This blog post marks the centenary of the opening of the Battle of Amiens and continues our series exploring its impact on the final stages of the First World War.

Planning for the battle had been meticulous and secrecy had been stressed from the beginning in an effort to achieve surprise. This had stretched as far as withholding detailed information from soldiers until a day and a half before Zero Hour, and concealing the concentration of Allied forces in front of Amiens. This was to be a carefully orchestrated French and Commonwealth offensive, reliant on the close cooperation of infantry, tanks, artillery, cavalry and aircraft – all of which vastly outnumbered the forces they faced.

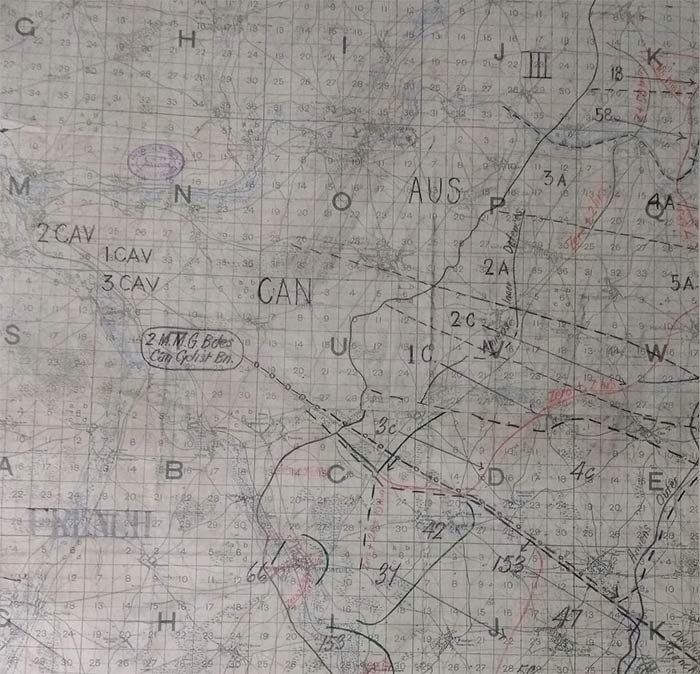

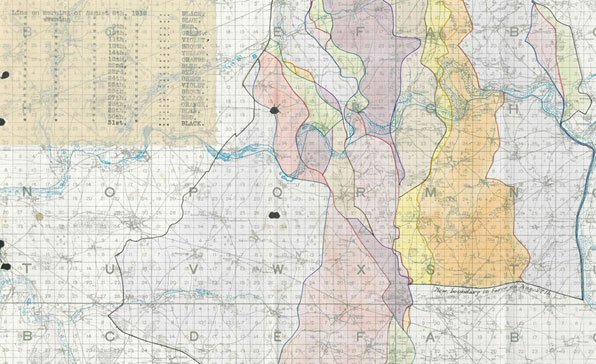

Prominent features of the battlefield included the Rivers Somme, Luce and Avre. High ground with wooded cover north of the Somme was more challenging, although south of the river the ground was flatter and more open. More significantly, beyond the German front line the ground was ideal for cavalry and tanks of all kinds. As with any planned offensive, a series of objectives had been selected, the greatest distance of which was a little over 12 km. The main thrust was to come from the Canadians and Australians in the centre, with British III Corps providing a defensive flank north of the River Somme. Divisions would attack the objectives in bounds, one passing through the other to continue the advance as the first secured the objectives behind.

Section of map outlining Allied objectives for Battle of Amiens. WO 153/310

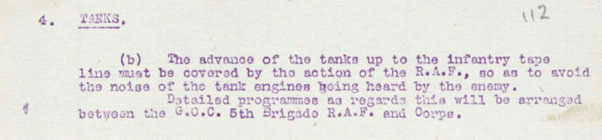

Zero Hour was 04:20, but most of the soldiers of the attacking force had crept forward to their jumping off points by 03:30. Guided through the darkness and obstacles by taped tracks laid by engineers, they waited silently under a fog that reduced visibility to ten yards in the Australian sector near the river. The mass of tanks that would provide the bulk of the firepower for their assault were also making their way forward, the rumble of their engines and the grinding of their tracks drowned out by a planned scheme of flying carried out by the RAF.

