Inspired by a recent team visit to Bruges as a place of historical interest, and out of curiosity as to the depths of our records, we decided to investigate what we could find out about Bruges and Belgium using records held here at The National Archives. Many of the results from a simple Discovery search (using the keyword ‘Bruges’) came up with records related to looting of art by the Nazis in the Second World War. Of all of the war crimes committed by the Nazis during the Second World War, looting and plunder of cultural property in occupied territory was not something we were all too familiar with – so we decided to investigate this further. What items were looted? Why? What happened to looted and plundered items from occupied territories, such as Belgium? Could the records held here answer these questions for us?

What items were looted and why?

The Nazis, and Hitler in particular, greatly admired and respected art and culture (provided they were by non-Jewish artists and not what they termed ‘degenerate’ art). Looting therefore was intended for the ‘moral and material enrichment’ of the German people and of particular party leaders through the attainment of iconic art works in occupied territories, including Belgium (FO/371/45769/6). It was also for the purpose of Hitler’s personal ambition of establishing the finest museum of art in the world in Linz (T209/29/15).

Michelangelo’s ‘Madonna and Child’ monument, looted by the Nazis from the Church of Notre Dame in 1944. Courtesy of Christine Peters.

Towards the end of the war, and an Allied victory was assured, Britain set up a Committee for the Preservation and Restitution of Works of Art, Archives and Other Materials in Enemy Hands, also known as the Macmillan Committee. The American equivalent to the Macmillan Committee was the Roberts Commission, named after its Chairman, Supreme Court Judge Justice Roberts. After the Allies had entered Europe – along with the Soviets – they established the Restitution Commission whose objectives were: recording what was taken by the Nazis, identifying what had been found and returning it to its rightful owners (FO 371/45769).

One of the cases dealt with by the Restitution Commission involved Michelangelo’s ‘Madonna and Child’ statue, a fifteenth-century monument, looted in 1944 from the Church of Notre Dame in Bruges (and from where our curiosity first stemmed). According to a report by the Macmillan Committee, the statue was taken by:

‘two German officers…accompanied by a party of armed sailors [who removed] the statue in order to protect it from the approaching Americans. By light of torches, the visitors loaded the statue, wrapped in a number of mattresses, on to a waiting lorry.’ (T209/12)

This conjures up an incredible image of the removal of one of Belgium’s most treasured – and priceless – monuments on the night of 7 September 1944. We were keen to trace more information on this, and what else the documents could unveil about its journey.

What happened to looted art?

War Office Military Headquarters files (WO 204) and also the files of the Directorate of Civil Affairs of occupied enemy territories (WO 220) from during the Allied advance contain many reports of the intelligence that was being collected about missing items, when they were taken, by whom and their suspected locations. A lot of the collected information was speculative, but nonetheless this was fed back to the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) who analysed the information and coordinated the recovery of the items.

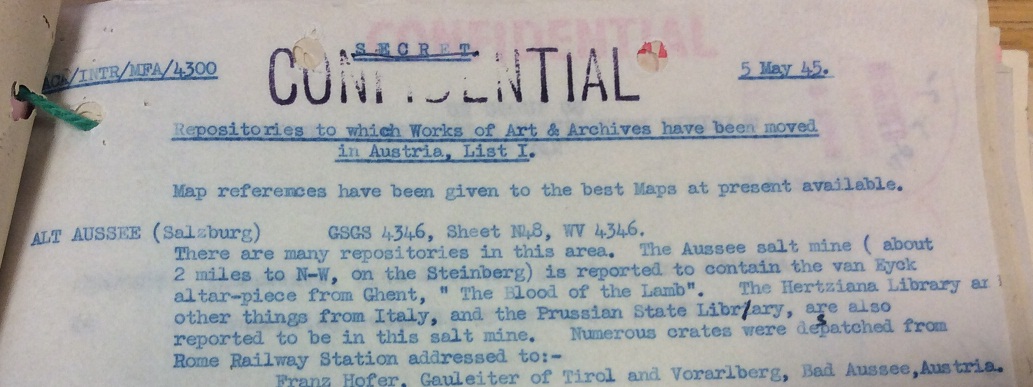

The Nazis, it seemed, had been storing looted items in various locations across Austria and Germany from salt mines to castles. Furthermore, a report dated May 1945 named the Austrian mountains as the supposed location for a large number of repositories containing stolen artwork. This information was supported by reports from Rome of numerous crates containing valuable Italian documents and artefacts which were despatched from Rome railway station to Altaussee in the Austrian Mountains (WO 204/3043).

War Office intelligence report about the suspected location of Nazi repositories, catalogue reference: WO 204/3043.

Whilst the people of the town were most likely still feeling the effects of the fighting and hardships of war, the US Army reached hundreds of priceless monuments and artworks, along with Micehelangelo’s Madonna and Child statue, hidden in an unsuspecting salt mine beneath the town of Altaussee, ending Hitler’s ambition of a Führermuseum.

Did the items get returned?

The responsibility for the recovery and documentation of the rediscovered art fell heavily on the armed forces, the army being the first into the formerly Nazi occupied territories. In order for the army to be capable of carrying out the necessary work of recovering looted materials, they were accompanied ‘by specialists in the fine arts, familiar with the descriptions of works of art and of cultural monuments in Europe’ (Foreign Relations of the United States, 1944 Vol I).

If you have seen the George Clooney film The Monuments Men, it was the story of these individuals that the film was based on. Their job was:

‘to collect information about works of art and other cultural materials which have been plundered by the Axis powers or their forces; to locate and secure them for eventual restitution; and to collect information about the personnel that have been responsible for such plundering’ (WO 204/3043).

