T 1/12400/45841. Image of a letter calling for the descendant of a former Prime Minister to be spared the workhouse.

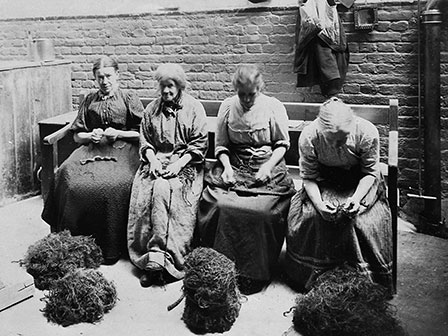

You may have seen the recent BBC1 television programme, 24 Hours in the Past, which sent six celebrities off to spend some time working in Victorian England. One of their ‘placements’ was the workhouse, an institution that was feared by the working classes. The celebrities endured the painstaking tasks of breaking bones and picking oakum. While today we enjoy seeing celebrities suffer with little food and harsh working conditions, in 1919 politicians were keen for those with an illustrious background to avoid such a fall from grace.

From T 1/12400/45841 we can see that John Wells Wainwright Hopkins, Conservative MP for St Pancras South East, stated in 1919 that ‘the direct descendant of a Prime Minister of England should not under these circumstances be permitted to drift into the workhouse.’

The descendant that Hopkins is referring to is Miss Emma Augusta Perceval the great-grand-daughter of Spencer Perceval, Prime Minister from 1809 to his assassination in 1812, and her circumstances were thus:

- her father, a former police inspector in India, was murdered on the underground in 1880 which was suspected to be an act of Irish political revenge

- she was apprenticed as a mantle machinist and supported her mother until her death in 1916

- after her mother died she became ill and had ‘several operations and much bronchitis’

- the Charity Organisation Society funded her to go to a convalescent hospital but her sight was deteriorating and there was little prospect of her being able to work again

- at the age of 50, with only two elderly aunts not in a position to help, the workhouse was a real possibility

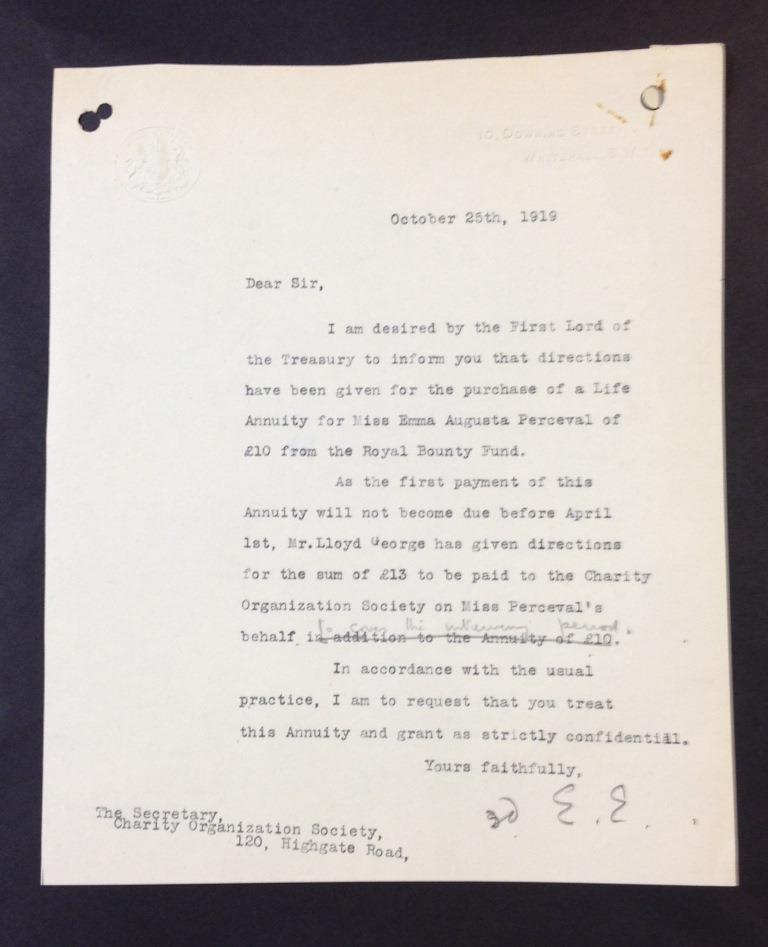

T 1/12400/45841. Warning by the Prime Minister’s Private Secretary that the grant to Miss Perceval should be treated as ‘strictly confidential’.

