Many of our records are crucial to understanding the conflict for the crown throughout the ages, particularly key people and important events – battles, rebellions and dynastic change.

We are therefore delighted to be one of the main partners in a new exhibition – Battles and Dynasties – which brings together a diverse collection of internationally significant manuscripts, artwork and artefacts. 1 Jeff James, The National Archives’ Chief Executive and Keeper, is one of two Honorary Curators.

In this blog I will focus on the documents The National Archives is loaning to the exhibition, including Great Domesday Book, and the stories they bring to life.

The exhibition’s main focus is the second Battle of Lincoln, but it covers Lincolnshire’s role in historical events from 1066 to the present day. The battle was fought in the city on 20 May 1217. The army of Louis, son of the king of France, was defeated by the forces of nine-year-old Henry III (1216-72), led by William Marshal. This ended the threat of the English throne being united with the French in the person of Louis.

Seal of Nicola de la Haye (catalogue reference: DL 25/2890, (1215 x 1230), reproduced with permission from the Duchy of Lancaster)

One of the most important aspects of the battle is the role played by one of medieval England’s most remarkable woman, Nicola de la Haye. 2 Born to a local aristocratic family, she held the position of constable of Lincoln – one of very few women to hold royal office in this period.

Lincoln Castle, the seat of royal government in one of England’s largest shires, was first besieged by Louis’s army in the summer of 1216. It did not fall, due to Nicola’s actions.

She is depicted on a wax seal wearing a long-sleeved dress and holding a falcon, the symbol of her nobility. She used this seal to authenticate a grant of land. 3

Her resilient marshalling of the castle’s defence became imprinted on local memory. In 1279 jurors from the city, responding to an inquiry into landholding commissioned by Edward I, remembered a visit to Lincoln by King John in October 1216. Meeting John at the castle’s east gate Nicola offered him the keys saying:

‘she was a woman of great age and had sustained many labours and anxieties in the said castle and could no longer bear them. King J[ohn] replied sweetly “may you continue to sustain this burden, if it please you, and have custody of the castle for the rest of the king’s life”.’

Lincoln Hundred Roll inquiry, 1279 (catalogue reference: SC 5/LINCS/TOWER/17A, m. 1)

Nicola was relieved of custody of Lincoln Castle just four days after the battle; she was ordered to give up her office as sheriff of Lincolnshire at the request of the king’s uncle William Longespee, earl of Salisbury. But it was not an office Nicola would give up lightly: she travelled to London to petition the king and assert her rights. Henry looked favourably upon her due to her long service to himself and his father.

In an entry preserved on the 1217-18 Patent Roll (the record of letters issued by the royal Chancery and sent out to be publicly proclaimed) the king orders his uncle to restore to Nicola the castle and county of Lincoln. King Henry’s youth meant that the decision had probably been made with the agreement of his regent and mentor William Marshal, the earl of Pembroke. Marshal had been the other hero of Lincoln, leading his troops into battle despite being aged around 70. 4

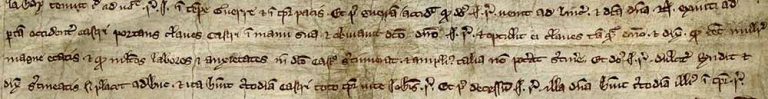

![The removal and restoration of Nicola de la Haye as constable of Lincoln Castle and sheriff of Lincolnshire, 32 [sic] October 1217](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/01150336/web-C66-18-m11r-crop-768x108.jpg)

The removal and restoration of Nicola de la Haye as constable of Lincoln Castle and sheriff of Lincolnshire, 32 [sic] October 1217 (catalogue reference: C 66/18, m.11)

