The front cover of ‘Crucial Interventions’ Credit © Thames & Hudson 2015

Carianne Whitworth interviews author and medical historian Richard Barnett about bodies, the relationship between art and medicine, and archival love affairs.

CW: Hi Richard. Your new book ‘Crucial Interventions‘, an illustrated history of surgery, provides an illuminating context to some of the documents we hold here at The National Archives: from design patents for medical instruments to photographs of 19th century operating theatres. For those of us who are new to reading or researching histories of medicine, could you tell us about your experience of working with archives?

RB: Like most historians I served an apprenticeship in the archives: my PhD examined the emergence of obstetric anaesthesia as a clinical discipline under the early NHS, and I spent many happy early mornings cycling the Thames path to Kew, to go through the Ministry of Health and Central Midwives Board papers.

The things that really stuck in my memory were the little fortuitous discoveries – tracing a love affair between two civil servants through a series of pencilled notes at the bottom of carbon-copied letters, for instance.

Before that, I’d written a masters thesis based on the archive of the Society for Psychical Research at the University Library in Cambridge. I wanted to work out why psychical researchers had been so keen to connect their work with the networks of late Victorian science, and why they’d failed so completely. There’s one object in this archive – a small box, tied with a ribbon – which almost every researcher cannot resist ordering up because of its label: ‘Ectoplasm’ (to give the game away, it contains a piece of discoloured silk produced by the medium Helen Duncan at a seance in 1939).

An operating theatre at Guy’s Hospital in 1897 (catalogue reference: COPY 1/428)

CW: ‘Crucial Interventions’ contains fascinating but gruesome illustrations. Why do you think it’s important to engage with these images?

RB: These images can be very hard to look at – but it’s precisely their richness, depth and impact that makes them so powerful and so valuable. They remind historians that we must lift our noses from our texts and think about pictures and objects as historical sources. Most movingly, they bring us face to face, quite literally, with people whose names are not usually preserved in the historical record. They challenge us to tell the stories of poor patients, bodies on dissecting tables, and fragments of flesh preserved in formalin on the shelves of anatomical museums.

But I do think there are risks in using these images. They can give us the illusion that we’re somehow seeing the past unmediated, and this can be deeply misleading. Anyone looking at these images should be alive to what art historians call the ‘period eye’, and the different artistic and cultural and medical traditions these images embody.

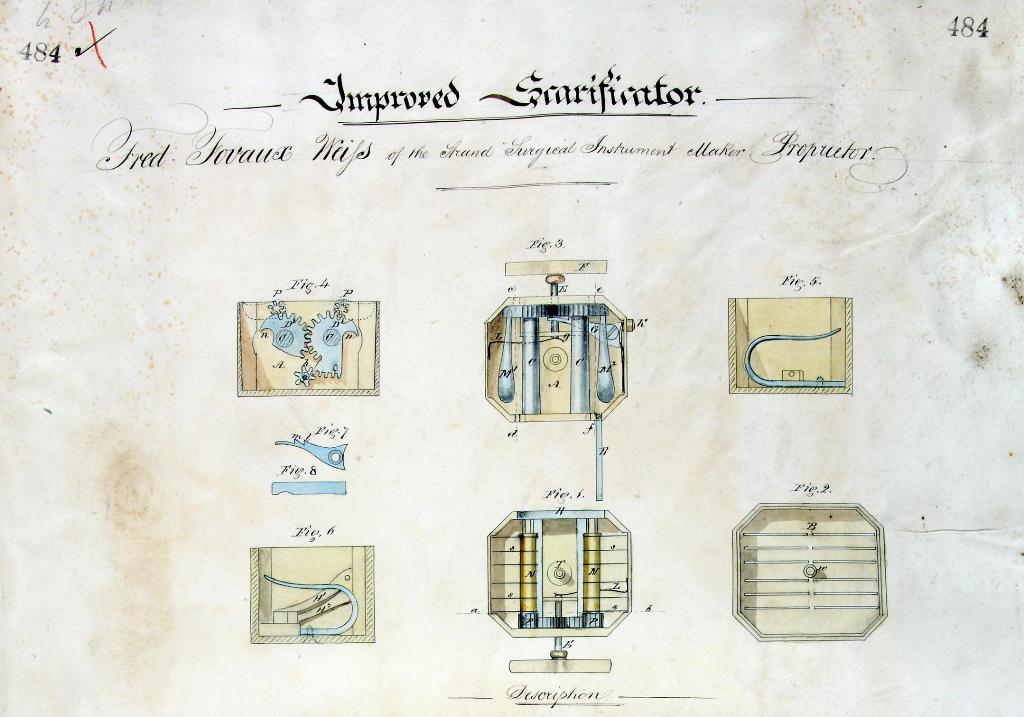

Part of a patent from 1845 for a scarificator, used for bloodletting (catalogue reference: BT45/3/484)

CW: Speaking of the ‘period eye’, do you think it’s possible that medical illustration could have informed figurative painting? I wonder also whether history can tell us much about the relationships between the medical illustrators and their patients?

RB: The illustrations in ‘Crucial Interventions’ remind us that there’s a long and fruitful history of collaboration between anatomists and artists. This makes perfect sense; after all, both disciplines share a set of concerns around the body, how it works and moves, and how to represent it convincingly on a page or a canvas. Most large art schools would have had visiting professors of anatomy and a room filled with skeletons and cast ecorches (bodies flayed to reveal the musculature). Sadly we know very few details of the relationship between particular artists and particular anatomists.

In a sense I think late 20th century art has felt the impact of medical illustration most deeply. Francis Bacon drew on anatomical and dental illustrations, and so many British artists since him – Damien Hirst, Marc Quinn, Anthony Gormley – have taken the body, especially the suffering, distorted body, as an emblem of our times.

The relationship between artist and patient is an intriguing aspect of the story of these images, the private moment at the heart of their creation. What (if any) kind of consent was involved? What did they talk about? Did the artist treat the patient as a still life, or as a suffering person? As medical historians and art historians continue to work on this subject I suspect more and more of these encounters will come to light. Wouldn’t it be a marvellous subject for a dramatist?

Richard Barnett will speak about ‘Crucial Interventions’ at The National Archives on 21 January 2016 at 6pm. The book combines beautiful and gruesome technical illustrations and paintings with fascinating essays on subjects such as anaesthesia, nursing and battlefield surgery. Find out more and book tickets.

Fascinating talk by Dr Barnett at The National Archives last night, which sadly felt somewhat undermined by the closure of the Bookshop one hour before the the talk commenced. While TNA have generally done an excellent job of promoting this event – with posters onsite, posts on social media, this blog, etc. – the Bookshop, the very place where you would expect to see ‘Writer of the Month’ events being promoted, appear to have done nothing whatsoever. Dr Barnett’s book hasn’t even been on display when I have popped in looking for it over the last two weeks (despite the online version of the Bookshop stating that it was ‘In Stock’). Two copies finally appeared next to the till yesterday afternoon.

If it is not possible for the Bookshop to remain open when ‘Writer of the Month’ events are taking place, can they at least make an effort to display the books which are being dicussed in the build up to the talks? Perhaps they could even ask the authors to sign a few copies to sell in the shop after the event has taken place.

Hi Mark,

I’m glad you enjoyed the talk, and thank you for taking the time to leave feedback.

Best,

Nell