This blog continues our series commemorating the centenary of the Battle of Arras.

The actual fight for the high ground of Vimy began in the half light of the morning of Monday 9 April, 1917. The morning began bitterly cold and overcast, something which may have helped the assaulting waves to make their positions without being noticed. Once there, they waited until precisely 05:30 when the bombardment began and the mines dug and laid by the engineers were blown.

Rising from their jumping-off points, the infantry pursued the barrage forwards towards the German lines. Protracted mining activity by both sides in the months before the operation had torn apart the ground into a chain of mine craters, which combined with the maze of shattered trenches and scattered wire entanglements, made early progress difficult for the Canadians. The inclement weather of the preceding days had also reduced the surface to a slippery quagmire, something made worse by deteriorating conditions on the ground. By 06:00, a north-westerly wind began blowing up snow and sleet which continued on and off for the rest of the day.

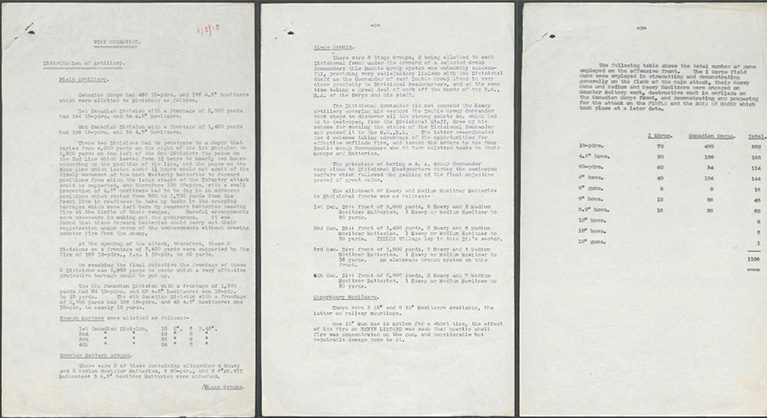

Distribution and organization of artillery for the attack on Vimy Ridge (The National Archives, catalogue reference: WO 95/168/9)

In spite of the conditions, at 07:10 the 3rd Canadian Division reported to Corps HQ that the whole of their Black Line – or primary – objective had been secured, and the same was confirmed by the 4th and 5th Brigades of 2nd Division at 07:20, and by 3rd Brigade of the 1st Division at 08:25. Events continued to develop rapidly – too rapidly for Corps HQ to keep up – and by 09:25, the 1st Division was reporting that it had secured all of its Red Line – or secondary – objectives and the 2nd Division reported the same soon after. The push on to their final objectives – the Blue and Brown lines – was met with remarkably little opposition, with the advance going according to programme; the battalions in the vanguard of both divisions marched on to the eastern slopes of the ridge and were the first Allied soldiers to look down on the Douai plain since the German reoccupation in 1915. By early afternoon, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd divisions were able to communicate the complete success of their operations.

Similarly favourable reports were initially received from the 4th Division, but as the morning wore on it became clear that elements of the German line were continuing to resist in its sector – potentially the result of a bypassed pocket of resistance. Elsewhere it was clear that the enemy had emerged from caves and tunnels once the attacking force had passed, re-occupying the line now behind them.

Canadians consolidating their positions on Vimy Ridge, April 1917 (Library and Archives Canada – MIKAN 3521877)

One area left in the enemy’s hands was Hill 145 – the highest and thus most significant portion of the ridge where the Canadian Expeditionary Force monument now stands – from which heavy fire was poured down on to the troops of the 4th Division to the right and left. The situation was made worse by a supporting position further north which was also still in German hands – the Pimple – from which enfilading fire was also being drawn. These significant points were held with great sacrifice and determination due to their significance to the German defence.

Despite energetic and courageous endeavour, these positions remained in the enemy’s hands into the afternoon when the decision was made to pause operations on these fronts. Despite these gaps in the advance, the ridge to a width of 7,000 yards and a maximum depth of 4,000 yards had been successfully captured, along with more than 3,000 prisoners and large quantities of artillery and military hardware. Though losses had been serious, this first day had undoubtedly been a success for the Canadians.

The counter-attacks expected during the night fortunately failed to materialise, providing some welcome respite to soldiers in the frontline. For the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Divisions, the work of consolidation progressed favourably; for the 4th Division, however, part of their main task remained unfinished. Early in the morning of Tuesday 10 April, the 10th Canadian Brigade received orders for the capture and consolidation of Hill 145, while during the day, the 11th Canadian Brigade were to push forward and establish themselves on the crest of the hill.