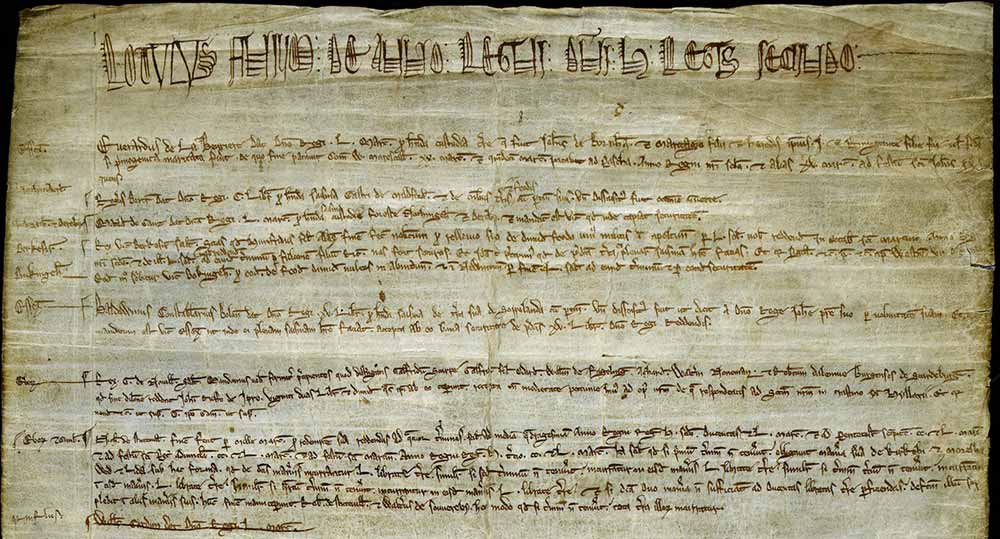

Ransom agreement between William Marshal and Nicholas de Stuteville, 1217 (catalogue reference: C 60/9, m.8)

Nicholas de Stuteville, one of the northern rebel barons, makes fine in 1,000 marks (£666 13s 4d) for his ransom. Not only would this have been an enormous sum to repay, penalty clauses were built into the agreement which stipulated the forfeiture of parcels of Nicholas’ manors of Kirkbymoorside (Yorkshire) and Liddel (Cumberland) should he fail to keep up payment.

The confident capitals at the head of this roll – ROLL OF FINES OF THE SECOND YEAR OF THE REIGN OF KING H[ENRY] – testify to the confidence at least one Chancery clerk felt in the settlement of his country brokered by William Marshal, and the preservation of the Plantagenet royal dynasty in the person of Henry III.

The Wars of the Roses

Government records only very rarely give us insights into the mind of individual monarchs at moments of crisis. One example comes from perhaps the most notorious period of dynastic conflict in English medieval history: The Wars of the Roses. The houses of Lancaster and York fought an often bloody conflict for the crown.

Warrant of Richard III concerning Buckingham’s rebellion, 12 October 1483 (catalogue reference: C 81/1392/6)

On 12 October 1483, while at Lincoln, King Richard III learned that Henry Stafford, duke of Buckingham, whom he had thought loyal, was involved in a rebellion against him. Richard scribbled a note on a warrant written to the chancellor, John Russell, to send the Great Seal to the king. He stressed that he wished:

‘to Resyste the malysse of hym that have best Cawse to be trewe the Duc of Bokyngham the most untrewe Creatur lyvyng.’ (to resist the malice of the man who has best reason to be loyal, the duke of Buckingham, the most disloyal creature living)

The immediate danger of revolt passed due to inclement weather and Buckingham’s failure to inspire support. He was ultimately betrayed and executed at Salisbury on 2 November.

Within 18 months Richard lost the crown to Henry Tudor, which ushered in perhaps England’s best-known royal dynasty. The reign of Henry’s son Henry VIII (1509-47) saw cataclysmic changes wrought to English society, as dynastic insecurity and political pragmatism fused with religious tensions to provoke the break of the English church and state from Rome.

The Lincolnshire rising

In 1535 commissioners were sent to value ecclesiastical properties and estates (documented in the Valor Ecclesiasticus, also on loan at Battles and Dynasties) and to investigate the moral propriety of the religious, at the behest of Thomas Cromwell, Vicegerent of the Church.

Cromwell began to suppress and dissolve monasteries. In Lincolnshire, general unrest combined with this religious dislocation sparked a popular revolt: the ‘Lincolnshire Rising’. Fearing an attack on parish churches and the loss of traditional practices and modes of belief, a mob clubbed the chancellor of the bishop of Lincoln to death at Horncastle on 1 October 1536. He had been inquiring into behaviour of parish clergy.

