While going through private correspondence of Lord Curzon, the British Foreign Secretary from 1919 to 1924, a couple of letters jumped out at me. These were written by prisoners of war to their families and had been forwarded on to the King in a desperate plea for help. The truly remarkable part of the story is that these men were not held by the Germans, but by the new Bolshevik regime in Russia; collateral damage in Britain’s secret naval war with the Soviets.

These letters, written by two young men to their fathers, give an extraordinary personal perspective on this forgotten aspect of British military history.

Coastal Motor Boat © IWM (Q 20636)

Following the Bolshevik revolution in Russia the country rapidly descended into a civil war, with Britain and other Allied powers offering economic and military support to the Estonians and White Russians who were fighting the ‘Red’ Bolsheviks.

Following the end of the First World War Britain stepped up its support to include a naval force in the Baltic. The Bolsheviks had captured the old Tsarist navy including two powerful battleships, which threatened the British forces and their White Russian allies. As such the British commander, Rear-Admiral Sir Walter Cowan, planned a daring attack on the Bolshevik ships in harbour using Coastal Motor Boats (CMBs), fast lightweight craft armed with torpedoes.

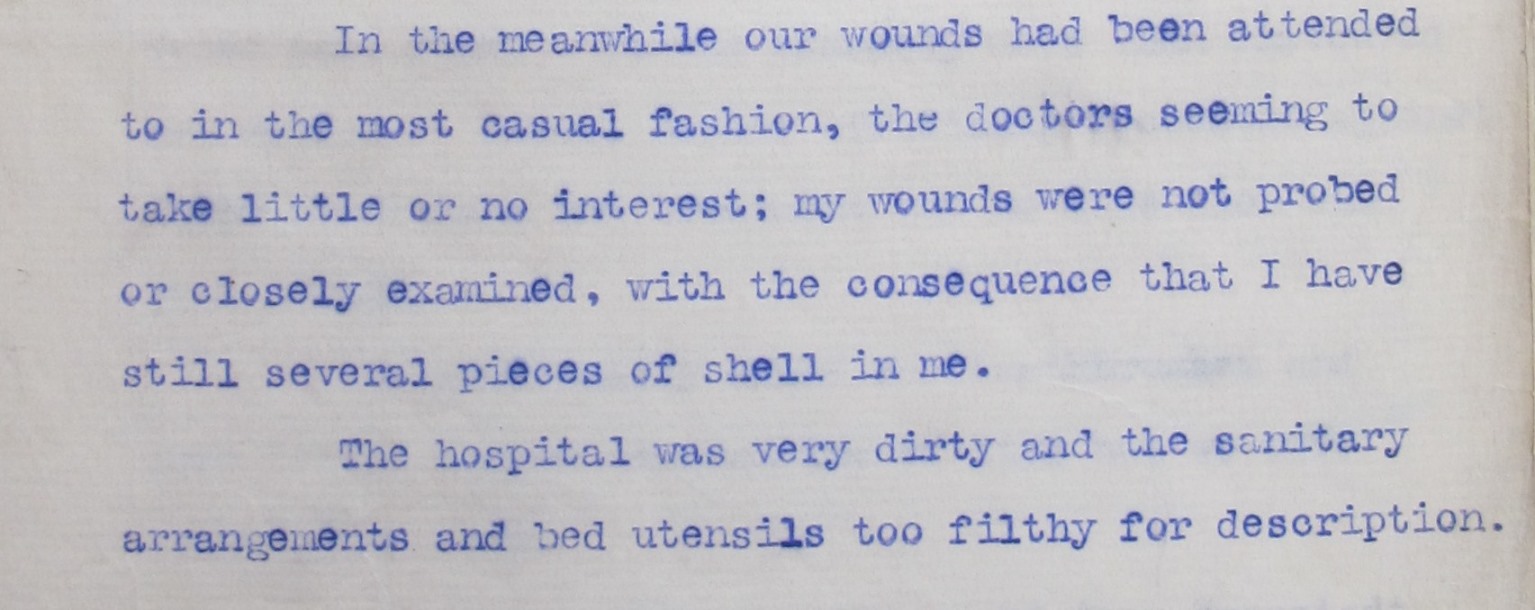

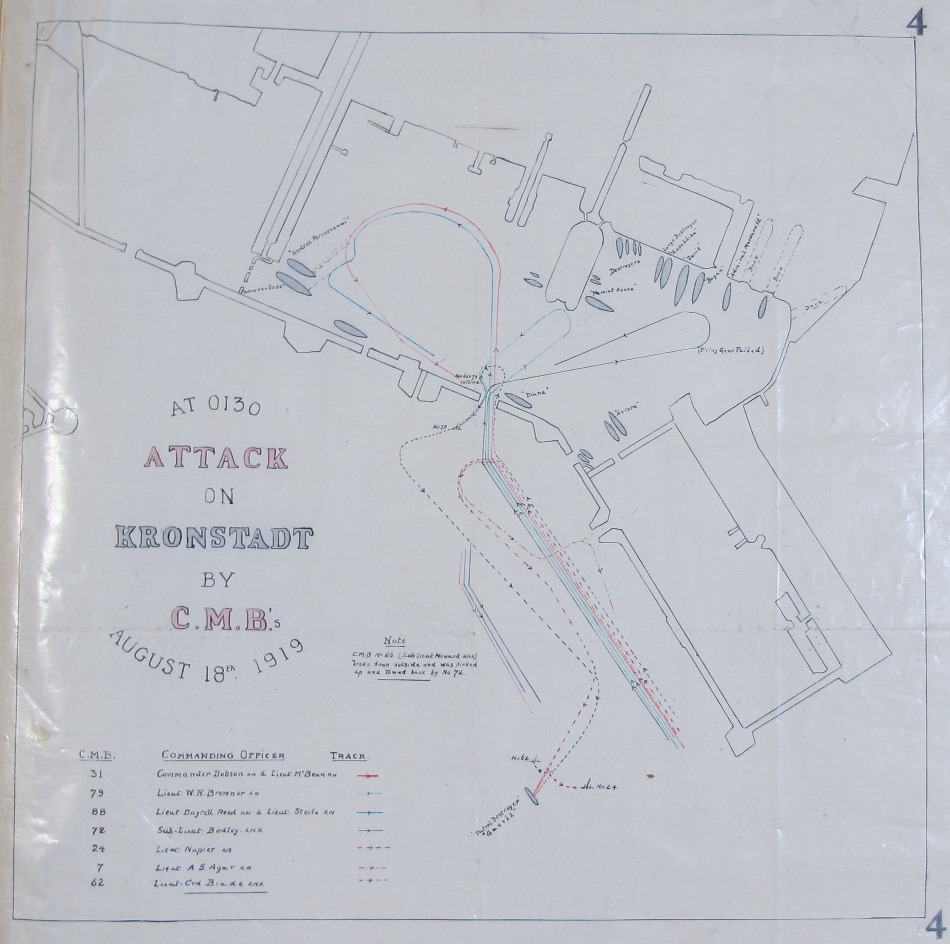

Early in the morning of 18 August 1919 seven CMBs began a high speed run past the forts protecting the Russian harbour at Kronstadt. Under the cover of darkness the boats successfully penetrated the harbour and delivered their deadly cargo. The attack was claimed as a spectacular success with the British believing that both of the Soviet battleships and a depot ship had been sunk. In reality the damage, although serious, was more limited. Admiral Charles Madden, Commander of the Atlantic Fleet, however declared that ‘this successful enterprise will rank among the most daring and skilfully executed of the naval operations of the war. On no other occasion has so small a force inflicted so much damage on the enemy’ (ADM 137/1679).