In the continuing snowstorms that swept the ridge, the 44th (Manitoba) and 50th (Calgary) battalions moved into position by 14:30, attacking with the barrage at 15:15 and storming the ridge. As the light faded, the only objective still not in Canadian hands was the Pimple. The attack had been costly, with the two battalions suffering more than 300 casualties, but they in turn had captured four machine guns, a trench mortar and 200 prisoners. The 4th Division had now completely captured all of its original primary objectives. All along the rest of the line the Canadian divisions had pushed out patrols to probe the enemy’s defences and had continued its work consolidating its own.

During the night and through Wednesday the consolidation and probing of the enemy line continued and orders for a general attack for the following day were issued to prevent the Germans from straightening their lines for defensive or counter-attacking purposes. Meanwhile, with observation posts now established along the whole of the ridge, the artillery was able to keep up vigorous harassing fire on the German forces, moving behind their lines and dispersing concentrations of soldiers. In view of the success on the Ridge and in order to press and exploit the advantage of his dominant position, the Corps commander – Lieutenant-General Julian Byng – then issued orders to 10th Brigade, 4th Canadian Division to push on with the attack on the last vestige of the German defensive line, the Pimple.

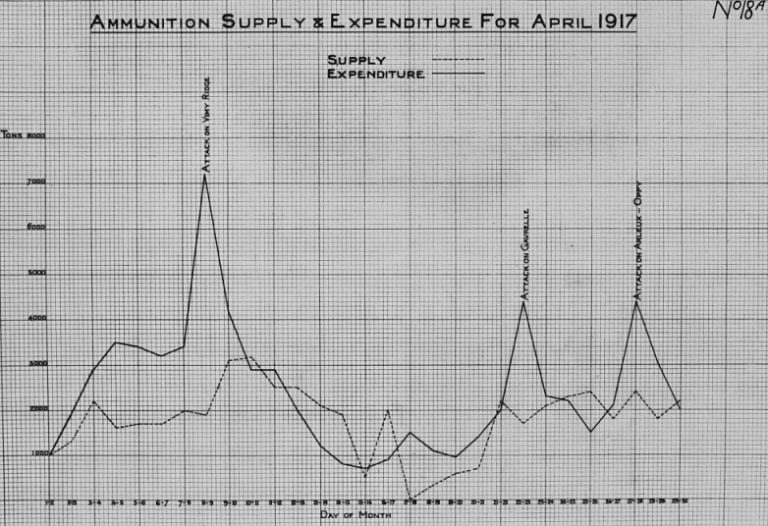

Graph showing First Army ammunition supply and expenditure in April 1917, with a substantial spike on 8-9 April annotated ‘Attack on Vimy Ridge’ (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 153/1284)

The Pimple had been a secondary objective for the original assault, but the necessary troops had not been available on the day and the attack had been postponed and made contingent on the success of the wider operation. Though not critical to the seizure of the Ridge, in German hands it had the potential to disrupt operations going forward.

A 05:00 on Thursday 12 April, after an intense artillery bombardment and under the cover of another rolling barrage, the 44th and 50th battalions – those who had so gallantly carried the line beyond Hill 145 the previous day – advanced on the Pimple. This formidable position was a maze of trenches and dugouts, but perhaps the greatest challenge was the steep sides and muddy ground – reported by the 50th Battalion to be waist deep in places – and the blinding snowstorm that met their advance.

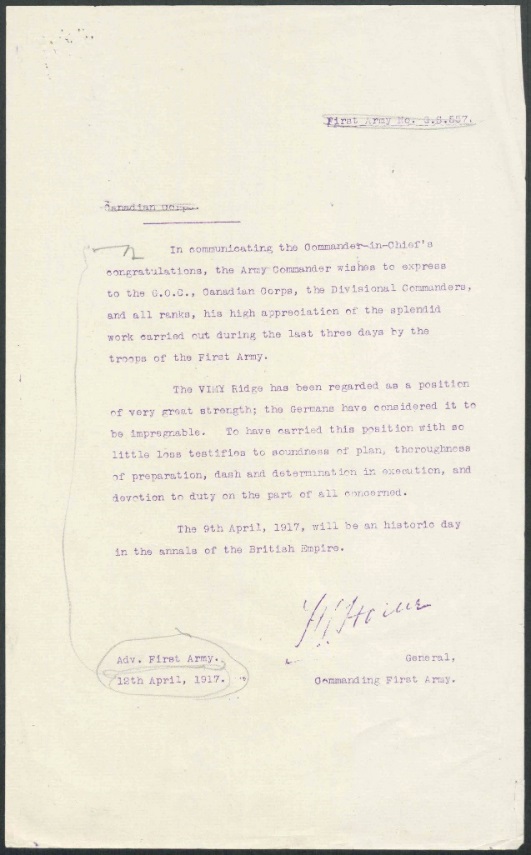

A message of congratulations from General Horne to the Canadian Corps for the capture of Vimy Ridge, April 12, 1917. (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 95/169/7)

