Illuminated image of a 15th century three-masted carrack (vessel of carvel planking and hull construction with high fore and aft platforms) in the Black Book of the Admiralty, dated 1450 (catalogue reference: HCA 12/1)

With the limelight of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt fading, the anniversary of a less well-known naval engagement fought in the mouth of the river Seine is approaching.

On 15 August 1416, a fleet of English ships under the command of the king Henry V’s brother the Duke of Bedford successfully defeated and scattered a Franco-Genoese naval force blockading the recently conquered port of Harfleur.

Also known as the naval battle of Harlfeur, one may question whether it is worth highlighting this relatively little known naval encounter at all, but there are two very good reasons for doing so.

Firstly, it was one of only a few naval battles fought by an English fleet in the medieval period. Secondly, without this victory Henry’s conquest of France from 1417-20 and the treaty of Troyes, agreeing to Henry inheriting the French throne, may not have happened.

Only half a year had passed since the victory at Agincourt, yet by April 1416, England’s hard won military prestige in 1415 was close to unravelling. French and Genoese ships had since raided ports and villages along the south coast of England and were besieging and blockading the port of Harfleur.

Described in a 1416 session of parliament as ‘the chief key to France’ (C 65/78 m.10, transcribed, translated and available online subject to subscription), Harfleur’s loss would be a huge military reversal for Henry damaging to both his military ambition and prestige.

Preparing the relief force

Sir John Skidmore and Reginald Courtoys, victualler, along with others, were dispatched from Harfleur to the king on 6 April 1416 to bring word of the increasingly desperate situation and gather much needed supplies and owed wages. Food stores were running low, the garrison had incurred losses in unsuccessful overland raids, and morale was lower still with wages outstanding. This must have caused alarm as a flurry of administrative activity followed a few days later to raise supplies and a relief force.

Entries in the enrolments of royal correspondence in the Patent and Close rolls (C66 and C 54) show that on 14 April royal officials were appointed to promptly gather supplies and oversee the requisitioning of ships for the relief of Harfleur. Richard Cliderawe and William Ledes were for instance ordered to buy 1000 quarters (that is 200 ‘tuns’ or 448,000 lbs) of wheat to be taken ‘with convenient speed for the victualling of the town of Harfleu[r]’ to the port of Sandwich (C 66/399 m.36).

Crews of merchant and fishing ships and privately owned vessels were obliged to perform service to the crown when required. These vessels requisitioned in English ports would serve alongside vessels directly owned or maintained by the crown. This was in effect England’s ‘Navy’ during the medieval period.

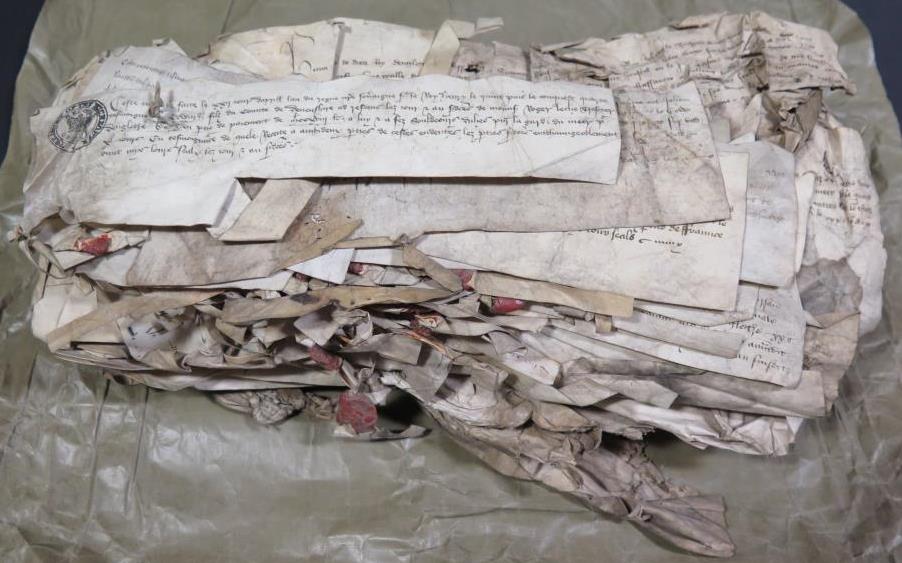

A bundle of indented contracts and warrants with masters of various ships and army retinue leaders serving in the summer of 1416 outlining length of service and payment of wages (catalogue reference: E 101/48/10)

