‘The Air Service is urgently in need of women workers – so urgently that every fit woman who is not already doing work of national importance should feel that a direct personal call has come to her.’

Women’s Work for the Royal Air Force pamphlet

![Women’s Work for the Royal Air Force pamphlet cover (catalogue reference: AIR 1/105/15/9/284)]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/01144802/Womens-Work-for-the-Royal-Air-Force-.jpg)

Women’s Work for the Royal Air Force pamphlet cover (catalogue reference: AIR 1/105/15/9/284)

On 1 April 1918, alongside the Royal Air Force, the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) was formed. Personnel of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and Women’s Royal Naval Service were given the choice of transferring to the new service and over 9,000 decided to join. Civilian enrolment swelled WRAF numbers. They were dispatched to RAF bases, initially in Britain, and then later to France and Germany in 1919.

Recruitment

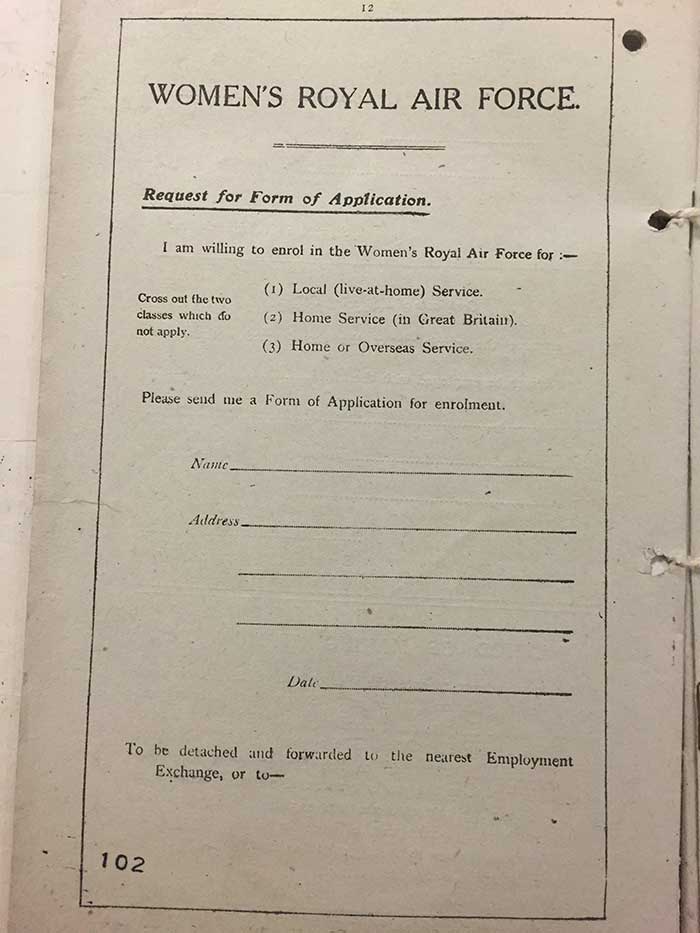

As with other services, the period of service was stated as 12 months, or for the duration of the war, whichever one turned out to be greater. Age restrictions were in place for candidates wishing to join. For overseas service, you had to be at least 20, and for home service, 18. Again, as with other female services, there were two categories: mobile and immobile. The former could work anywhere in Britain and were also eligible to be sent overseas; the latter would work locally. No member whose husband was serving overseas would be eligible to serve in the same theatre of war as he did. If the husband was subsequently ordered to the same theatre of war, then the WRAF member would be withdrawn from that area and sent elsewhere.

There were certain occupations where, if the woman was already employed in one of these, she would not be allowed to serve in the WRAF unless she brought a letter from her employer stating that she had permission to do so. Some of the occupations that came under this restriction were: school teaching; work in VAD, military, Red Cross and civilian hospitals; munitions work; and government service. There were also restrictions relating to the nationality of the woman (or of her parents or husband). Candidates, unsurprisingly, had to be medically fit and undertake medical examinations. And finally, one of my favourite parts of enrolment into women’s services: they had to provide two references, one of which had to come from another woman.

Request for form of application (catalogue reference: AIR 1/106/15/9/284)

Different roles

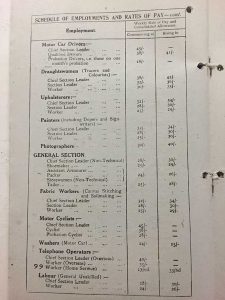

The Conditions of Service for the Immobile Branch (those who would stay at home and work in an area they lived in or near – essentially, local service) states that ‘women are urgently needed to release fit men for active service’, which was a common line used in the recruitment for all the women’s services in the First World War. These women were required for various branches of technical work on airplanes, and as motor drivers and cyclists. Apparently no woman should feel that this service was not for her due to lack of skills in these areas – training would be provided. During this period they would be paid learners’ rates. Women were also required as cooks and waitresses, and for household duties in the messes.

- Schedule of employments and rates of pay (catalogue reference: AIR 1/106/15/9/284)

- Schedule of employments and rates of pay (catalogue reference: AIR 1/106/15/9/284)

The areas of work that could be undertaken were split into four categories:

- clerical

- household

- general

- technical

The clerical section included clerks, shorthand writers and typists. Cooks, waitresses, laundresses and domestic workers came under the household section. The general section included storehouse women, tailors, shoemakers, telephonists and motor cyclists. And finally, the technical section encompassed jobs such as motor car drivers, photographers, fitters, metal workers, aeroplane riggers, wireless mechanics, and so many more.

Disbanded

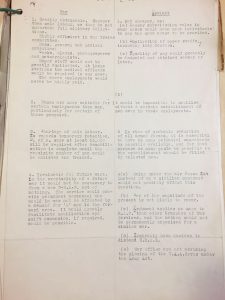

At the end of the war, a lot of debate seemed to surround what should happen to the WRAF and whether or not it was worth keeping some women in employment at air bases.

- Pros and cons lists for employing women in the air force (catalogue reference: AIR 8/1741)

- Pros and cons lists for employing women in the air force (catalogue reference: AIR 8/1741)

In 1919, there was a lot of argument within the air ministry about the future of the WRAF. In October 1919, Trenchard argued the following:

‘It is absolutely necessary to retain a certain number of W.R.A.F.s for Cooks in hospitals. The Doctors are insistent that they must be under some sort of discipline, and though we are trying to train Cooks it is not easy to do in so short a period. Therefore I wish for sanction to keep up to 300 W.R.A.F.s as cooks or clerks until at least April 1st, 1920.

However earlier in the year, arguments such as the following were made for keeping women around:

‘My reasons for advocating a permanent W.R.A.F., are:-

1. They are generally speaking, highly efficient, if perhaps, a little more expensive than man power.

2. In the event of mobilization, the employment of women on a large scale will be required, and we shall have a nucleus of a highly efficient and well trained organization on which to expand.

3. At large establishments I think that they tend to improve the general welfare of the men, in the matter of dancing and concerts etc., more especially in the big establishments which are situated at some distance from a town.’

Despite these arguments, the WRAF were disbanded in 1920, although with the outbreak of the Second World War, the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) was founded.

Research at The National Archives

We have service records for around 30,000 women who served in the WRAF between 1918 and 1920. Find a research guide on how to navigate these.

Information that can be found on these records can include any of the following:

- age

- address

- religion

- marital status

- dependants

- details of next of kin

- statement of services and promotions

- transfers

- trade or profession

- physical description

- discharge details

[…] http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/100-years-since-formation-of-womens-royal-air-force/ […]