Perceval’s circumstances counted in her favour. In late October 1919 Emma was granted £13 by the Charity Organisation Society to tide her over until the following April, when she was due to start receiving a £10 life annuity which cost the Royal Bounty Fund £137 to set up. This however was not what Hopkins had been hoping to award Emma with; initially he had tried to get her a civil list pension, something that she was not eligible for. While the correspondence does not state this explicitly, it is likely that she was not eligible as she had not served the crown, government or the public.

The grant that she received from the Royal Bounty Fund means that she was one of the privileged few (or potentially thousands) whose case was considered by the serving Prime Minister. It was his office’s decision to give her an income for the rest of her life. The fund was also shrouded in secrecy which can be seen in a warning issued by Captain Ernest Evans (Private Secretary to the Prime Minister) that, as usual, the assistance should be treated as ‘strictly confidential’.

Despite the discreet nature of the Royal Bounty Fund there are many mentions of the grants that it administered within our catalogue, Discovery. Well-respected artists and scientists were awarded grants as were the widows of ethnologists, Antarctic explorers and the widow of the page to Queen Victoria.

The case of Miss Perceval however shows that in 1919 there was still a great stigma associated with the workhouse. Those in power could not comprehend that the descendant of a Prime Minister, one of their own, could fall on hard enough times to enter the workhouse. It was still reserved for the poorest of the poor, not the political class; therefore all was done to ensure that Miss Perceval was spared the task of picking oakum. Unfortunately these ladies were not spared the same.

Nice to see a mention of Treasury files. Unfortunately such cases, even of those with well-known ancestors, including the relatives of David Livingstone who were living in poverty, was not unknown.

Great blog which gives us an intriguing insight into contemporary attitudes towards workhouses and social class!

The specific story behind this Treasury document is even more intriguing than at first appears. Public disquiet at a direct descendant of Spencer Perceval being destitute may have been heightened because, after his assassination, Parliament voted the Perceval children a vast sum of money to support them – £50,000 (worth about £1.7 million in today’s money).

So why was Miss Emma Augusta Perceval not still benefitting from that gift in 1919? It was quite simply because she wasn’t actually the Prime Minister’s great granddaughter at all. I researched this case a number of years ago, as I’m distantly related to Spencer Perceval’s wife, but found that Emma’s father had no clear relationship to that family. His marriage certificate (21 September 1865, St Jude’s, St Pancras, Middlesex: Kirwan Joyce Perceval to Augusta Clarke) states that his father was Richard Perceval, gentleman, but Spencer Perceval had no son of that name. The 1871 census records that Kirwan was born in Rome, but I have found no birth record for him.

Whether Emma knew that she was not a direct descendant of Spencer is a mystery. It seems as though the family were prone to embroidering stories; the father’s death at the hands of the Fenians does not bear much probing either. His unconscious body was found on the tracks at Temple station with his inside pockets turned out but £18 in his outer pockets. He died shortly afterwards and the Coroner returned an open verdict. The editor of the Illustrated Police News posited that he was thrown from the train following a bungled robbery attempt. Although his career in the Cairo Police was mentioned, none of the newspapers reporting on the mystery mentioned that the victim was the grandson of Spencer Perceval – further evidence that there was no close relationship.

What is particularly interesting is that no civil servant seems to have tested Emma’s story. The secrecy surrounding the award of a pension probably prevented other family members coming forward to disprove her claim.

Thank you both for your comments.

Ruth – yes it is particularly interesting that Emma’s story wasn’t tested before she was granted assistance by the Royal Bounty Fund; it certainly adds some intrigue to the file and her case. As you say, Emma may have been innocent in claiming to descend from a former Prime Minister. Yet, if not, it shows the length that people went to in order to avoid the conditions of the workhouse.

[…] her blog post, archivist Katie Fox writes about Emma Augusta Perceval, a woman who claimed to be the […]