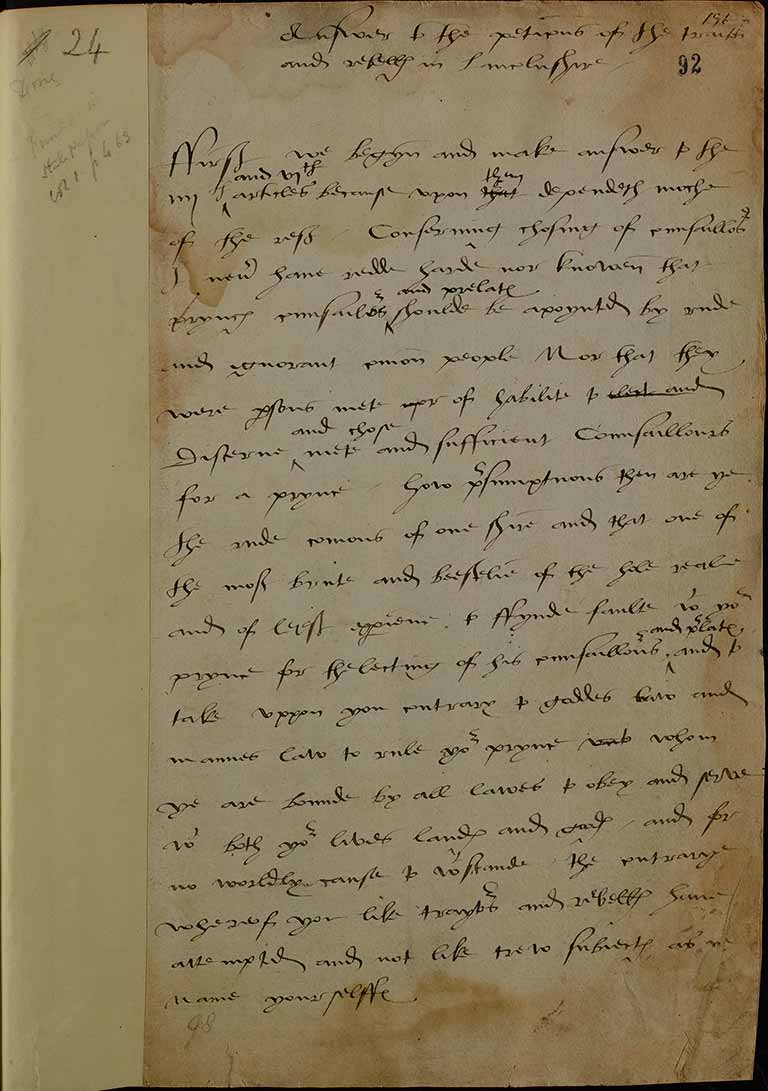

Henry VIII’s letter to the commons of Lincolnshire, October 1536 (catalogue reference: E 36/118, p.92)

Communities from across central Lincolnshire gathered in Lincoln; a letter of grievance was drafted and sent to the king.

Henry’s reply a week later contained a defiant statement which was read out in the Lincoln Cathedral Chapter House. It condemned the common people of the county for dictating to him how he should govern his realm:

‘I never have redde harde nor knowen that prynces counsailours and prelates shoulde be apoynted by rude and ignorant common people… How presumptuous then are ye, the rude comons of one shire and that one of the most brute and beestelie of the hole realme … to fynde faulte with your prynce.’ (I have never read or known the prince’s counsellors and prelates should be appointed by rude and ignorant common people. How presumptuous then are you, the rude commons of one shire, and that one of the most brute and beastly of the whole kingdom … to find fault with your prince.)

The obligations and privileges of monarchy were rarely so well defined.

Battles and Dynasties is an unmissable opportunity to see internationally significant objects, brought together for the first time, which contribute to the telling of the rich history of monarchy in Britain over almost ten centuries.

As a son of Lincoln myself, I am looking forward to seeing all of the treasures on display. Find out more about the exhibition.

Notes:

- 1. Battles and Dynasties is an exhibition developed by Lincolnshire County Council and Lord Patrick Cormack in partnership with the Historic Lincoln Trust, The National Archives and the British Library. ↩

- 2. L.J. Wilkinson, Women in Thirteenth-Century Lincolnshire (Woodbridge, 2007), ch. 1. See also http://magnacarta800th.com/schools/biographies/women-of-magna-carta/lady-nicholaa-de-la-haye/#_edn1. ↩

- 4. Full colour images of medieval seals in the Duchy of Lancaster series DL 25 and DL 27, with descriptions, can be downloaded for free from Discovery, The National Archives’ online catalogue. ↩

- 4. This is a story beautifully told in the Histoire Guillaume le Maréchal, which is also appearing in the Battles and Dynasties exhibition on loan from the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York (MS M.888). For William see Thomas Asbridge, The Greatest Knight: the Remarkable Life of William Marshal, the Power Behind Five English Thrones (London, 2015). ↩

[…] techadmin on May 9, 2017 Battles and Dynasties: a collaborative exhibition2017-05-09T13:50:30+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

[…] For more information about the exhibition have a look at these posts from the British Library, Historic Lincoln Trust and The National Archives. […]