Martin Scorsese’s recent cinematic epic Silence captures in vivid tones the intensity of persecution of Portuguese Jesuits and Japanese converts to Christianity in 17th century Japan. Although such a cinematic experience is intended to shock and provoke debate over faith, it also lifts the lid on a forgotten aspect of early modern history: when European trade and culture first made contact with the ancient kingdom of Japan.

For this reason I was intrigued as to whether The National Archives held any records shedding light on the dawn of Anglo-Japanese relations during the early 17th century.

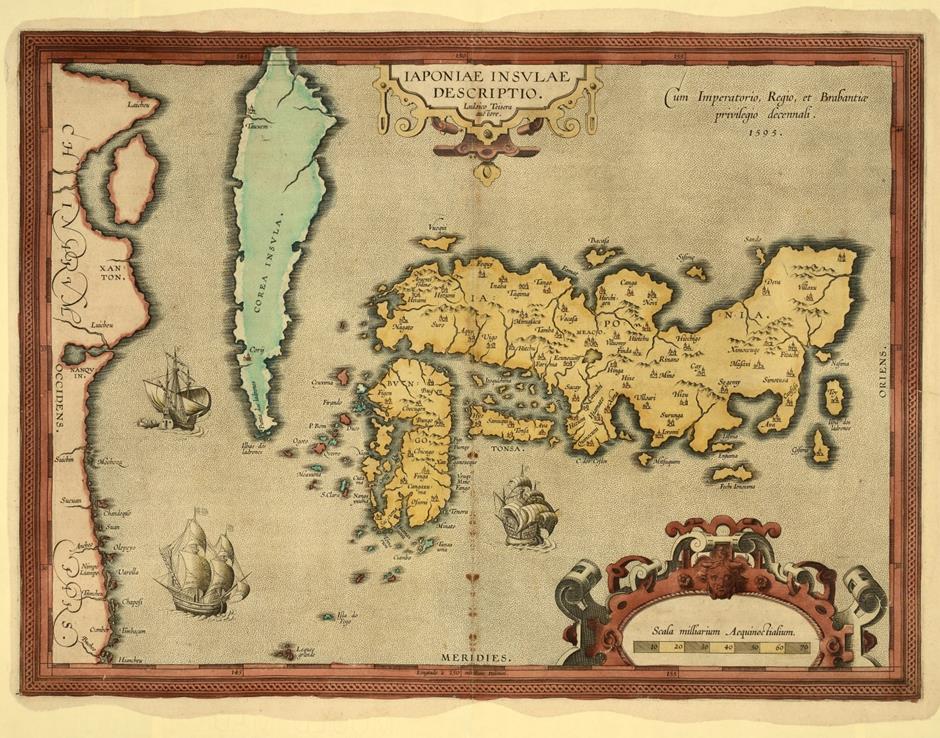

Map of Japan with Korea shown as an island and the coast of China, drawn by Portuguese cartographer Ludovico Teixeira alias Luis Teixeira , 1596 (Catalogue reference: MPI 1/409/6)

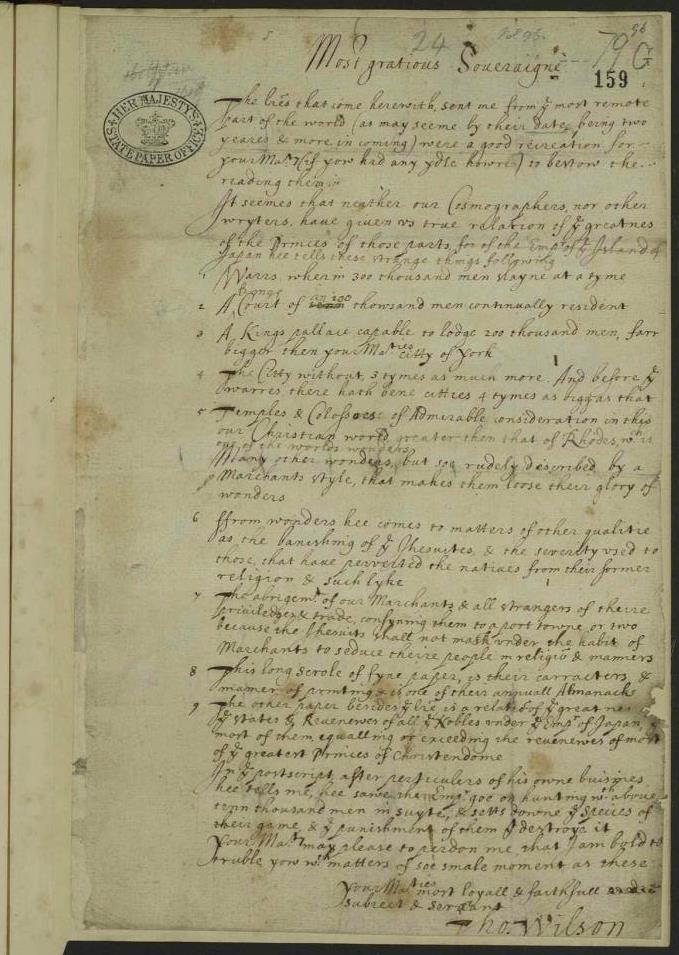

First letter from Sir Thomas Wilson to King James I regarding correspondence sent by Richard Cocks from Japan, March, 1617 (Catalogue reference: SP 14/96 f. 159)

