Iraq has very much been in the news lately. Overwhelmed with the war stories, you may have missed the very uplifting news of the opening of a museum in Basra, in one of Saddam Hussein’s old palaces. The museum gathers artefacts relating to the history of the city since the Hellenistic period, and is a fantastic place. This took me back to the 1920s and the opening of another museum…

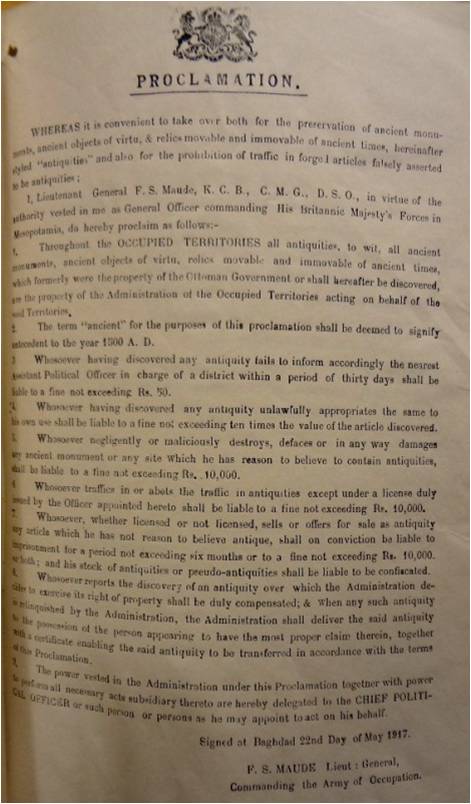

General Maude’s Proclamation, 22 May 1917 (catalogue reference: FO 371/3410)

You may think that, during the First World War and in its immediate aftermath, archaeology wasn’t very high on the agenda. You would be wrong.

Shortly after capturing Baghdad in 1917, General Maude issued a proclamation to regulate the preservation of archaeological sites and the antiquities trade, and promised high penalties to anyone desecrating an ancient monument (FO 371/3410).

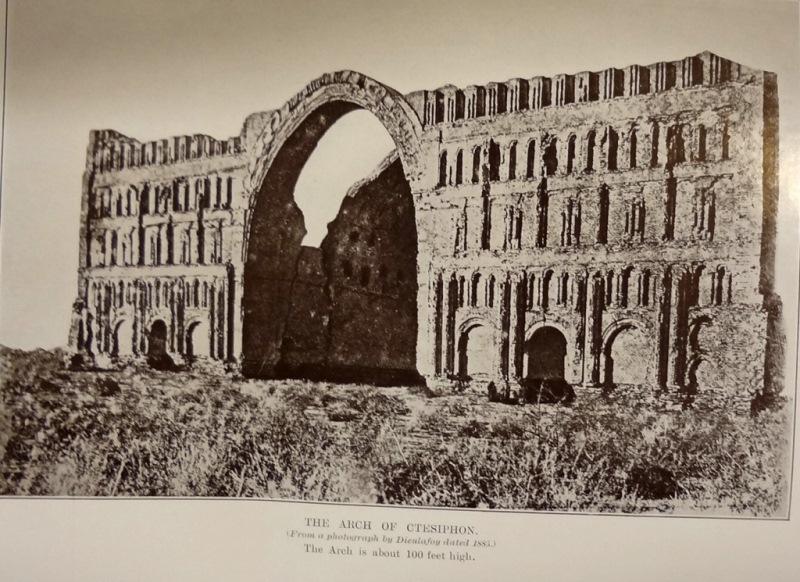

In January 1920, the Civil Commissioner in Baghdad had been warned that the Arch of Ctesiphon, some 22 miles south-east of the capital, was in a ‘dangerous state’ due to brick pillage. Temporary measures were taken, and the protection and repair of ancient monuments were factored into the budget of the Public Works Department in June, but a more consistent approach was needed. In July, the Foreign Office noted that ‘it [would] be a disaster if the great arch at Ctesiphon [collapsed]’ and that ‘this work must be treated priority’ (FO 371/5138).

