After the First World War, the League of Nations granted France a Mandate on Syria and the Lebanon. If you have read some of my other blog posts, you won’t be surprised to hear that it led to archaeological issues.

By the 1930s, archaeology was thriving in Syria. Nationalism was growing in Iraq and many archaeologists relocated to the Sanjak of Alexandretta, in the northeast. They were well aware of the generous disposition of the Mandate towards foreign expeditions and took full advantage of it.

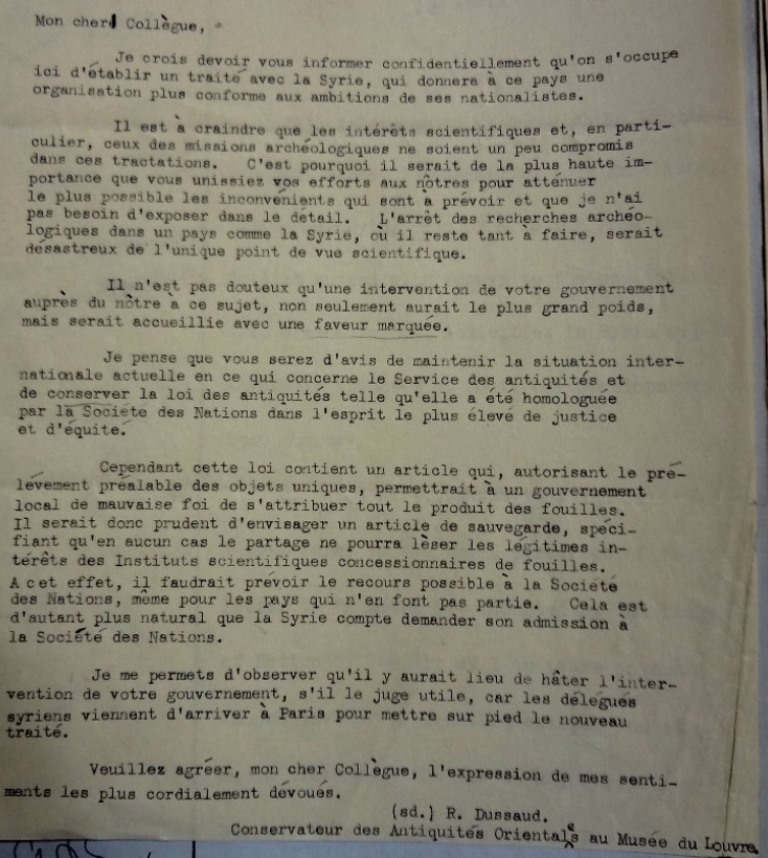

In 1936, René Dussaud, the Keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the Louvre, wrote to Sidney Smith, the Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum. He warned him that France was negotiating a Treaty of Independence with Syria and asked for British help to ensure that archaeological interests would be preserved. Syrian delegates had just arrived in Paris, he said, so time was of the essence. Dussaud assured Smith that a British intervention would be well received by the French authorities.