Though unpleasant, the snow allowed the advance to close on the position to within 30 yards before the force was spotted, and though vicious hand-to-hand combat with the German garrison ensued in places, by just after 08:00 the Corps HQ was informed that the attacking battalions were on their objectives.

Though further operations were planned for the following day, the German command had already committed to retire and abandon the ridge and supporting positions, along with sizable quantities of materiel. As the report on operations written up for the Canadian Corps stated, ‘if Monday the 9th had been a great day of victory in battle, Friday the 13th was the day when the fruits of victory were enjoyed, for on that day the enemy accepted his defeat.’ The villages of Thelus, Farbus, Givenchy, Willerval, Vimy and La Chaudiere were in possession of the Canadians, along with Vimy Ridge, Hill 145 and the Pimple, and more than 4,000 prisoners had been captured as well as in excess of 60 guns and large numbers of machine guns, trench mortars and other arms. As the commanding officer of the First Army, General Henry Horne, noted:

‘The Vimy Ridge has been regarded as a position of very great strength; the Germans have considered it to be impregnable. To have carried this position with so little loss testifies to the soundness of plan, thoroughness of preparation, dash and determination in execution, and devotion to duty on the part of all concerned. The 9th April 1917, will be an historic day in the annals of the British Empire’.

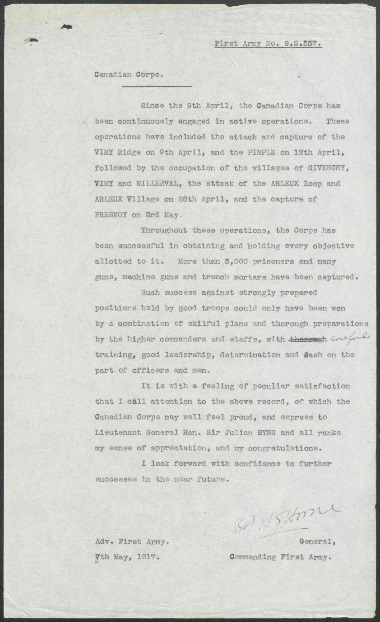

- A message of congratulations from General Horne to the Canadian Corps, May 8 1917, in recognition of their continuous engagement since 9 April. (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 95/169/7)

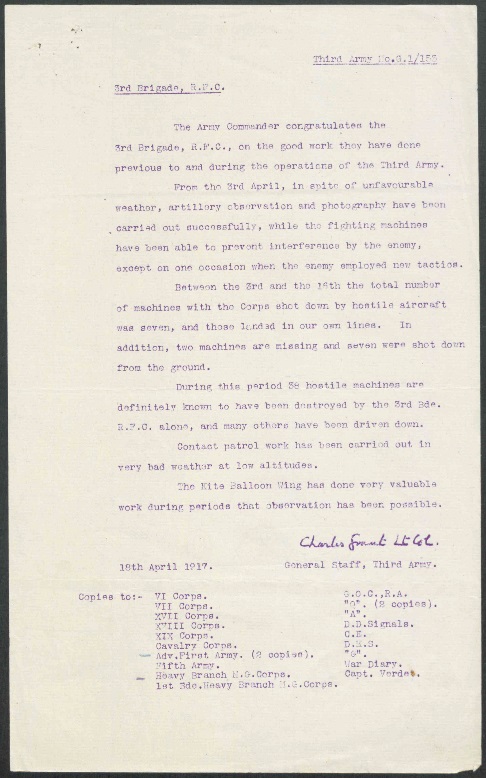

- A message of thanks to the Royal Flying Corps from Lieutenant-Colonel Grant, General Staff, Third Army, April 18 1917. (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 95/169/7)

This blog was developed under a collaborative agreement between Library and Archives Canada and The National Archives. Look out for the next blog in the series on 19 April.

As a Canadian citizen now living in and a citizen of the USA ,I am proud of the Canadians. I have been to the Vimy Memorial in France and was impressed. Also I have a 1st div helmet with the red patch of paint. Purchased at a gun show in Louisville KY