The Arch of Ctesiphon (catalogue reference: FO 925/41384)

In April 1920, as the Treaty of Sèvres was still being negotiated with the Ottoman Empire, the Joint Archaeological Committee wrote to the India Office. They acknowledged all the efforts made by the military and civil authorities to safeguard antiquities and ancient monuments, but they wanted them to go further. They urged the formation of an efficient Department of Antiquities in Mesopotamia which would ‘allow the resumption of archaeological research under proper regulations’ (FO 371/5138).

All along 1920 and 1921, universities and museums applied to resume excavations. The British Museum, Oxford, Philadelphia, Chicago, Yale… all were anxious to start digging at the earliest possible date. Albert Tobias Clay, Professor of Assyriology and Babylonian Literature at Yale, also wanted to open a school and library for archaeological research in Baghdad. Writing to the Foreign Office, he advocated the creation of ‘an archaeological museum for the preservation and exhibition of the antiquities’ (FO 371/5138).

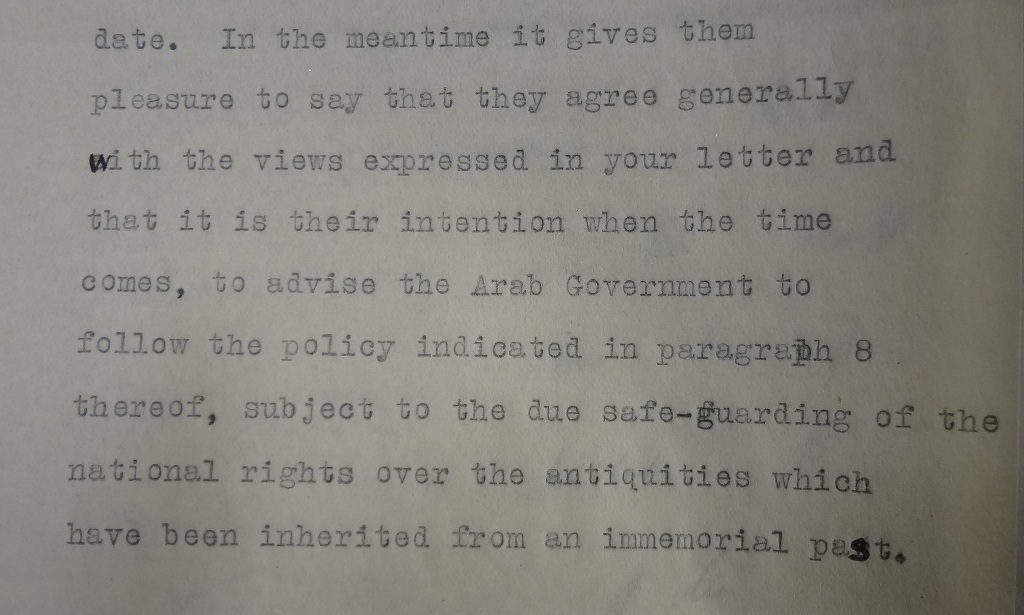

They all received the same reply. The authorities in charge were very much in favour of archaeological research and of ‘the due safeguarding of the national rights over the antiquities which [had] been inherited from an immemorial past’, but new excavations couldn’t possibly be permitted until adequate arrangements had been made for regulation and control. James Breasted, at the University of Chicago, was allowed to take an ‘archaeological expedition’ to Mesopotamia in February 1920 to inspect potential sites, but only because the letter of refusal took too long to arrive (FO 371/6362)!

India Office to University Museum, Philadelphia, August 1920 (catalogue reference: FO 371/5138)

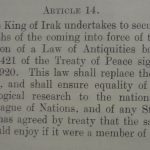

Aware that something had to be done, and given antiquities had been mentioned in the Treaty of Sèvres, the necessity of a Law of Antiquities was included in the Anglo-Iraq Treaty of 1922. Iraq had a year to ‘ensure the execution of a Law of Antiquities based on the rules annexed to article 421 of the Treaty of Peace signed at Sèvres’ (CO 730/167/1).