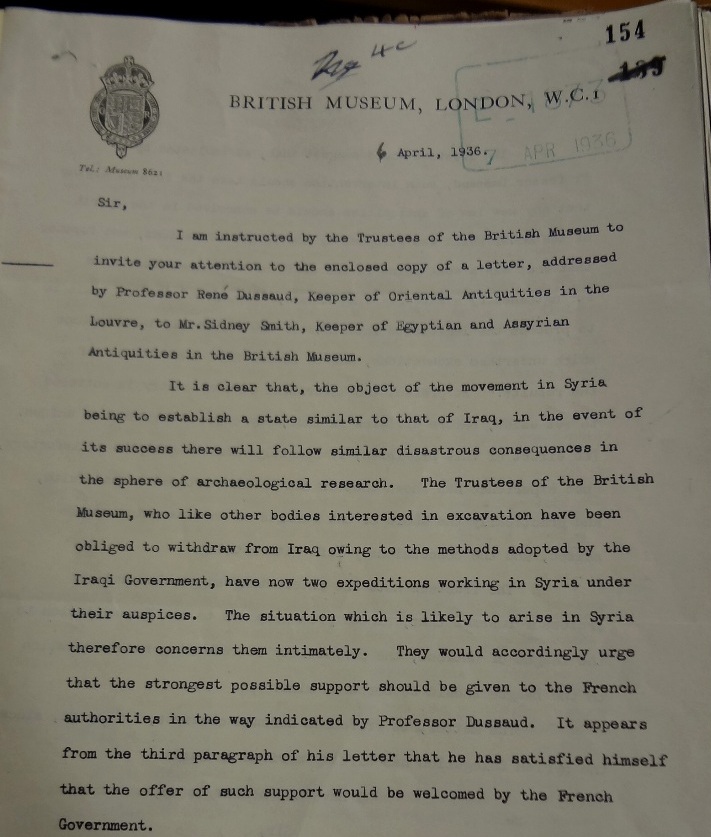

George Hill, the Director of the British Museum, promptly wrote to the Foreign Office, asking them to intervene. He was worried about the impact a national government in Syria would have on archaeology, especially when it came to the division of the antiquities discovered. He wanted a ‘safe-guarding clause’ to be included in the treaty, ‘to protect the legitimate interests of the scientific institutions which undertake excavations, and to secure fair distribution of the results’. He added:

‘It is clear that, the object of the movement in Syria being to establish a state similar to that of Iraq, in the event of its success there will follow similar disastrous consequences in the sphere of archaeological research.’ (FO 371/20065)

The Foreign Office were a bit sceptical. They didn’t think the French would welcome any intervention, especially a British one, and they felt that ‘it [was] hardly the moment in Syria to worry about archaeology’ (FO 371/20065).

Hill insisted that ‘the importance of Monsieur Dussaud’s assurances [had] been underestimated and that he would never say British intervention would be welcome if it wasn’t true’. The Foreign Office then started losing patience. In the Eastern Department, Ward was concerned that archaeologists could turn out to be as annoying in Syria as they had been in Iraq. He wrote:

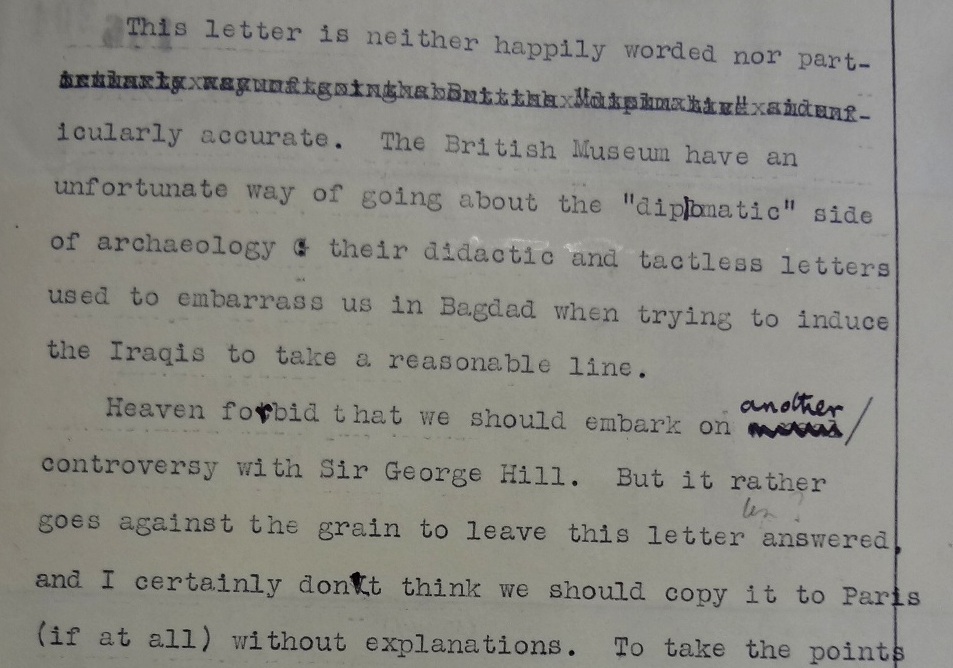

‘This letter is neither happily worded nor particularly accurate. The British Museum have an unfortunate way of going about the “diplomatic” side of archaeology, and their didactic and tactless letters used to embarrass us in Bagdad when trying to induce the Iraqis to take a reasonable line.’

Stephen Gaselee, the Foreign Office Librarian, added:

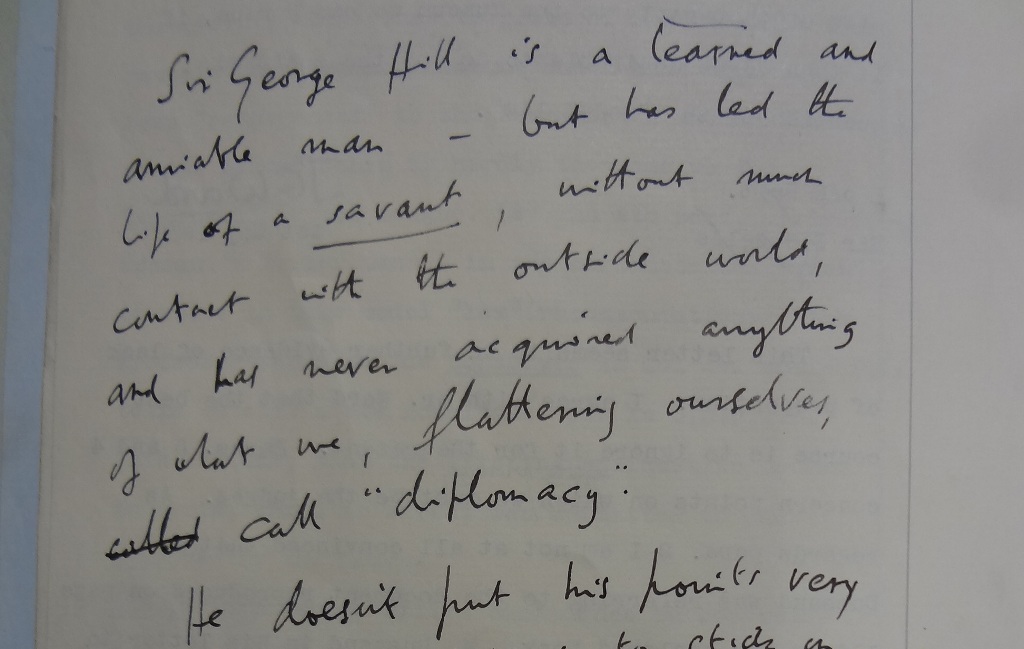

‘Sir George Hill is a learned and amiable man – but he has led the life of a savant, without much contact with the outside world, and has never acquired anything of what we, flattering ourselves, call diplomacy.’ (FO 371/20065).

On this occasion, however, the savant was right – the French reacted very favourably. They said they had intended to include an archaeological clause in the treaty with Syria, and that archaeologists would be consulted. ‘The task of negotiations’, they added, ‘would be greatly facilitated if [they] could point to the attitude of other Governments as supporting their own point of view’.

In the end, George Hill, René Dussaud and their fellow-archaeologists had worried for nothing. The French did sign a Treaty of Independence with Syria in 1936, but then refused to ratify it, and only left the country in 1946.