A cursory investigation found some relevant information tucked away in the volumes of the State Papers records for James I. Most interesting are two letters from Sir Thomas Wilson, governor of the East India Company, to King James I, in which he summarizes the contents of letters dispatched to him from an agent in Japan two years earlier. These he encloses along with a survey of the states and revenues of Japanese nobles that apparently equalled or exceeded those of ‘most of the greatest princes of Christendome’, and a scroll containing a Japanese almanac (calendar) to the king for his recreational perusal.

In the first of these letters, dated sometime in March 1617, Wilson qualifies his actions by explaining that the little written and cosmographical material in existence were inadequate in giving ‘true relation of the greatnes of the princes of those parts for of the empire of the Island of Japan’.

He then summarises several fantastical observations made in the original letters by his agent, including ‘Warrs wherein 300 thousand men slayne at a tyme; A king’s court of an 100 thousand men continually resident’ and ‘A king’s pallace capable to lodge 200 thousand men, farr bigger than your majesties citty of York.’

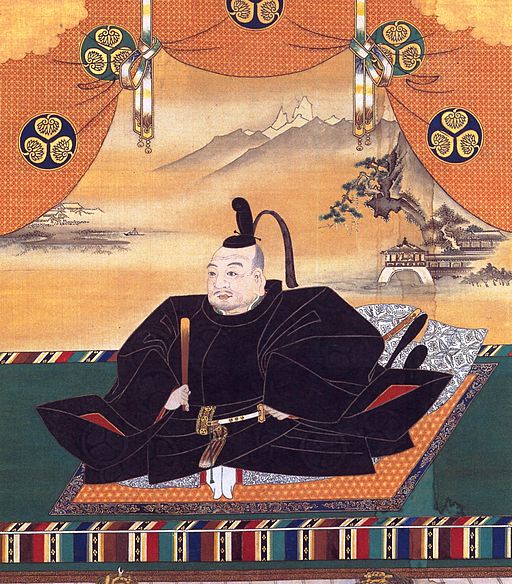

Emperor Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), Shogun from 1602-5 and Ogosho (retired Shogun) from 1605-1616 (Source: Wikicommons)

The agent in question, although not explicitly named, was Richard Cocks, chief factor and head of the English factory at Firando (Hirado), Japan. Cocks, who is likely Wilson’s patron, had sailed in the first English ship to reach Japanese shores in June 1613, the Clove, under captain John Saris. After Saris had left in December of the same year, he took over the role of negotiating trading privileges with the Tokogawa shogunate, and made frequent journeys to the court of Iyeasu Tokogawa and his successor Haditada at Suruga (Shidzouka) and Edo (Tokyo).

Many of Cocks’ observations on the outlandish and incredible facets of Japanese society relayed to the king via Wilson were scarcely believable to an English observer. Indeed Wilson’s second letter revealed that the king had dismissed them as ‘the loudest lyes’ he ever heard!

Yet it is unlikely that Cocks exaggerated what he saw, as his diary confirms. For instance, the claim that the king’s palace ‘capable to lodge 200 thousand men, farr bigger than your majesties citty of York’ is based on Cock’s observations of the king of Hirado’s castle, which he describes in his diary on a visit to the emperor’s court at Edo (Tokyo):

‘….from thence we went roundabout the kings castle or fortress, which I do hold to be much more in compass than the city of Coventry. It will contain 200 thousand soldiers in time of wars.'[ref]1. Diary of Richard Cocks, ed. Edward Thompson, Vol. 1, p. 172 (Hakluyt Society, vol. 66)[/ref]

In his second letter, Wilson reveals to the king that his ‘acquaintance, resyding at Edo’ had stated that temples he had visited contained between 3000 and 4000 golden idols. In his diary, Cocks describes his visit to the Temples at Miaco (Kyoto) on 2 November 1616, and the presence of 3333 brass images in one such temple ‘standing one foot upon steps, one behind another, one apart from another and over the great head with glories [of long brass rays], arms out of their sides and little heads out of the great’.

