles of papers, squashed together with perished rubber bands. I sat down on my living room carpet and started laying everything out in chronological order, something I repeated for my digital video, ‘Carpet Piece’, which you can see in the exhibition.

At that point, I knew very little about Barney, but as I laid out the 180 illustrated letters, photographs and photographic postcards, sent over a period of only five months, I discovered that he had lived and worked in the family furniture business very close to my studio. This building was formerly used to make the tents for the First World War, and as I subsequently discovered, overlooks the same canal where my grandmother collected the timber off the barges to send to the family furniture manufactory. It was at this point I also discovered that Barney had trained as a mapmaker and scout. This strangely mirrored what I was doing in crawling over the floor with his correspondence and also with my paintings that were about the landscape as seen from above. I remember thinking that the centenary of the Battle of the Somme was very close and that perhaps it might be possible to get funding to follow Barney’s footsteps back to the Somme and visit the locations that appeared in the photographic postcards. The project was subsequently supported by public funds from The National Lottery through Arts Council England.

‘Carpet Piece’ by Sarah Kogan

The next step was to approach The National Archives, which holds the British Army war diaries. There, I arranged to meet William Spencer, the Principal Military Specialist. William told me that he believed the archive was ‘unique’. He said that privates were not allowed to keep diaries in Barney’s regiment and that they almost always chose not to reveal what was happening to them on the front line to spare their families. However, Barney wrote multiple letters to his sister Fanny, to his brother Isaac and to his parents Solomon and Rebecca. This alternative view of the run-up to the Battle of the Somme is very unusual and allows us access to his private thoughts and feelings. You see this in correspondence from officers, but rarely from privates. In a sense, the letters remind us of modern day tweets – continually asserting the fact that Barney is still alive and helping to maintain his emotional connection with home.

I asked William how close he could get me to where Barney had stood and he replied, ‘within a metre’. He then gave me a list of war diary references, which enabled me to trace Barney’s journey to France. Barney and the Jewish volunteers from Hackney had been stationed in Yiddish street trench (named by the military) which ran along a road which still exists, so I could work out where he was likely to have fallen – even though his body was never found.

In trying to uncover more about Barney’s last months, I undertook two research trips with my partner Jeremy Bubb (a filmmaker) to France, to stay in a former First World War billet. Those visits were the basis for what is presented in the exhibition, including Jeremy’s digital video installation, ‘Palimpsest’. During our stay we were shown many sites of hidden history; I went to France to trace Barney’s journey leading up to his death but also discovered a contemporary story of my relationship with descendants of the people who billeted British troops during the First World War. The exhibition seeks to tell both those stories from my perspective as an artist.

Sarah Kogan in Gommecourt, 2014

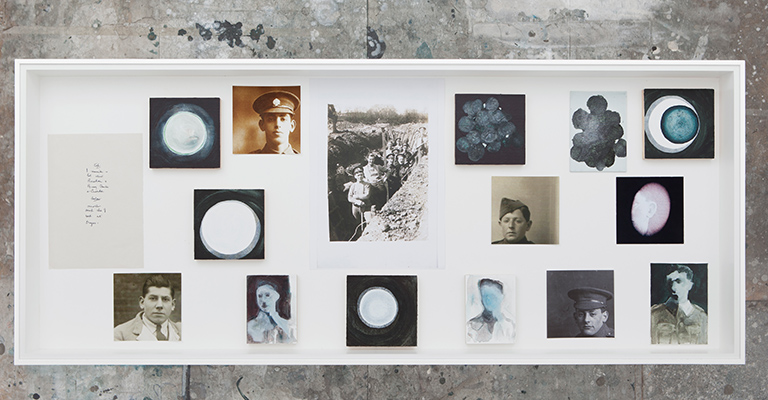

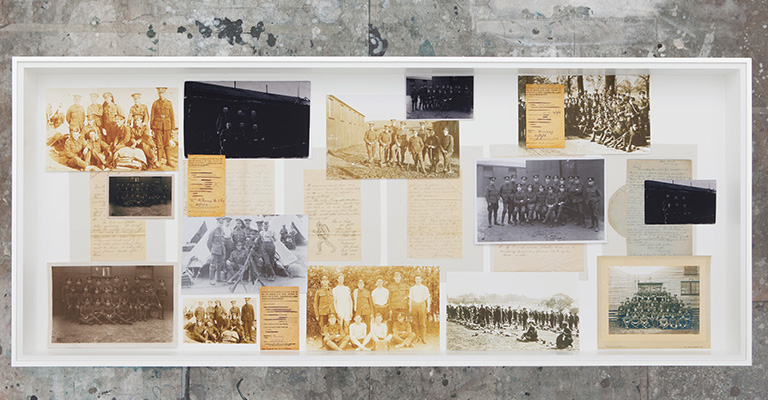

This show is unique in that it is the first ever contemporary art show at The National Archives. I decided to show all the work in 14 purpose-built display cases in order to explore ideas of archiving the contemporary and to display everything from the aerial perspective. In addition, the cases carry with them a coffin-like association and also that of markers in war cemetery. They include items and extracts of text from Barney’s unpublished archive, artworks that I have generated or found in response to his archive and material from The National Archives.

Changing the Landscape exhibition at The National Archives

I have also included in the exhibition a rarely seen 2.8 metre-long panoramic photograph from The National Archives’ collection, which was taken in Gommecourt on the day Barney arrived in May 1916. The photograph was shot from inside the trench in which Barney was stationed, looking out over the field where he died. We stand looking at the field as if we are Barney. There are no figures before us, but we are aware that hundreds of men, preparing for battle, would have been behind the photographer. It is the closest we can get to standing in their shoes and I have included copies of Barney’s letters written from this trench which talk about both the fatalities – together with the insignificant details – of those days in May 1916, six weeks before the beginning of the Battle of the Somme.

Table 2: ‘I remember’, from Changing the Landscape

Table 3: ‘Looking for Barney’, from Changing the Landscape

Changing the Landscape is on display in the first floor reading rooms until 17 September. Artist Sarah Kogan will also be leading a practical art workshop for adults, Drawing from the archives, on Thursday 9 June.

Dear Sarah,

So many thanks for this commentary. Of course I knew about Uncle Barny, and of the grief his (initially presumed) death caused to his parents and siblings. My Dad was 8 when Barny died, but still spoke of him almost as if he were still alive. Barny was of course the second oldest of the family while my father, David, was the youngest. To learn so much more about him makes it seem as if I knew him in reality.

Much love,

Antony