- Article 14 of the 1922 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty (catalogue reference: CO 730/167/1)

- Article 14 of the 1922 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty (catalogue reference: CO 730/25)

- Article 421 of the Treaty of Sèvres (catalogue reference: FO 93/110/81b)

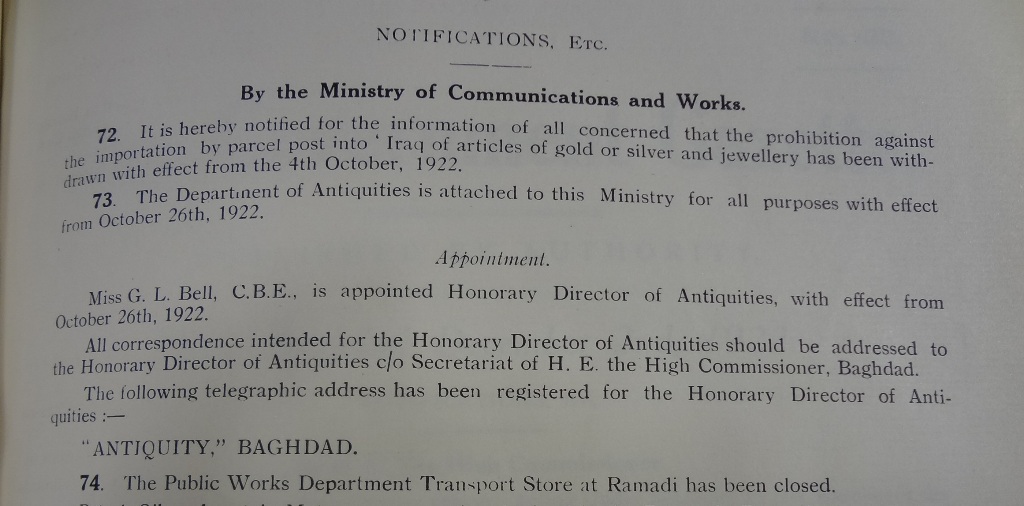

Shortly after the treaty was signed, a Department of Antiquities was created. At the request of King Faisal himself, Gertrude Bell, then Oriental Secretary, was appointed as Honorary Director. There wasn’t enough money for a fully equipped department, but it was a good start, and she immediately started drafting a new law (CO 813/1).

Gertrude Bell’s appointment in the Official Gazette (catalogue reference: CO 813/1)

Before the law was even passed, foreign expeditions were allowed back into Iraq. The British Museum started excavating in Ur in cooperation with the University of Pennsylvania; Oxford and Chicago joined forces at Kish. These two teams achieved tangible results very quickly, including (in Ur) ‘a headless statue of Ur Ungur of Lagash and a quantity of jewellery of the Achaemenid period’ (FO 371/10095).

Under the law as it still stood, half the objects found were to remain in Iraq. By 1923, antiquities starting piling up and something had to be done with them. Gertrude Bell managed to convince the administration to give her a room in one of the Government Offices. In the small, rather confined space, she laid out the Iraqi share of the Ur finds, each object carefully labelled in both English and Arabic. On the opening day, Leonard Woolley, the lead excavator at Ur, gave a very popular public lecture and, by all accounts, the day was a success (FO 371/10115).

The intelligence report for January 1924 described the main finds in great detail, and even the Foreign Office conceded: ‘the report on the excavations is very interesting’ (FO 371/10097).

The Law on Antiquities was finally passed in June 1924. Perhaps unsurprisingly, and in line with similar laws passed in neighbouring countries, it stated that the Iraqi government would be able to appoint representative to keep an eye on the excavators and that the Director of Antiquities could select whatever they wanted for the Iraq Museum. It was, however, very generous towards foreign archaeologists, allowing them to receive a substantial share of the artefacts uncovered and to export this share more easily than it had been under Ottoman law.

These very lenient dispositions made Iraq very attractive to foreign expeditions, and archaeology thrived in the 1920s.