His entry for this day also describes the ‘huge collosso or brass image (or rather idol)’ of the Buddha reaching the height of the temple it was within, which Wilson’s letter makes reference to.[ref]2. Ibid., pp. 200-201[/ref]

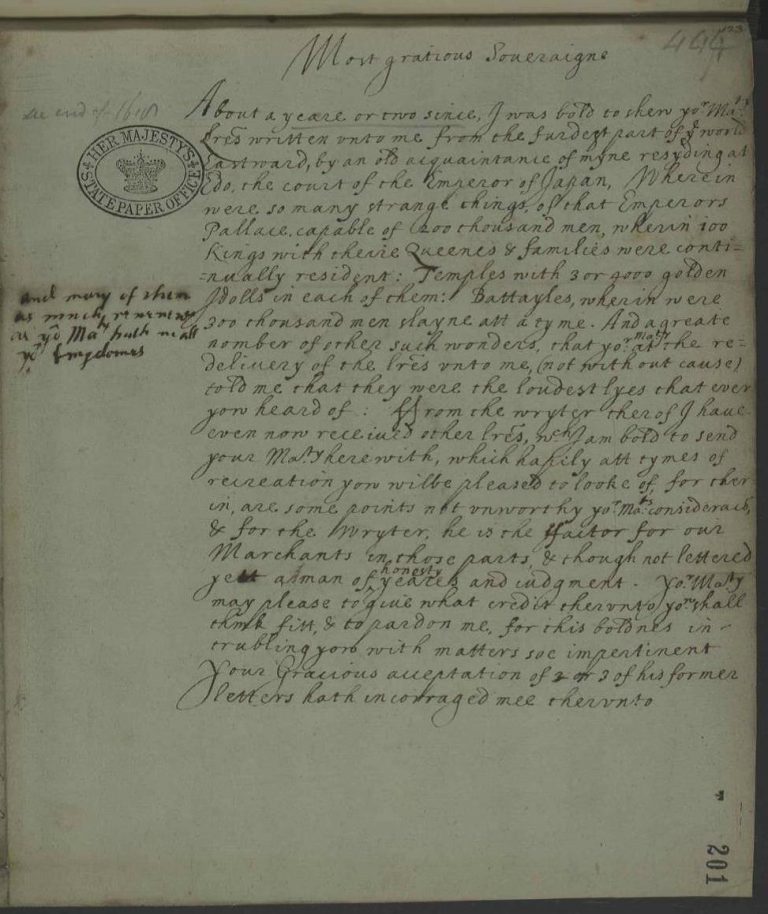

Second letter from Sir Thomas Wilson to King James I regarding correspondence sent by Richard Cocks from Japan, undated, 1619 (Catalogue reference: SP 14/111 f. 201)

In both his letters to the king, Wilson also mentions reports by his agent of the colossal size of the Emperor’s palace apparently ‘capable of [holding] 200 thousand men’. This ‘palace’ referred to was in fact Edo Castle which had an estimated circumference of between 6 and 10 miles and was divided into various wards. Other contemporary European eye witnesses also testified to the Palace’s vast capacity, such as the Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines, Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco, who described witnessing 20,000 servants and an armoury stockpiled with weaponry sufficient to arm 100,000 men.

A 17th century impression of Edo Castle and surrounding palaces from ‘View of Edo’ pair of six panel folding screens (Source: Wikicommons)

In his second letter Wilson adds that within the palace ‘100 kings with theire queens and families were continually resident’. This again was not embellishment but genuine observation made by Cocks of the Sankin-Kotai system, introduced by the Tokogawa Shogunate and designed to maintain imperial control over provincial lords or daimyos. This practice obligated the daimyos, or ‘kings’ as Wilson describes them, to live at the Emperor’s court every other year; their queen and heirs were to remain at the court indefinitely as guarantors for the daimyo’s loyalty. Residences were therefore established around the inner compounds of the castle for feudal lords, their wives and families.

Cocks may have exaggerated certain details and also overestimated the scale of what he was seeing because he was reliant on what he heard as well as what he saw. However, much of what he relayed was truth. Wilson himself testifies in his second letter that ‘though not lettered’, Cocks was a man ‘of honesty, years and judgement’. Yet to an English audience, including the king of England, such observations appeared too incredible to believe!

Wilson’s second letter above confirms that Cock’s original correspondence were returned to him by the king and therefore are unfortunately not preserved with Wilson’s own abstracts to the king in the State Papers. However both Richard Cocks’ correspondence with the East India Company from Japan and his personal diary can be found in the papers of the India Office collections at the British Library. Both been published by the Hakluyt Society.[ref]3. Diary of Richard Cocks, ed. Edward Thompson, 2 vols. (Hakluyt Society, 1883, vol. 66) which includes published correspondence in the appendices of vol. 2[/ref]