Last week marked the 500th anniversary of what is widely considered to be the starting point of the Protestant Reformation in Europe – the production of Martin Luther’s 95 theses in Wittenberg, Germany.

Martin Luther was an Augustinian friar who strongly disagreed with the Catholic Church’s practice of selling indulgences which claimed to reduce their purchasers’ time in purgatory after death. He wasn’t the first scholar to take issue with the practice, but his dispute led to a major upheaval – largely because he challenged the Pope in German rather than the Latin of traditional academic disputation, and because the relatively new invention of the printing press allowed his arguments to go viral across Europe.

Luther starts to feature in our records from 1518 onwards. A small selection of these records is currently on display in the Keeper’s Gallery here at Kew.

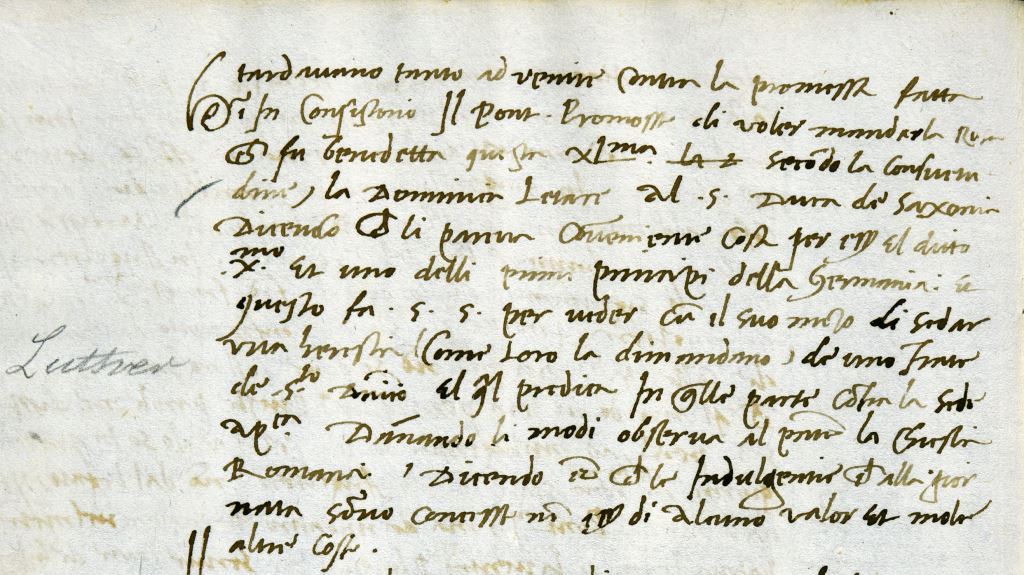

Entry in Marco Minio’s letter book referring to Luther with a 19th-century annotation in the margin, Italian (PRO 30/25/70)

The earliest reference we have to Luther appears in a letter book kept by Marco Minio, the Venetian ambassador to Rome. This isn’t a public record – it comes from a collection made by the antiquary, Rawdon Brown, who lived in Venice in the 19th century and edited the Calendar of State Papers Venetian.

On Brown’s death, he bequeathed some of his collection of papers to what was then known as the Public Record Office (now The National Archives).

Minio kept copies of the letters he sent to his employer, the Venetian Senate, in a notebook. In one, dated 4 September 1518, he made reference to the Duke of Saxony seeking ‘to allay a heresy (as they styled it) of a certain Dominican (sic) friar, who was preaching in those parts against the apostolic see, condemning the forms observed at present by the Church of Rome; alleging moreover that the indulgences daily conceded were of no value, and many other doctrines.’

The absence of Luther’s name, and the fact that Minio got Luther’s religious order wrong, shows that Luther was not yet as well-known as he would become in the following years.

The significance of the challenge that Luther posed becomes apparent in later records. An interesting cipher letter written in 1521 from the English ambassador to Cardinal Wolsey on the early stages of the Diet of Worms has been discussed in a previous blog. Another remarkable letter that we have in our collections is from Pope Leo X to Cardinal Wolsey from later in 1521, thanking him for his support against Luther.

Pope Leo X is probably most famous for granting indulgences in order to fund the reconstruction of St Peter’s Basilica; this was the very practice which was challenged by Luther’s 95 Theses. His Papal Bull of 1520, Exsurge Domine, contains a directive forbidding any use of Luther’s works.

Luther refused to recant and responded instead by composing polemical tracts lashing out at the papacy and by publicly burning a copy of the Bull on 10 December 1520. In his letter, Pope Leo X thanks Wolsey for his work defending the Catholic faith against the Lutheran threat and for forbidding the introduction of his books into England.