A whole new set of issues arose in 1939, especially in the Sanjak of Alexandretta, where the British Museum was digging. Turkey had always claimed the region as part of the ‘Hittite Biblical Kingdom of Anatolia’. Atatürk even gave it a new name: Hatay. On 3 July 1938, France and Turkey agreed that their armies would collaborate to defend the Hatay and maintain order. On 4 July, they signed a treaty of friendship and, on 5 July 1938, Turkish troops marched into the region. On 23 June 1939, following an agreement and exchanges of notes with France, the Hatay was annexed and became a Turkish province.

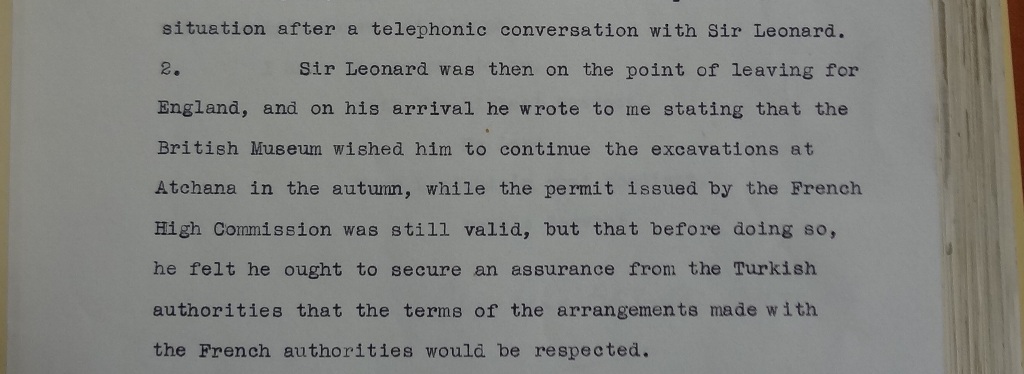

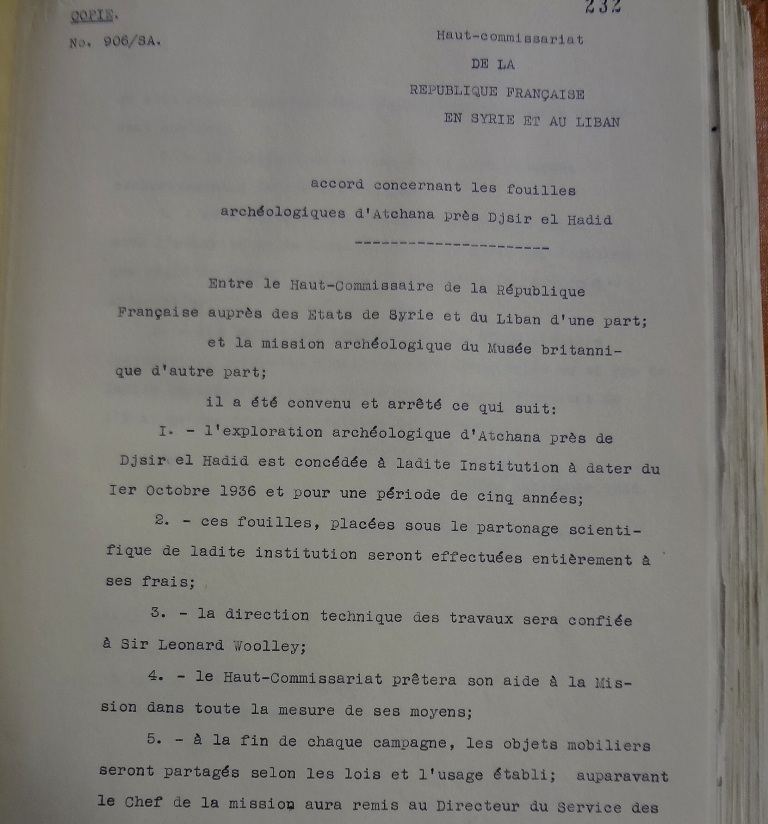

On 28 February 1939, as it was clear the Hatay would be fully handed over to Turkey, Leonard Woolley paid a visit to the Foreign Office. He had been digging in Tell Atchana, close to Antioch [Antakya], and he was concerned the new Turkish authorities might decide to change his contract and the way in which antiquities would be divided. He said he had been granted a three-year permit in 1936 and that, while the permit didn’t explicitly state he was entitled to half the objects, ‘this was provided by in the existing Syrian Antiquities Law’.