Instructions for the Amiens offensive, No. 32 (G), 31 July 1918. Fourth Army General Staff war diary (appendices), August 1918. WO 95/437/7

At 04:20 a crescendo of noise signalled Zero Hour. An intense barrage of high-explosive shells fell 200 yards in front of the jumping off points, while the tanks began moving through the infantry to lead the assault. There had been no preparatory bombardment, as it was hoped the firepower of the tanks and a rolling barrage in timed 100 yard ‘lifts’ would deliver surprise. Relying on compasses and good leadership to find their way forward, the bulk of the Commonwealth force found the going surprisingly easy, at least as far as the first objective.

Though some strongpoints provided stiffer resistance, most tank crews south of the Somme found German forces surrendered to their machines as they emerged out of the gloom. On balance, for the Canadians and Australians it was a day of overwhelming victory. Brigades of field artillery and contingents of Royal Engineers followed their advance in open warfare formation to provide support, while the cavalry, light Whippet tanks and armoured cars – as well as a battalion of Mark V* tanks (each transporting four fresh Vickers or Lewis gun crews) – waited to push through and test forward objectives.

The one major exception to this experience was north of the Somme on the Chippilly spur, where dugouts in the valley sides and the covered terrain allowed for a stouter defence. Holding up the attacking units of III Corps on their first objective allowed the defenders on the high ground to pour fire into the side of the Australian advance south of the Somme, something only overcome by the effective use of counter-battery fire.

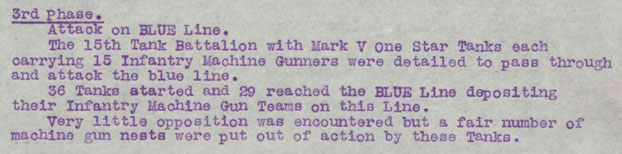

Having left British lines shortly before 04:30, much of the Allied attack had crashed through the first defensive lines by 07:30. This extraordinary success allowed the armoured cars and Whippet tanks to start harassing the retiring German forces and prevent them from rallying; the cavalry began securing prisoners and critical points ahead of the infantry (WO 95/1097/9). In the Australian sector, the novel Mark V* tanks which followed the cavalry were able to deliver their payload of machine gunners on to the final objective, securing it until the arrival of the 4th and 5th Australian Infantry Divisions.

5th Tank Brigade HQ War Diary, August 1918. WO 95/112/2

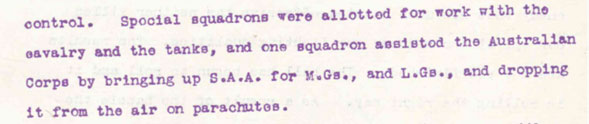

Alongside spotting for the artillery and patrolling the battlefield, the RAF also provided valuable close air support using machine guns and bombs, and even resupplied the Australian Corps by dropping ammunition by parachute.

Fourth Army General Staff war diary, August 1918. WO 95/434/1

Come mid-afternoon, the centre of the advance had driven forwards 12 km across a 22 km front. Though they lacked the advantages provided by tanks, the French had also made substantial gains in the south, finishing just shy of their final objective.

More limited attacks continued over the following days, including a succesful Anglo-American assault on the Chippilly spur, which brought Allied forces back on to the battlefields ravaged by the 1916 Somme campaign. Now overgrown and littered with blind trenches, shell holes and the detritus of war, the ground became difficult for the tanks and near impossible for the cavalry. With tank strength dwindling due to a combination of mechanical failures and losses, and the German army rallying behind a new line and threatening heavy losses to further major operations, the battle was shut down by Field Marshal Douglas Haig on 12 August.

The speed of advance had created new problems of coordination, particularly for the mechanised and horsed units that broke through to the rear. Communications with the RAF also broke down somewhat, with less being made of its tactical offensive capabilities than might have been. Anti-tank defences were better organised than expected in some areas given the level of surprise achieved, with tank battalions reporting use of mines, specially adapted artillery and obstacles. Despite these difficulties, General Erich Ludendorff reflected on 8 August as ‘the black day of the German Army in the history of this war’, largely because of the effect Allied successes had on morale. 1 The effect on Allied morale, however, was just as significant.

After a short pause, the British Third and Fourth Armies recommenced offensive operations further north, attacking over the Somme battlefields of 1916 and continuing a seemingly unstoppable advance that only ended with armistice. The Battle of Amiens marked the beginning of the end of the war on the Western Front.

Extent of advances both sides of the River Somme in August 1918. The enormous gains made by the Australians and Canadians can be seen in the colourless section in the bottom left. Fourth Army General Staff war diary, August 1918. WO 95/437/5.