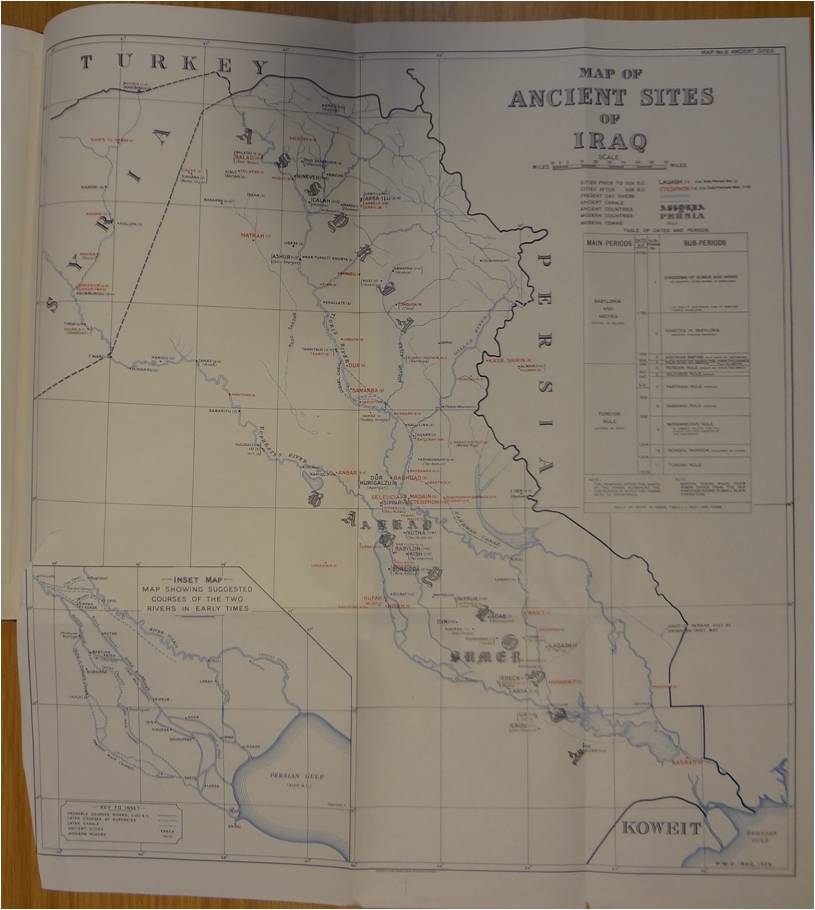

Map of ancient sites of Iraq (catalogue reference: FO 925/41384)

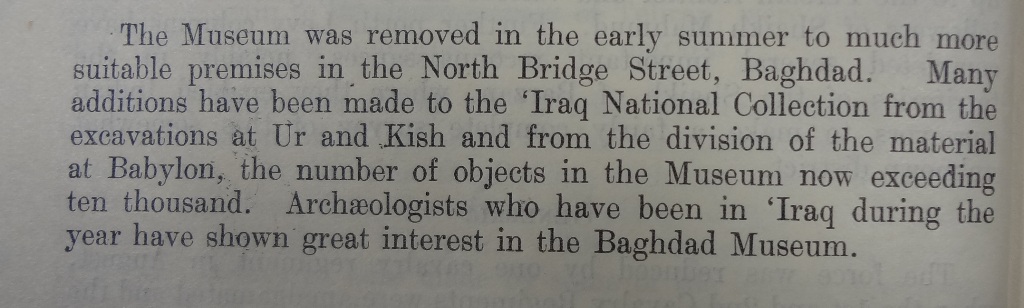

Overflowing with fantastic discoveries, the museum had to move to a bigger space, where the antiquities could be preserved properly. In 1926, Gertrude Bell, who had been looking for suitable spaces since the end of 1923, finally found the right place. Never one to exaggerate, she wrote to her mother: ‘it will be a real museum, rather like the British Museum only a little smaller’.

In June 1926, the museum moved to its new location in the North Bridge Street. To the objects found at Ur and Kish were added those which had been excavated by the Germans in Babylon before and during the war. Bell managed to persuade King Faisal to open the museum – or rather to open the one functioning room as the rest was still being built (CO 730/115/1).

A new location for the Museum (catalogue reference: CO 730/115/1)

Sadly, Gertrude Bell didn’t have much time to enjoy the result of her work: she died on 12 July 1926. The High Commissioner reporter ‘the grief which [swept] over the land at the news of her death’ (CO 819/2). The Report on the Administration of Iraq for 1926 noted that her early demise would leave in the Antiquities Department ‘a blank which it [would] be very difficult indeed to fill’ (CO 730/115/1).

