Special codes, wiretapping, and secret communication devices disguised as flag poles: this all sounds rather like James Bond, but in fact it describes the intelligence network set up in the Mediterranean to support the Royal Navy at the turn of the 20th century.

CO 1069/716 Valletta Harbour, Malta, home of the Mediterranean Fleet

Intelligence is vital to any form of military endeavour and the Victorian Royal Navy developed an ad hoc system of gathering information. Developments in technology and strategy over the course of the 19th century meant that this became increasingly outdated. In the late 1880s, the British government grew concerned that the Russians might launch a surprise attack on Constantinople, capital of the Ottoman Empire. This had been a key target for Russian expansion for decades and there was a belief in London that they might mount an amphibious attack on the city. To pre-empt any such attack the British needed advanced and accurate intelligence.

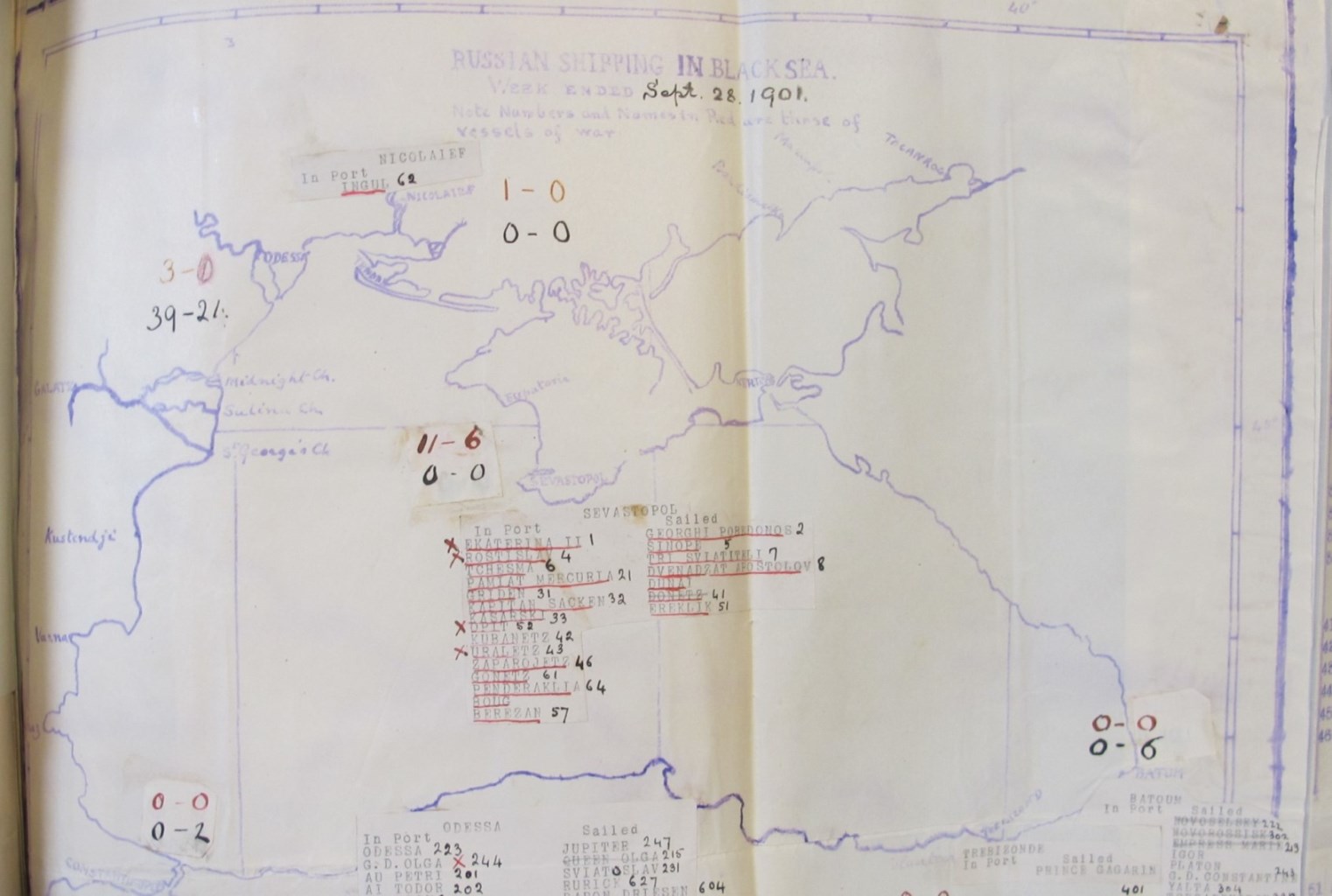

To collect this the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, personally drove the establishment of a ‘ship watching network’ in the Black Sea ports. British consuls in these ports were recruited to monitor any movements of Russian warships and report these by telegraph back to Britain. These messages were sent in cypher, with a special cypher to be used in case of emergency. This represented a new departure in creating a formal structure for collecting naval intelligence, and institutionalised the use of consuls in this role. It was, however, largely restricted to the Black Sea. (FO 95/775)