In order to manage the task of returning everything that had been recovered, the Allied forces transferred everything they found to a central sorting point in Munich so that the Restitution Commission could begin arranging the return of these looted works.

Discussions between Britain and America illustrate how it was decided early on that the only feasible way to administer the return of the items would be to deal with governments, who were keen to have their items returned to them as soon as possible. Many of these items were returned promptly, including the statue of the Madonna and Child, which is now on display in its rightful home in Bruges today.

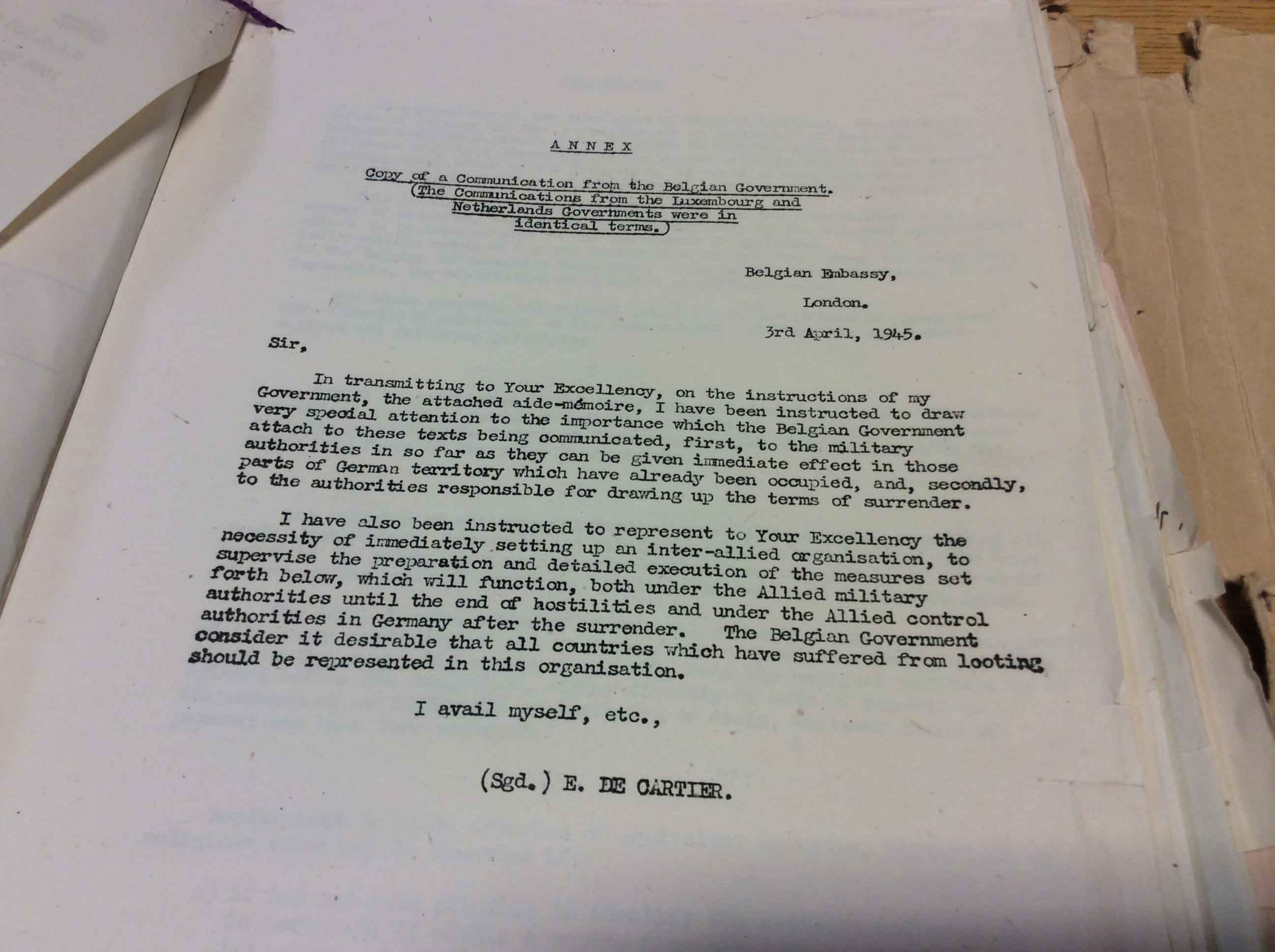

Letter from the Belgian Embassy requesting their representation within a committee to ensure the return of looted items (catalogue reference: FO 371/45769).

Many however have still not been returned. For example, there was a recent discovery of 1,300 works of art in Munich, many of which were looted by Nazis. The large number of items that remain unaccounted for are a reflection of the size of the task that the Allied commissions undertook, a task which, given the sheer size, should be considered a huge success.

The records held here at The National Archives show the level of planning and effort that the British and American governments put into the recovery of Europe’s cultural heritage, reflecting the importance they placed on it. A selection of these records can now be accessed online via our online catalogue, Discovery, thanks to a digitisation project focusing on Nazi era cultural property. Guidance on researching them can be found in our research guide on Looted Art 1939-61.

Most places in Belgium have two names/spellings and other records for Bruges can be found under ‘Brugge’.

We know that works of Art were taken from my husband’s father’s family in Prague and possibly Attersee in Austria. We don’t know what they were and there is nobody left alive who would know. Were any records kept of families who lost their paintings etc.

Hi Sarah,

Unfotunately The National Archives is not the best place to look for information on items looted from individual families by the Nazis. I suggest you contact the Commission for Looted Art in Europe. They should be able to offer you advice. I hope this is helpful.

Thanks,

Chrissy.