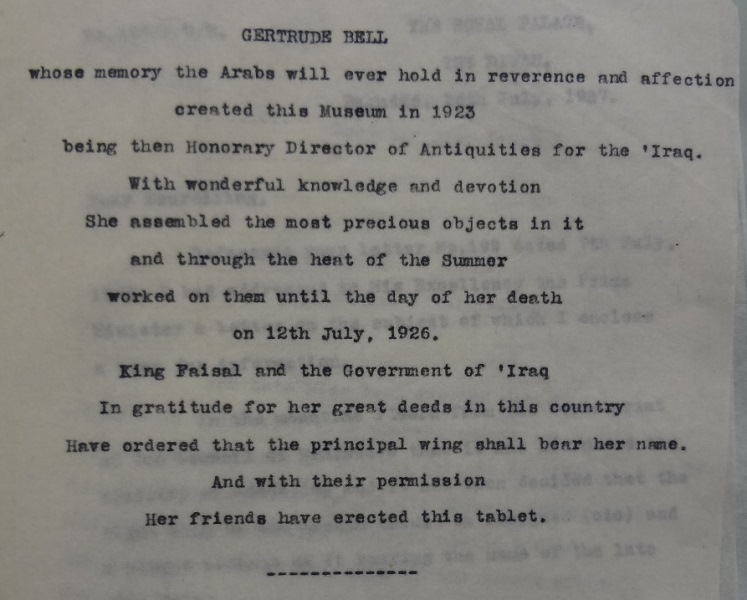

At King Faisal’s insistence, the right wing of the museum she had been so devoted to was named after her, and a brass plaque was unveiled in the summer of 1927, reading:

‘Gertrude Bell, whose memory the Arabs will ever hold in reverence and affection, created this museum in 1923 being then Honorary Director of Antiquities for the ‘Iraq. With wonderful knowledge and devotion, she assembled the most precious objects in it and through the heat of the summer worked on them until the day of her death on 12 July 1926.’ (CO 730/124/14)

Brass plaque in the memory of Gertrude Bell (catalogue reference: CO 730/124/4)

Since 1926, the Iraq Museum has changed a lot – except in spirit. Looted several times, it is still standing and aiming at protecting the archaeological heritage of Iraq from loss and destruction, just like the new Basra Museum. And, surely, this is a glimmer of hope at the terrifying time when large-scale looting and intentional destruction is leaving ‘a blank which it will be very difficult indeed to fill’.

Why is it rendered ‘Iraq in the documents?

Hi,

Thanks for reading the blog!

This is only the way in which the Colonial Office transcribed “العراق”, to acknowledge the ع sound…

On the spelling of Iraq and squabbles within British Government, see this: http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/call-lunacy/

Might the museum contain a copy of the Basrah Survey of 1914-15?

Hi Paul,

Thanks for reading!

We do have some maps produced by the Survey in series WO 302. The most comprehensive account of the survey and mapping operations in Mesopotamia can be found in Records of the Survey of India, vol XX: The War Record 1914-1920 published by the Survey of India in 1925. I hope this is helpful.

What a wonderful post, would be intrigued to see what other items you have relating to Gertrude Bell! What a woman!

Hi Hannah,

thanks for your kind comment!

We have a substantial amount of official correspondence from her time in the Arab Bureau and in Iraq, and her WW1 medal card… Feel free to come and explore!

Thanks for the important article.

As usually known, the first Iraqi law for antiquities was released by the efforts of Gertrude Bell in 1920s. But I see here there is a regulation issued in 1917 by Maude. What is the relationship between Maude and Gertrude? Where Maude did inspire his proclamation from?

Is there a clear image for his proclamation?

[…] Iraq National Library and Archive has seen plenty of turbulence since it was founded in 1920. But during the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 the library was burned and looted, losing 60% of […]

[…] Iraq National Library and Archive has seen plenty of turbulence since it was founded in 1920. But during the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 the library was burned and looted, losing 60% of […]

I enjoyed Dr Juliette Desplat’s article ‘The beginnings of the Iraq Museum’ published 15 November 2016.

I am wondering if she (or others) might know Gertrude Bell’s actual home address in Baghdad? The closest to the actual address was provided in an article by the archaeologist, M. E. L. Mallowan published in the journal of the British Institute for the Study of Iraq in 1976: ‘Iraq’ Vol 38, Issue 2, Autumn 1976, pp 81-84. In this he writes of his visit to her ‘little house behind what was then named New Street, Baghdad’.

I am undertaking research into Bell’s last few years in Iraq.

Did you make any progress on your search for the house? I am resident on Baghdad and a bit of a GB fan. Very curious to go and see the house