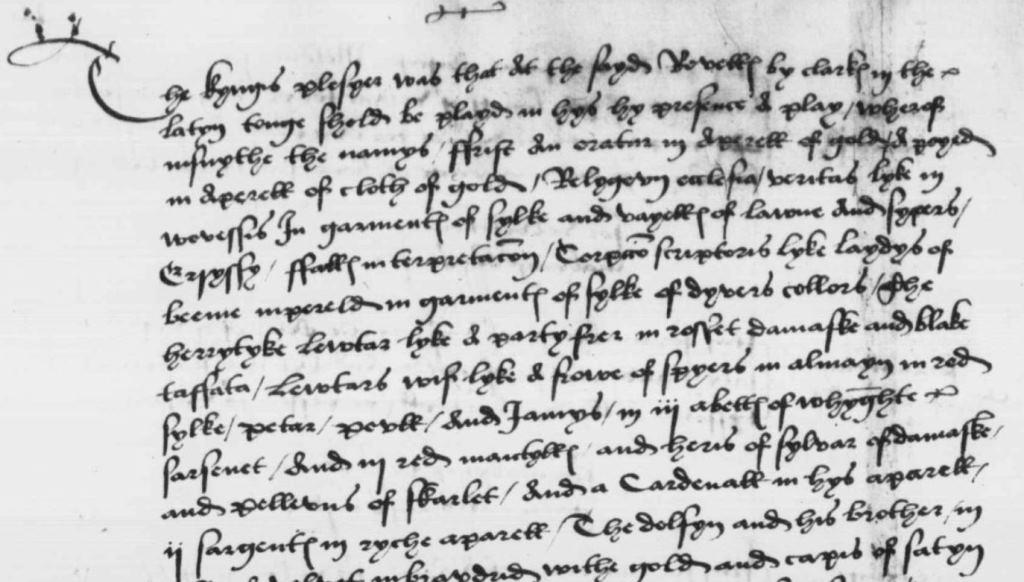

Extract from the accounts for the revels, 10 November 1527 (SP 1/45, f 36v)

Luther’s fame was well established by November 1527 when he and his wife were portrayed in a masque held at Greenwich in honour of the French ambassador.

At the orders of the King this was performed in Latin, and featured, among many other characters, players representing Religion, Ecclesia, Veritas, Heresy, False Interpretation and Corruptio Scriptoris, as well as ‘the heretic Luther, like a party friar, in russet damask and black taffeta [and] Luther’s wife like a frau of Speyer in Almayn [Germany], in red silk’. We think it is fair to assume that this portrayal of Luther would have been distinctly unflattering.

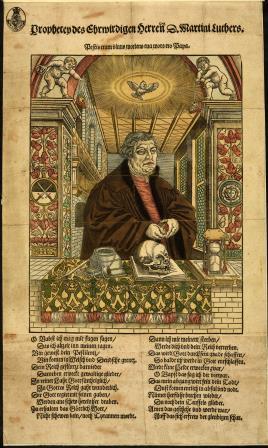

‘Prophecy of the Reverend Lord Doctor Martin Luther’, hand-coloured woodcut, 1546, Latin, High German (EXT 9/40)

Following Luther’s death in 1546, his supporters wanted to ensure that the legacy of Luther and his message would continue. One of the real treasures of our collections relating to the European Reformation is a hand-coloured woodcut of Luther, which is visually very impressive.

This woodcut shows Luther, along with a pen, ink pot, skull and egg timer, with some High German verses beneath. The title of the woodcut is in Latin and translates as ‘Prophecy of the Reverend Lord Doctor Martin Luther’, followed by a curious epigraph, also in Latin: ‘Pestis eram vivus, moriens tua mors ero, Papa’. This translates to ‘Living I was your plague; dying, I shall be your death, O Pope’.

Luther used woodcuts extensively to spread his message, as he believed that without images it was not possible to think or understand anything. So it seems fitting that he was commemorated in this format.

Prophecy was a genre of writing used by both Luther and his supporters as well as their Catholic opponents, to present the recent political past as an imagined future. It therefore acted as a form of political propaganda. 1

The purpose of this prophecy is to highlight the idea that Luther’s death would not mean the end of his message – his followers would grow in strength and the Pope and established Church should fear this. There appears to have been a resurgence of interest in prophecy after Luther’s death, so this might explain the appearance of pieces such as this woodcut.

By delving into the State Papers and related documents we can get a sense of how information ebbed and flowed across Europe and witness the thoughts of people caught up in the moment, little knowing how the impact of Luther’s Reformation would reverberate for centuries to come.

Notes:

- 1. See J. Green, Printing and Prophecy: Prognostication and Media Change 1450-1550 (Ann Arbor, 2012) ↩