FO 95/775 A return of the Black Sea ship watching network

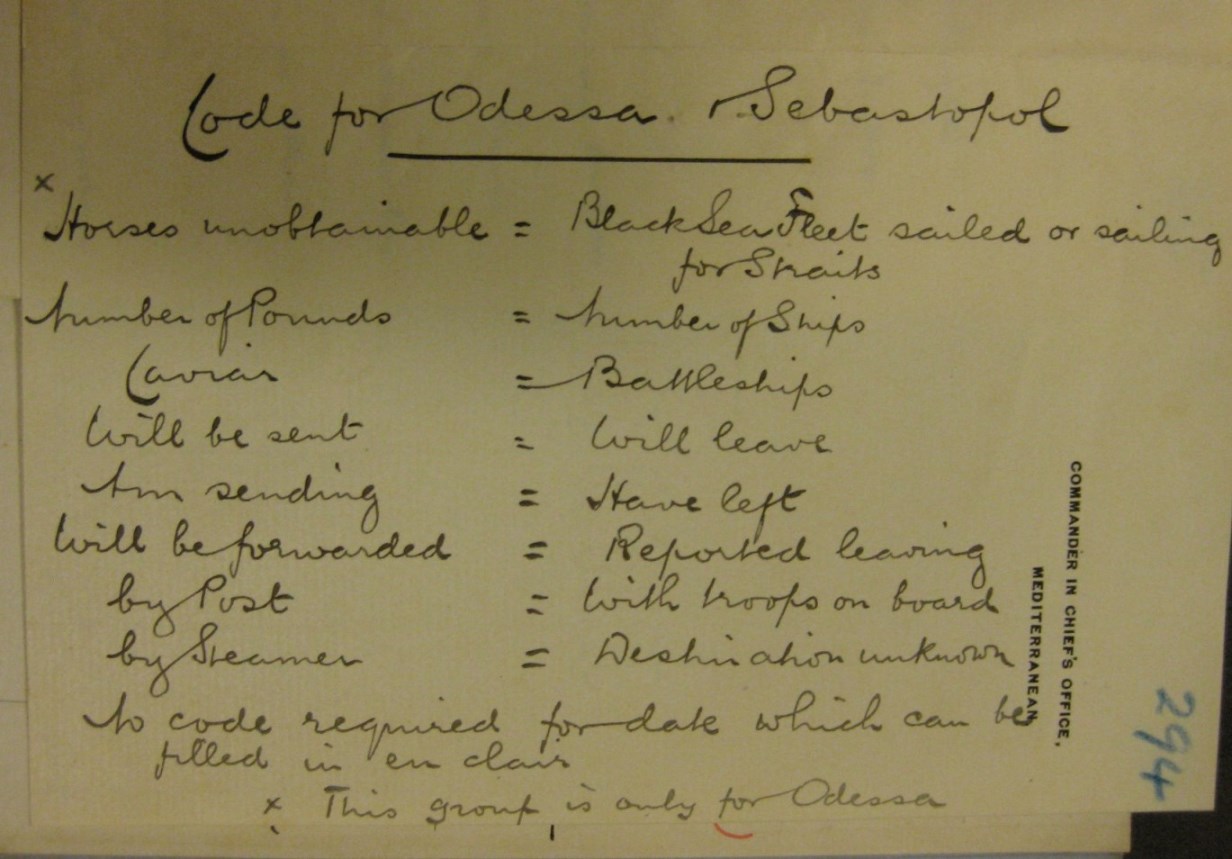

In 1900, Vice-Admiral Sir John (Jackie) Fisher took command of the British Mediterranean Fleet. Fisher had a reputation as a radical reformer and this immediately fed through into intelligence. He quickly pressed the Foreign Office into allowing the British consuls in the Mediterranean to telegraph him movements of foreign warships; he also built relations with certain consuls who provided further intelligence. Fisher worked with the British Ambassador in Constantinople, Sir Nicholas O’Conor, to devise a means of getting intelligence from the Black Sea to Malta as quickly as possible. Knowing that the Russians carefully monitored telegraph communications and would block any messages sent in cypher, O’Conor and Fisher developed their own code. This had a number of bizarre substitutions: a message reading ‘horses unobtainable’ meant that the Black Sea Fleet had sailed, while ‘caviar’ was used as code for battleships. (ADM 121/73)

ADM 121/73 Fisher and O’Conor’s secret code

One location which particularly concerned Fisher was the island of Syra (modern day Syros): it occupied a key location in the Aegean on the route to the Dardanelles and also happened to be ‘the telegraphic centre of the Eastern Mediterranean’. The British consul at Syra, William Cottrell, was also the Eastern Telegraph Company manger on the island and so had access to all the information flowing across the Mediterranean to Constantinople. Cottrell was heavily involved in the collection of naval intelligence including through a network of ‘friends’ inside the Ottoman Empire. A serious concern for both Cottrell and Fisher was Russian influence over the Ottoman telegraph system and especially the risk that they would use this to prevent crucial information getting from the British Embassy in Constantinople to the Mediterranean Fleet in times of strained relations. To get around this problem Cottrell, working with Captain Ian MacKenzie Fraser, developed a system to transmit messages direct from Constantinople to Syra, bypassing the Ottoman authorities.