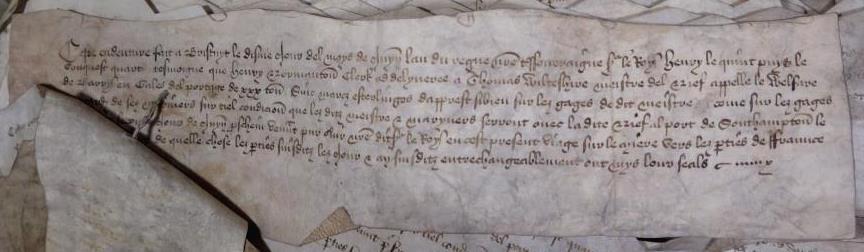

Indenture contract between the king and Thomas Wilshire, master of the ship called the Welfare of Barry, Wales for wages for himself and his mariners. He is required to rendezvous at the port of Southampton by 2 June 1416 (catalogue reference: E 101/48/10)

At the same time, preparations were being made to recruit soldiers to serve as the main fighting force on board ships to be assembled for embarkation at Southampton. There were no trained maritime fighting units like the Royal Marines on ships at this time, but mariners would have been involved in fighting if required.

Example of a one masted cog (vessel with wide and flat bottomed hull and high sides) on the mayoral seal for the port of Southampton from the early 15th century (Catalogue Reference: E 329/430)

French and Genoese ships attempted to frustrate efforts to relieve the beleaguered port by staging further raids on the south coast and blockading Portsmouth and Southampton in May 1416. English chroniclers even accused the French of entering into superficial peace negotiations to delay the dispatch of a relief force before the town capitulated.[ref]1. See ‘The Deeds of Henry V’, ed. and trans. F. Taylor and J. Roskell (Oxford, 1975), ch. 20, p.141[/ref]

These actions as well as contrary winds delayed the relief expedition by about two to three months, but finally two sections of the Duke of Bedford’s fleet set sail, arriving at the mouth of the Seine on 14 August.

The size of Bedford’s armada was perhaps between 250 and 300 vessels of varying tonnage. The smaller Franco-Genoese fleet, commanded by the Vicomte de Narbonne, consisted of approximately 100 vessels, eight hired Genoese carracks and 12 galleys. Although Bedford enjoyed numerical superiority, the Genoese carracks were formidable fighting ships, with high sides and larger in size than most vessels in the English fleet. Bedford’s task would be difficult.

The battle

As dawn broke over the waters of the Seine on 15 August 1416, the two opposing fleets taking advantage of the light winds closed in on each another.

The chronicler of the Deeds of Henry V picks up the story:

‘the two fleets…had drawn close to one another in the mouth of the river Seine and then having grappled, had come to grips, and…following an exchange of missiles, iron gads [sharpened spears], stones and other weapons of offence, the fury of the combatants had reached boiling point'[ref]2. Excerpt from ibid., ch. 21, p.147[/ref]

A French chronicler described the attempts of English ships to board the Genoese carracks with grapnels: they were repeatedly repulsed by a hail of missiles, spears and stones.

Contemporary representation of maritime warfare during the Hundred Years War. This image from the chronicles of Jean Froissart depicts a scene from the battle of La Rochelle, showing fighting between English and Spanish ships outside the French port (Source: Wikicommons)

The battle lasted for several hours but eventually the English triumphed, capturing three Genoese carracks and sinking one hulk. One further Genoese carrack was wrecked on a sand bank. The hard-won victory was made easier by the withdrawal of several Genoese galleys and other ships to the port of Honfleur across the Seine estuary.