This did, however, come at a cost. Despite the initial surprise the Bolsheviks quickly responded and opened fire on the retreating CMBs. Three of the boats were sunk, killing three officers and nine other ranks, while three officers and six men were captured. Among them were Lieutenant William ‘Bill’ Bremner, commanding CMB 79 and Sub-Lieutenant Osman ‘Tony’ Giddy, second in command of CMB 24.

Report on the action (catalogue reference: ADM 137/1679)

Communications between the British and the Bolsheviks were virtually nonexistent, and the captured men were initially reported as killed in action. The men’s families eventually heard that they were alive and being held prisoner. In November they were allowed to send personal letters by the Soviet authorities, but these would have brought scant comfort to the families. Giddy wrote to his father say ‘how absolutely imperative it is for an exchange [of prisoners] to be made before the winter gets any worse – for reasons which are obvious’. He continued that ‘the blockade wont let them feed us, and it’s a matter of life and death that these [prisoner] negotiations prove successful very soon’.

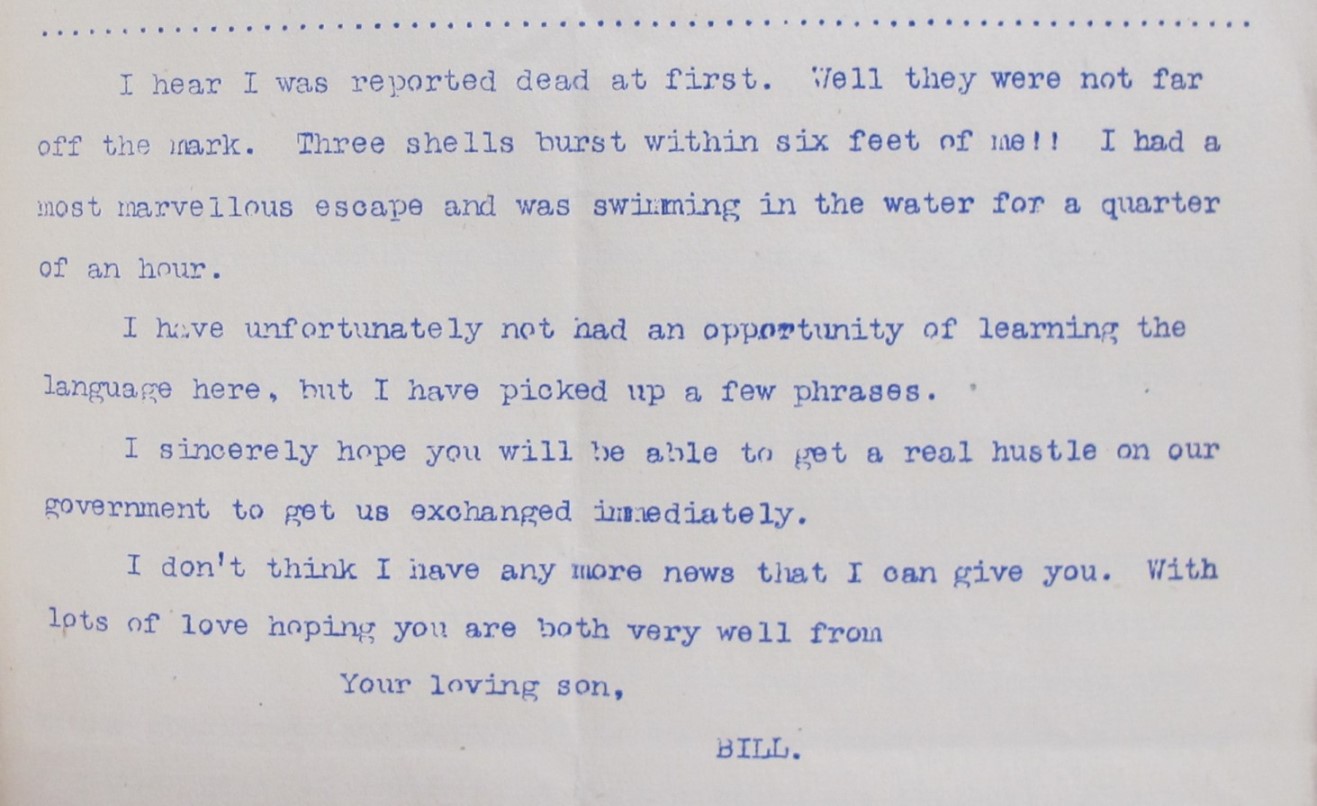

Bremner’s report on captivity (catalogue reference: ADM 137/1679)