This just left the step of passing the information from Cottrell to Fisher. In order not to raise suspicion, the regular presence of British warships at Syra was undesirable, so instead Cottrell proposed an ingenious solution. He decided to erect a flagstaff in the grounds of the consulate – supposedly ‘for the purpose of hoisting the Union-Jack on Fête days’. In fact the flagstaff was to act as a wireless telegraph mast with the cables leading into the consulate. By this means Cottrell would be ‘able to communicate direct with a ship 70 miles off with absolute secrecy, he alone receiving and transmitting messages from the Privacy of his bedroom.’ Fisher was extremely keen on this plan, but London was less certain. There was considerable debate, and it is unclear if Cottrell’s flagstaff was ever erected. Fisher did, however, mange to persuade London to provide Cottrell with a considerable additional allowance to facilitate his work. (ADM 121/73)

The eastern Mediterranean was not the only area of interest to the Royal Navy, with the French fleet still being seen as Britain’s primary rival. To gather intelligence on the French, Fisher cultivated Martyn Gurney, the Consul General at Marseilles. The admiral admired Gurney’s ‘great zeal, ability, activity and great knowledge of naval matters which he has been improving ever since he was Vice Consul at Spezia: [he] is the person on whom I place my chief reliance for early information.’ Such was Gurney’s importance to Fisher’s intelligence system that the admiral later nominated him for a knighthood. (HD 3/128, FO 1093/110/1)