Casualty figures for the battle vary between accounts. One states 1,500 French and Genoese dead, 400 taken prisoner and 100 English dead. One French writer states that at least 700 English knights and esquires were wounded during the battle.

Evidence of the damage done during the battle can be found hidden in the enrolled financial accounts of the exchequer. Inventories of the king’s ships enrolled in E 364 show certain equipment for two royal ships involved in the battle – the Holy Ghost and the Trinity Royal – that was lost, sunk at sea or damaged. Items include anchors, yard ropes lanterns and other apparatus.[ref]3. See I. Friel, ‘Henry V’s Navy: The Sea Road to Agincourt and Conquest: 1413-22’, (Stroud, 2015), p.123.[/ref]

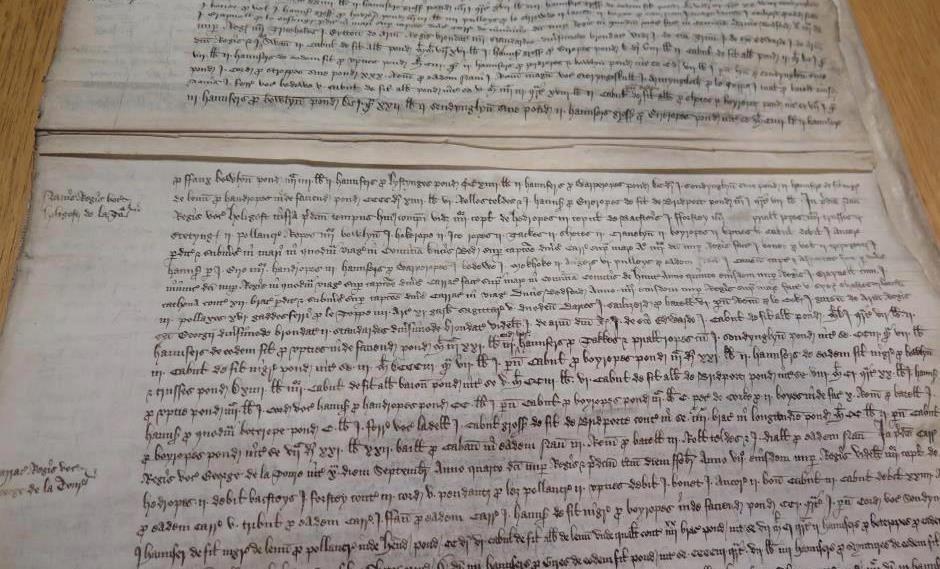

Entry in the enrolled foreign accounts of inventory of items for the king’s ship, The Holyghost (catalogue reference: E 364/59 Rot. J)

With the blockade now lifted, much needed supplies and reinforcements flowed into Harfleur. This remarkable victory alongside the tenacious defence by the garrison of Harfleur had prevented a catastrophic military defeat. It would herald the success of future English military operations in northern France.

Agincourt may have been a monumental victory against the odds, but it eclipses other military triumphs that were far more critical to the success of English military strategy in France in the 15th century. The battle of Harfleur is certainly one of these forgotten victories, and it deserves recognition for this very reason. Most importantly perhaps, the battle stands as a testament to the capability of England’s maritime forces several centuries before Britain established itself as a dominant naval power across the globe.

[…] techadmin on August 9, 2016 The Battle of the Seine: Henry V’s unknown naval triumph2016-08-09T11:22:21+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

I just wanted to correct a small mistake I spotted. The first image in the blog is of a three masted carrack ship rather than a two masted carrack ship as stated in the caption, however the foremast has no yard (beam horizontal to the sail) or sail visible but just a crows nest and rigging.

One further thing to correct is that the circular platforms at the top of the masts in the first image are called Top castles rather than crows nest as my previous comment suggested.

Shakespeare’s play

Henry 5th has the

Wonderful speech made by Henry to his troups before this battle of course that was the playwrights idea but it helps to describe the feeling of the men at that battle no