Bremner’s letter provides an amazing example of understatement. He begins positively noting ‘I have got a cold but am otherwise in good health’. He then goes on to confess that:

‘the wound in my left thigh, near the groin is not yet quite healed & causes me a good deal of inconvenience and I have still splinters in my left thigh, about half way down, in my left wrist, and in my face, so I cant walk about and do things, but have to lie up rather and keep still. I have been trying to get into hospital for the last 3 weeks in fact ever since I left the Hospital in Petrograd in order to have them taken out…. They could not operate on me at Petrograd as I had erisipelas of the wound in my left thigh and nearly kicked the bucket’.

Both letters hint at the personal anguish caused by the capture of the men, with Bremner closing his letter ‘with lots of love hoping you are both well, from your loving son. Bill’. Giddy wrote in a similar style, ending ‘let’s hope we have a proper Christmas all together this time.’ He was to be disappointed (FO 800/157/12, FO 371/3944).

Bremner’s letter to his parents (catalogue reference: FO 371/3944)

Unsurprisingly both families were extremely upset on receipt of the letters and sought to do everything possible to get their sons released. Giddy’s father wrote imploringly to his local MP:

‘I cannot think that any Englishman, who was aware of the horrible death from starvation and cold which awaits these fellow country men… would not try and bring pressure to bear to obtain their release.’ (FO 371/3944)

Donald Bremner, Bill’s father, used his position as Assistant Commissioner of the City of London Police to get an interview at the Palace, taking copies of the letters. The King was clearly moved by the plight of the men and requested that Curzon ‘do everything in your power to try and deliver these and the other prisoners from their present very dangerous position’.

The pressure had some effect and prisoners began to be released. Bremner was released ‘unexpectedly’ on 30 January 1920, seemingly on account of his continued ill health (FO 371/3945). Giddy, however, remained a captive throughout the harsh winter and was not even released in the main batch of prisoners in March 1920. His family were, by this point, becoming desperate. His father wrote to the Foreign Office

‘We are very troubled by a telegram received from Lady Marling at Helsingfors [Helsinki]. It states that Lieut Napier RN has arrived at Terijoki, and goes on to say “Giddy held back with remaining officers”. Why “held back”?’

The Foreign Office were equally frustrated, with one official minuting ‘it is clear that the Soviet Govt are not loyally carrying out the agreement, or even telling the truth’. Eventually the Bolsheviks gave way, and Giddy was released on 15th April 1920. (FO 371/4043)

The return of these men and the gradual withdrawal of British support for the anti-Bolshevik forces saw the issue slip from view. The Anglo-Soviet conflict has been almost entirely forgotten, overshadowed by the other tragic events of this tumultuous period. These personal letters, hidden away in official correspondence, provide an insight into these events and serve as a poignant reminder of the human impact of such conflicts.

In Baltic Episode: A classic of secret service in Russian waters (1963) Augustus Agar records the infiltration of agents into Russia from Finland and the attack on the Russian warships. He implied that the decision to attack was his and not ordered.

Are there any good books which cover the Anglo-Soviet conflict? Two members of my family were involved. My grandfather fought in the force that went to Archangel and my Gt Uncle was interned by the Bolsheviks in Odessa.

Is the author aware of the papers of Douglas Young held by the university of Leeds (I believe).He was British consul based in archangel at the time. My father befriended him in South Africa where he lived in retirement. Andrew Rothstein drew extensively for his book covering the same topic as your article. You may find some interesting and source material for your research here.