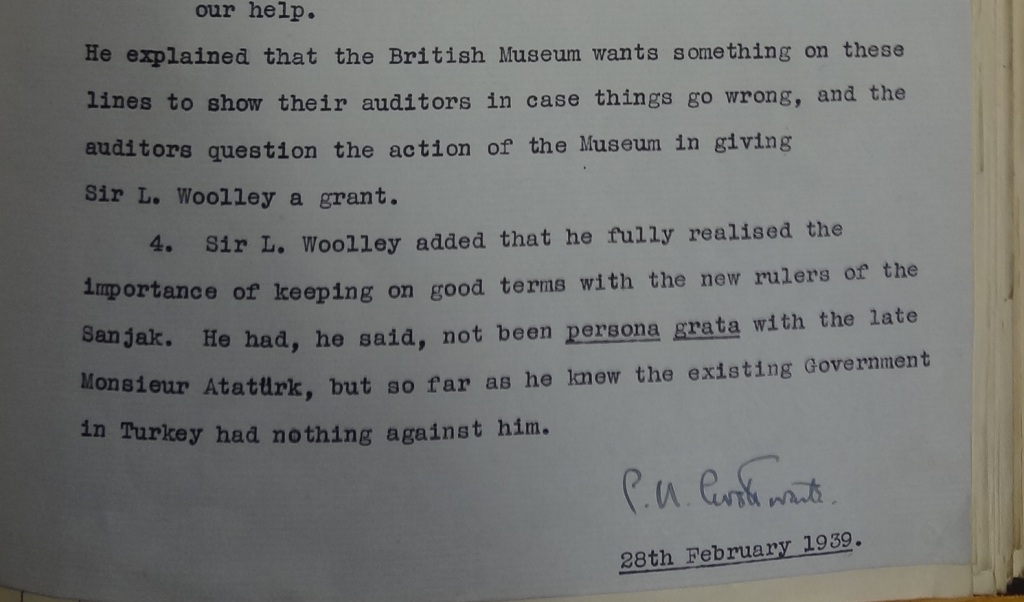

He asked the Foreign Office to provide him with a letter stating they had ‘no objection to his continuing his work in the Sanjak’ and that ‘if he [did] get into trouble through no fault of his own, [they] shall be prepared to give him [their] help’. He understood the importance of keeping on the right side of the Turkish Government and explained that he had ‘not been persona grata with the late Monsieur Atatürk, but so far as he knew the existing government in Turkey had nothing against him’ (FO 371/23280).

Crosthwaite’s report on a conversation with Woolley, 28 February 1939 (catalogue reference: FO 371/23280)

The Foreign Office granted his request ‘as long as he [realised] the need for not rubbing the Turks up the wrong way’. Woolley had not been on the best of terms with the Turkish government in the past. He was taken prisoner in 1915 after the siege of Kut, he claimed that the Turkish government allowed or even encouraged Turkish soldiers to use the reliefs at Carchemish for target practice, and was in return accused by the Turks of supporting Kurdish nationalists (FO 371/13822).