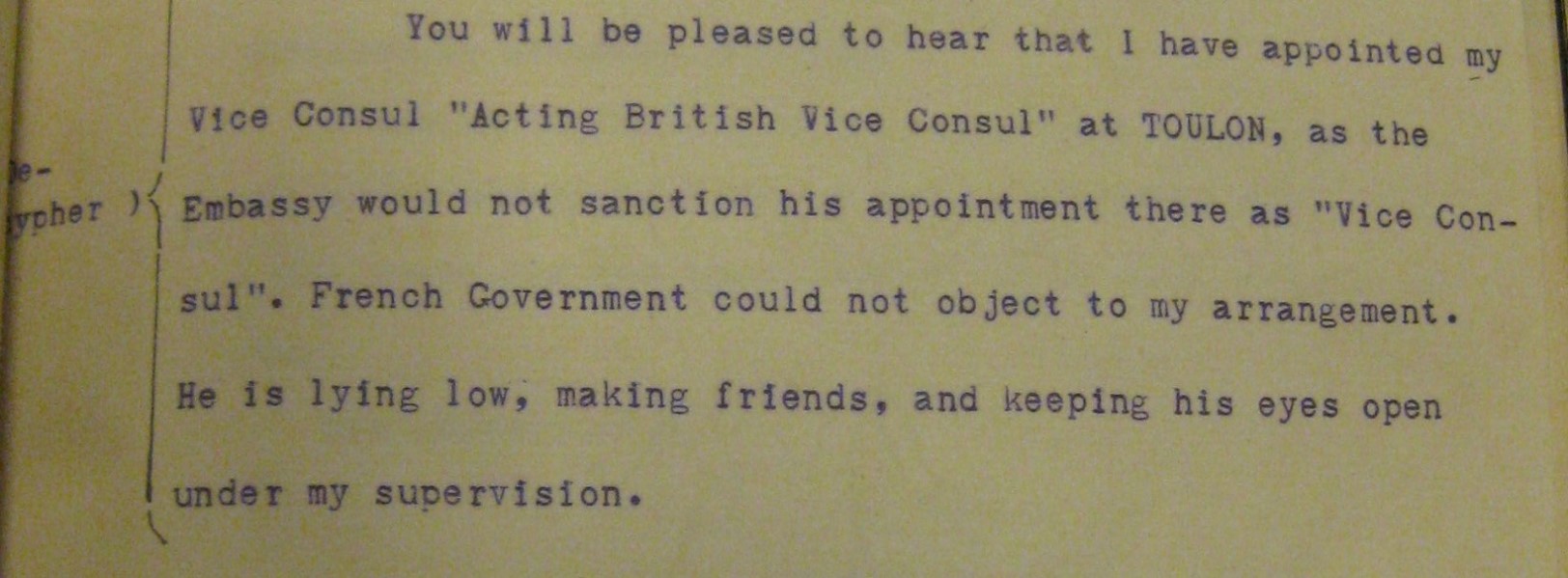

In 1900, Gurney appointed Norman Haag as acting Vice-Consul at the naval port of Toulon to assist his efforts. As he reported to Fisher, Haag was ‘lying low, making friends and keeping his eyes open under [his] supervision’. This clearly worked, as Haag was soon receiving an allowance from the Secret Service Vote and transmitting intelligence to the Admiralty. Much of this was what would now be described as open source intelligence, but it is clear that Haag also crossed over into actual espionage. For example, in 1902 he provided a report on French submarine construction including a ‘confidential pamphlet containing much interesting information’. (ADM 121/73, ADM 1/7604)

ADM 121/73 Haag’s appointment to Toulon

By 1906 the diplomatic situation had changed, and Germany had replaced France and Russia as Britain’s primary naval rival. Fisher, by this point First Sea Lord, quickly redirected the intelligence system he had developed in the Mediterranean onto the new target. Haag was once again at the centre of this, being shifted to the consulate at Bremerhaven. This network proved highly effective at gathering intelligence, and parts of it were incorporated into the newly formed Secret Intelligence Service from 1909. 1

Notes:

- Richard Dunley (2014) ‘Not Intended to Act as Spies’: The Consular Intelligence Service in Denmark and Germany 1906–14, The International History Review ↩