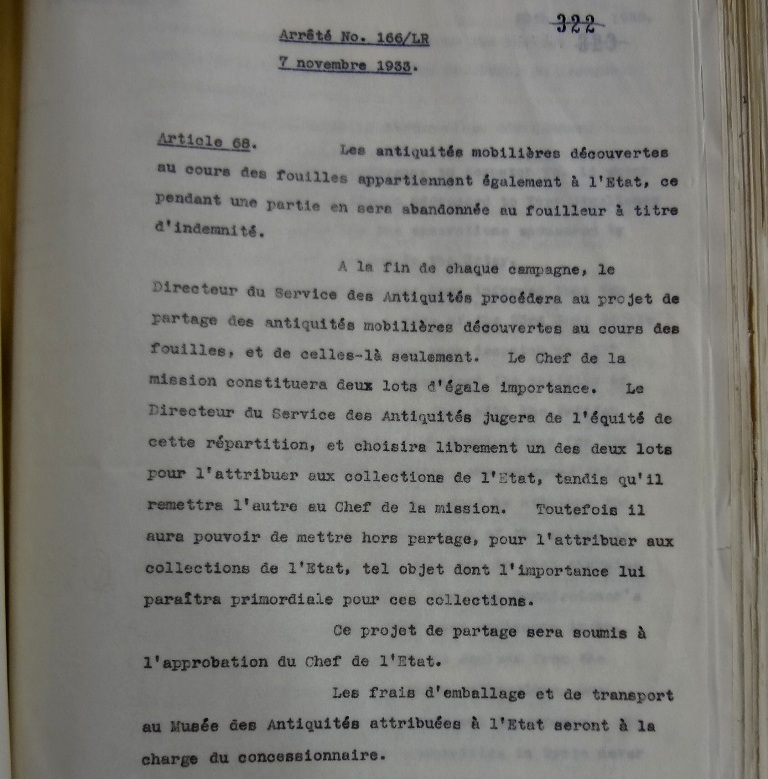

At the beginning of June 1939, Woolley had closed his dig. The Director of Antiquities at Antakya came to Tell Atchana to proceed to the division. According to Article 68 of the High Commissioner’s Decree of 7 November 1933, the excavators would, at the end of the season, divide all the antiquities into two lots of equal value and the Director of Antiquities would choose one for his Department. ‘Nonetheless, the Director of Antiquities shall have the right to select, prior to the division, any such objects as he shall think essential to the national collection.’ And that’s exactly what he did. He removed from the division a large statue, which had turned up almost on the last day.

Woolley protested, and pointed out that the French authorities in Syria had never applied that part of the law. The Director of Antiquities, ‘who’, the British Consul at Aleppo reported, ‘incidentally knew little or nothing about antiquities’, finally relented. On 5 June, however, the Hatay Council of Ministers, whose approval was needed to export the antiquities, decided that the statue must remain in the country.

On the following day, Woolley met with the President of the Council of Ministers, Abdürrahman Melek, and warned him that they risked putting foreign expeditions off digging in the region. He explained:

‘No European or American museum would work there if any first-class antiquity which turned up was to be automatically reserved for the Hatay Government and one half of second-class objects only would be left to excavators.’ (FO 371/23280)

Melek resubmitted the case to the Council of Ministers, to no avail. The Hatay authorities claimed they were taking ‘their orders from Angora [Ankara]’. Mehmet Cevat Açikalin, the Turkish Delegate in the Hatay, had to intervene, and Woolley was finally able to leave with his share of antiquities.

Later in the summer, Woolley, who assumed his permit was only valid until October, wrote again. He was anxious to conduct a last autumn season in the Hatay – and to ascertain that the terms of the 1936 contract would be respected.

The Foreign Office replied they were somewhat surprised because the exchange of notes between the French and Turkish Government in June 1939 regarding the settlement of the Hatay question had recognised the validity of the British Museum’s contract for five years, not three. As for the division of the finds, ‘a member of the French Embassy [in Ankara] expressed the opinion that if the 50-50 basis of partition [was] mentioned in the (…) contract, the Turkish Government [would] not alter it.’ (FO 371/23299)

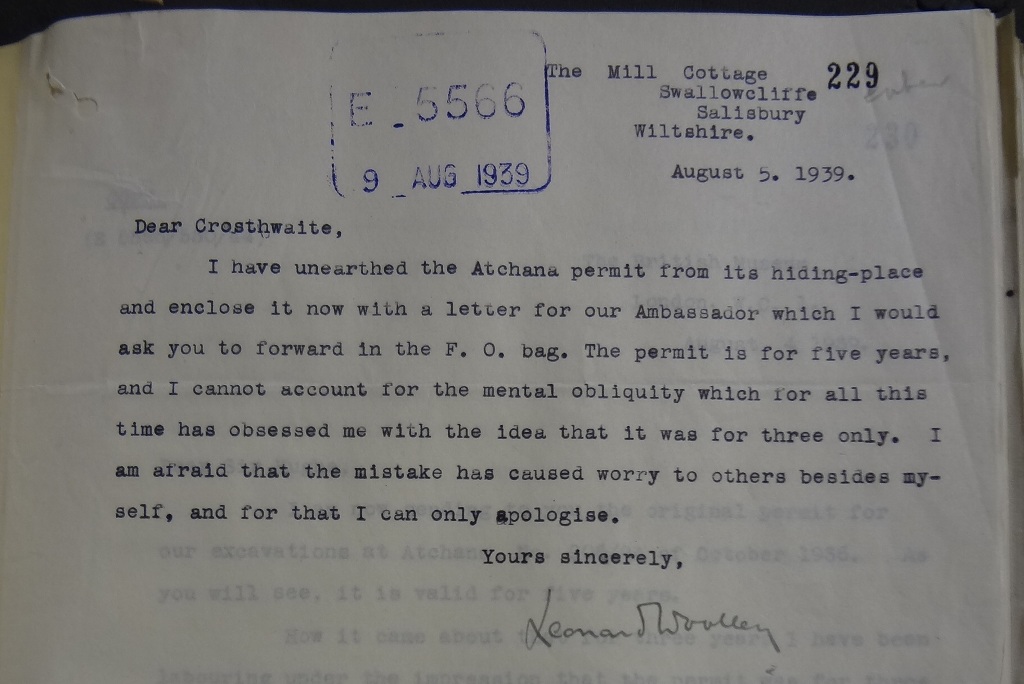

Woolley, who had said (rather forcefully) that time was of the essence as the permit was expiring in October, suddenly wasn’t sure whether he had been granted three or five years, and no one seemed to be able to locate the document. When the permit eventually turned up in August, Woolley realised that he had panicked for nothing and sent the Foreign Office a nice apology:

‘I have unearthed the Atchana permit (…). The permit is for five years, and I cannot account for the mental obliquity which for all this time has obsessed me with the idea that it was for three only.’ (FO 371/23299)

The British Museum then decided to cancel the autumn season and resume in the spring. They were still anxious to get confirmation the Turks would stick to the terms of the permit, which stated that at the end of each season the antiquities ‘would be divided according to the law and the established practice’. They though that, surely, ‘established practice’ (a 50-50 division) meant whatever law valid in the region before its incorporation into Turkey. They added that they would put an end to the excavations if it didn’t. (FO 371/23299)

Açikalin intervened again, and the British Museum finally got confirmation that the ‘established practice’ would be maintained until the end of the contract.

When the war broke out on 1 September 1939, putting an end to all excavations, Woolley at least went off with the comforting thought that, in the Hatay, it would be archaeological business as usual.

[…] Archaeological business as usual? Digging in the Hatay in the 1930s by Juliette Desplatt […]

Tthis post about the archaeological concerns in Syria during the 1930s brings to mind my own visit to the region last year. While exploring the ancient ruins, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of awe and gratitude for the preservation efforts made by archaeologists back then. It’s fascinating to see how their negotiations and interventions played a role in shaping the future of archaeological research in Syria.

Thank you for this informative article. My question is about details in the text.

Was it the French who established the law allowing for the sharing of the artifacts on a fifty-fifty basis before Hatay was liberated? The Ottoman Empire didn’t have such a law at that time.

Thank you in advance.

@Berna Güler you should check @HatayArkeolojisi page for more details